Michael Alexander speaks to acclaimed author Kerry Hudson about her experiences growing up in extreme poverty.

To the outside world, Kerry Hudson is a prizewinning novelist who has travelled the world and has a secure home and a comfortable life.

But the Aberdeen-born 39-year-old, who left school at 15, knows all about growing up at the “roughest end” of poverty.

The author attended nine primary schools and five secondary schools everywhere from Coatbridge to Norfolk while living in B&Bs and council flats with her little sister and single mother.

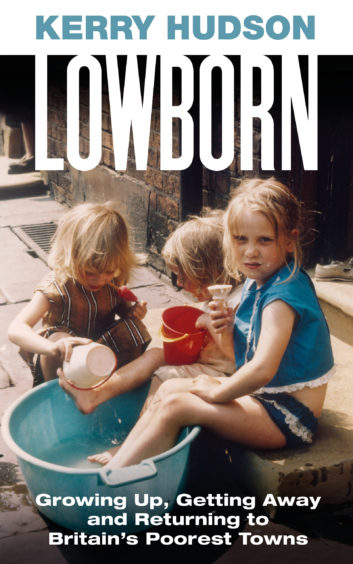

Now, as she prepares to visit Dundee University’s Festival of the Future to talk about her novel Lowborn – a book where she revisits the towns she grew up in to try to discover what being poor means in Britain today – she reveals she often finds herself looking over her shoulder as if caught between two worlds.

“The book was basically a response to Brexit happening and Trump getting in and me just seeing more and more divisive dialogue about poor people and on TV especially,” she explains.

“Jeremy Kyle gets a special mention in the book!

“I was just feeling really angry that the communities I grew up in were being so misrepresented, mainly because nobody from those communities ever got to make TV or very rarely did or very rarely got to write books.

“It felt like I was in a position to do that – and also just because I wanted to know about my past.

“I’m in a very different position now and I wanted to go back to those communities and see how they’d fared since I left and see how I felt about them.”

Kerry told The Courier how her mum, as a single parent, wasn’t able to work.

The reason they moved around so much was really that there was nothing to keep them where they were amid a belief that the “next town might be the good town”.

“You’ve got to admire the eternal optimism!” she smiles. “We were never short of that – but we were short of money!”

Looking back, Kerry says life was undoubtedly tough. But it was full of happy moments too.

“I think it’s maybe only as an adult that you look back and think actually that’s something I wouldn’t like my kid to go through,” she says.

“But at the time I wasn’t as aware of it as I might have been because I was often just around people in the same boat. It was very normalised.”

Kerry is in no doubt that poverty has always existed in our towns and cities to some degree.

But at a time when Dundee has the second highest child poverty rate in the country and the unenviable reputation as Europe’s drugs death capital, she believes, having gone back to the communities of her upbringing to write the book, that the situation is now far worse.

“One of the things that I really realised going back,” she explains, “was how even though we were so poor when I was growing up – we lived at the roughest end of poverty – we could get council houses.

“They sometimes weren’t the best council houses,” she laughs, “but we could get them. We were often in homeless B&Bs but we were always eventually rehoused.

“We did get our benefits. If something happened, we did get access to an emergency loan.

“But today – obviously Universal Credit and sanctions and selling off of social housing stock – mean that the ‘safety net’ is full of holes now.”

Another thing Kerry “really depended on” growing up were libraries. She would often hide there to read when she skived school. She is deeply saddened and angry that the country’s library system has been “completely eroded” by austerity measures.

“It was really frightening going back to communities and seeing just how much more precarious being poor in Britain is now and how much more hostile the state is to poor people,” she adds.

“But also what was really encouraging was meeting people from grassroots organisations who are working so so hard to fill those gaps. It was really heartening to see people trying to help others in their communities.”

Kerry says there’s no doubt that having experienced sharp poverty, her view of the world has been influenced. She reckons it’s made her more compassionate and empathetic than she might have been otherwise.

There are other consequences, however.

“I’m still pretty strange about money!” she laughs.

“I do my budget every day now I’m a freelancer. I want to know exactly that I’ve got enough to pay the rent, so it definitely comes with a less positive legacy.

“But I hope if nothing else it taught me that things are so much more complicated than you can ever realise. You just can’t judge a person. I think that’s a real gift to be given as an adult.”

One of the themes she explores in her book is whether people who’ve grown up in poverty can ever truly escape feeling “different” or “other” and whether they ever truly belong anywhere.

She managed to “make peace” with a lot of those questions whilst writing her book – primarily because she was able to find real pride and connection again with her roots and the communities that she came from.

She’s full of praise for some of the amazing teachers who kept her going as a youngster and “genuinely cared”.

“Teaching is such an unsung profession in terms of what they do every day for kids,” she says.

“I was really lucky that I crossed the path of some really good ones who saw that I needed some extra help and gave it to me.”

She gets angry at the politics of poverty and would challenge any assumptions about chaos and degeneracy amongst the “working class” or “poor”.

As the gulf between rich and poor widens, her advice to the “better off” in society is that they have a responsibility to contribute to their communities.

“To not judge or turn away but actually to say ‘what resources do I have – is it money, or skills or time or just understanding or empathy? And how can I contribute that?’ she says.

But she also has a message to people living in communities like where she came from.

She adds: “What I always say is ‘if I did it then you can too’. I had lots of luck but I really believe that a lot of the reasons I’ve been travelling around the country and doing free events and going to prisons is because I really want to face people and say ‘there’s really nothing very special about me but I was able to do it because I had a few little bits of luck. Maybe you’ll have a few extra bits of luck and be able to make a better life for yourself’.

“I think it’s really easy to get overwhelmed and feel hopeless – but it’s not hopeless.”

- Kerry Hudson appears at Dundee’s Festival of the Future on October 19. For more information and tickets go to www.dundee.ac.uk/futurefest