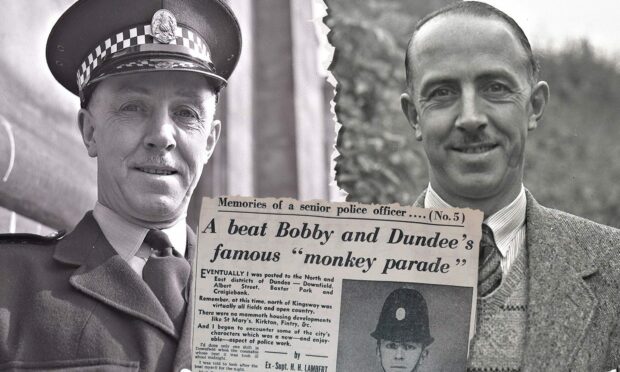

Bert Lambert wasn’t your average Dundee traffic cop.

From wartime bombing raids to gruesome murders, the man who rose to become Superintendent Lambert saw it all and more during his 34 years on the Dundee beat.

His second night on the force was the day war with Adolf Hitler’s Germany was announced on September 3 1939.

He was also the man who introduced traffic wardens to the city.

When Bert retired 50 years ago in 1973, he recalled his police days in a series of articles for the Evening Telegraph.

It was there he told of how his career had started, and how he went from completing Home Guard-type duties in the middle of a war to becoming Superintendent.

Bert Lambert

Bert was born in Ayr in 1914 and moved to Dundee in 1939.

Originally stationed in the traffic division, that all changed on Bert’s second shift.

Bert said: “I heard the announcement that the war had broken out over the radio in my digs.

“Afterwards I went for a walk to the top of the Law with one of my new colleagues, Dave Ritchie.

“We decided that the summit was the best vantage point from which to learn the layout of the city, realising that we had to become familiar with this as quickly as possible to do our job effectively.

“We gazed down on the panorama and the first thing we saw was what looked like a submarine lying just off the harbour.

“Almost simultaneously we came to the same conclusion that it was a raging German U boat.

“No doubt the prevailing atmosphere at that time coloured our judgement.

“Fortunately, we didn’t rush downtown raising the alarm, but we did linger for a few seconds just to make sure.

“Then we saw that it was really a hump of rock with a large square light on top as a warning to ships, which made it look for all the world like a submarine.

“Feeling rather sheepish, we were glad we double checked.

“The rock is still there and no doubt many other people have mistaken it for a submarine over the years.”

Memories from the War

Bert remembered when a barrage balloon came down across Arbroath Road near the Eastern Cemetery and there was a danger of it igniting as it was filled with gas.

He continued: “Then an RAF fighter nosedived into Caird Park, at Mains Loan, killing the pilot and gouging out a hole 60-70 feet deep in the soft earth.

“Later, the first bombs began to fall on the city, and I’ll never forget seeing the tenement blasted in Rosefield Street.

“There was a ragged gap in the line of buildings as if a giant tooth had been ripped out.

“High up on a wall, perched over space because floors and ceilings had vanished, a cupboard’s contents remained intact although the door had been blown off.

“This was one of the known idiosyncrasies of bomb blasts – something very close to the centre could escape the shock waves.

“So my early life as a policeman was taken up more with Home Guard type duties.

“We hardly ever looked like policemen.

“Instead, we wore steel helmets and carried gas masks.”

The departure from his normal policeman duties continued throughout the war as Bert was asked to drive the police ambulance.

His experience in the traffic department and driving the patrol cars meant he was the most experienced man for the job, although in his own words, it meant that he was “opened up to the more harrowing side of a young policeman’s life – coming face to face with sudden, violent death”.

Driving the Police Ambulance

He added: “Driving the ambulance was something I never got used to, but managed to live with because it was necessary.

“It was the only vehicle in the city for dealing with victims of accidents, fires, collapses, and drownings.

“I was frequently the first on the scene of tragedies and greeted by some gruesome sights.

“I never did manage to harden myself against road accidents involving children.”

Bert remembered a particularly difficult call out in Hilltown where he was the first responder.

He said: “I dashed in to find a woman lying dead on the floor and her son standing there with a gun in his hands.

“Before I could fully appreciate what had happened, or had a chance to feel frightened, he handed me the gun, which I very carefully placed on the piano.

“It was an odd situation.

“Everyone was very calm.

“There was no question of drink being involved – apparently it had just resulted from an argument.”

The harrowing cases and the blackouts created a challenging environment for servicemen and women during the war.

Dundee’s blackout was famed as the best in Britain: So powerful, in fact, that Bert and his colleague Dave got lost one night on their way home.

He said: “Blackout restrictions were total, and to make matters worse the high street names then were on high posts inside gardens.

“We looked at each other, well aware of our difficulty.

“There we were, two strangers to the city and dressed in police uniforms at a time when the country was rife with rumours about undercover agents being dressed as policemen.

“Dave and I trudged up and down the street for half an hour, climbing up poles to read street names – we didn’t dare show a light in case we were reported.

“We were scared to knock on a door and ask for directions.

“Eventually, we stumbled upon the correct address at Glenmarkie Terrace.

“I don’t think I’ve ever been so relieved to see a house.”

Separately to his own duties, Bert remembered the duties of other officers during the war.

He said: “Dundee established a special reserve force of policemen.

“Everyone was convinced 500 bombers would arrive at any moment to blitz the area.

“The special reserve comprised a body of sergeants and constables who reported carrying small attaché cases containing pyjamas, shaving gear, toothbrushes, etc.

“The idea was to have a mobile force of trained men able to move to any surrounding town or village in an emergency.

“They would be able to stay as long as required and maintain law and order.”

After the War

After the war, Bert visited the Police Training College in Whitburn and spent two years as an instructor.

It was during his time at Whitburn that he met Jessie, a civil servant at the college who was working as a clerk.

Shortly after, the two were married.

They had one son, Ramsey Lambert.

Bert later returned to the traffic department, and was made sergeant in 1952 before rising up the ranks in the 1960s to become inspector.

Bert eventually became Superintendent Lambert and began managing the traffic department in 1968 where his influence is still remembered to this day.

The Police Federation told The Courier in the 1980s that Bert was “largely responsible for the expansion of the police traffic department during the 1960s”.

Bert increased motor patrols in Dundee and introduced traffic wardens.

Bert retired from the force in 1973, and it was at this point that he began writing his memoirs for the Tele.

He passed away aged 67 in February 1982 at his home in Broughty Ferry.

His memoirs live on to remind us of the history of Dundee’s police force.

Conversation