Michael Alexander examines the legacy of the critically acclaimed Black Watch play as it celebrates its 10th anniversary.

A young man wearing a brown leather jacket steps timidly onto the stage, his eyes caught like rabbits in a headlight as he peers out at the audience seated before him.

“A’right. Welcome to the story of the Black Watch,” he says, his strong Fife accent immediately recognisable.

“At first I didnae want tae dae this. I didnae want tae have tae explain myself tae folk.

“I think peoples’ minds are usually made up about you if you are in the Army.

‘What a shame. He can’t dae anything else,’ they say. ‘They get exploited by the Army’. Well I want you tae know. I wanted tae be in the Army. I could have done other stuff. I’m not a knuckle dragger!”

It was 10 years ago on August 5 2006 that the critically acclaimed ‘Black Watch’ play was first performed at the Drill Hall, Edinburgh, as part of the Edinburgh Festival.

The production, by acclaimed Dunfermline-born writer Gregory Burke, and directed by John Tiffany, took audiences on a journey from a Fife pub to an armoured wagon in Iraq and back via a potted history of the famous Black Watch regiment.

Produced at the Edinburgh Fringe in 2006 by the National Theatre of Scotland as part of the Traverse’s programme, the hard-hitting drama won 22 awards between 2006 and 2009 including two international awards, and four of the 2009 Olivier awards. It also received a motion of congratulations in the Scottish Parliament, before going on to tour the world to critical acclaim.

But more poignantly, it received the approval of real-life families, and colleagues, of real Black Watch soldiers who had died.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LVzHw979gHY

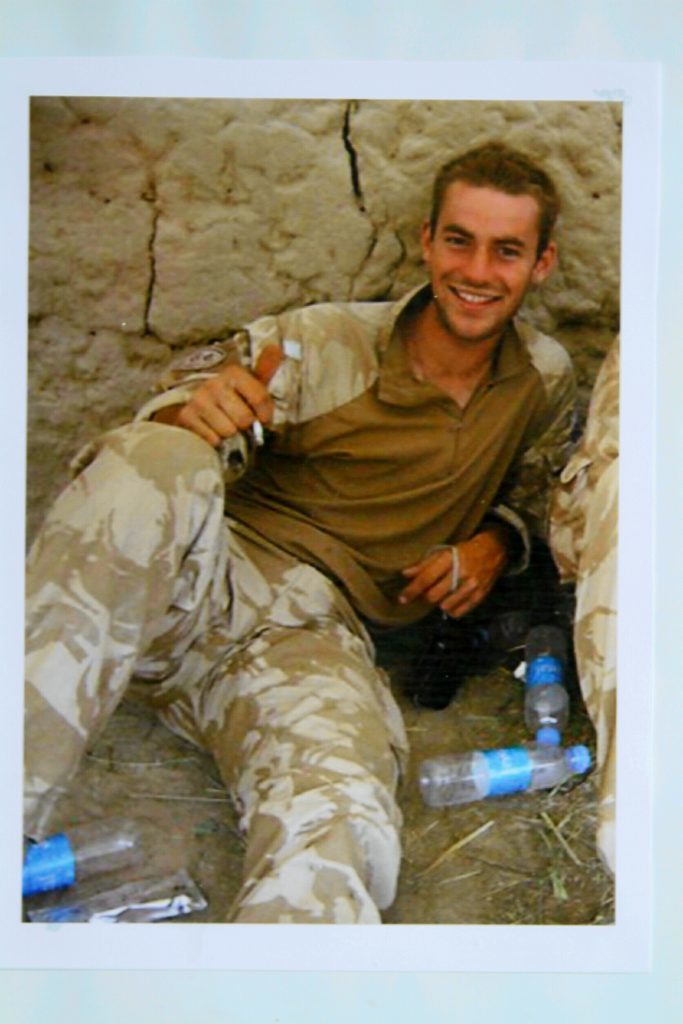

“I never had the opportunity to see it live but I have seen it since,” says former Black Watch soldier James Forrester, 28, of Methil in an interview with The Courier to mark the 10th anniversary.

“I stumbled upon it whilst looking for videos of the Black Watch in Afghanistan videos on YouTube.

“I watched it for the first time not too long after coming home from my first tour and thought it was really good. The humour and patter was exactly spot on and how it still was when I was in the army.

“From Toby tig, to discussing the first meal they were going to have when they got home were all relatable. The flashback scenes to the battalion’s history gave me a feeling of pride and gave me goose bumps and the parts where the guys were in Iraq were pretty powerful, almost too hard to watch at some points”.

James, who lost several colleagues during two tours of Afghanistan, was friends with 22-year-old Blairgowrie soldier Aaron Black who committed suicide in December 2011 just seven months after being discharged from the army. James says he was the first to admit he got “pretty emotional” at some of the scenes.

But it was this realism that made it work, he says, adding: “Overall, I thought it was an excellent show that hit the nail on the head with giving the public a snapshot of a modern warzone, the emotions, frustrations, humour all felt very real.”

The realism of the play came from the fact it was based on interviews with veterans from writer Gregory Burke’s own Fife – at the heart of the Black Watch’s traditional recruiting ground. This gave it a powerful, violent, funny and often poetic look at Scots at war, containing strong language, loud explosions and strobe lighting.

The opening scenes see a writer interview a group of young servicemen as they drink and play pool.

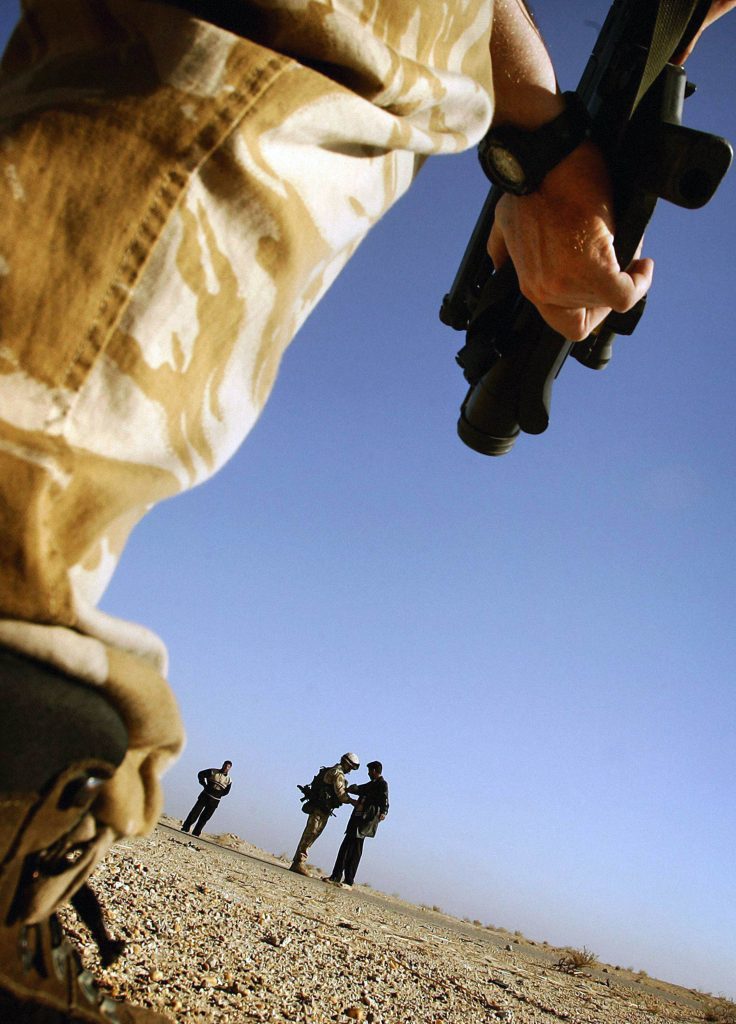

The audience sees them again in the desert at Camp Dogwood, set in 2004.

At a time when the real-life Black Watch was regularly in the news – all too often as a result of taking casualties in Iraq and Afghanistan – the play revealed what it meant to be part of the legendary Scottish regiment, what it meant to be part of the so-called ‘war on terror’ and what it meant to make the journey home again.

The production made powerful and inventive use of movement, music and song.

It received global acclaim and had celebrity fans such as Sean Connery, Hugh Jackman and the Coen Brothers.

The National Theatre of Scotland’s director of external affairs, Roberta Doyle, tells The Courier that the authenticity of the play was its use of powerful language and vernacular.

“One of the commanders in the real Black Watch who helped us make the production and was interviewed by the BBC was asked whether the swearing was authentic. He said ‘no, they swear a lot more than that in real life!’”

But Roberta said audiences never complained about the strong language – even on the tour of America where eyebrows were initially raised about the use of the ‘C’ word.

She adds: “I think the legacy globally is extremely sad. That we are still conducting wars around the world where these countries are still topical.

“Another particular theme of topicality was the issues around friendship and masculinity. A lot of men in the audiences responded in a way they weren’t expecting. There’s that scene when the soldier says he ‘fought for his mates’ and that struck home – the grand universal themes of love and death.”

Roberta said thousands of real military had watched the play around the world and the most moving feedback had been the revelation from real soldiers that the play “gave them a voice that they had never had before.”

“It spoke of Scotland, “she says. “It spoke of being in the Black Watch and being from Black Watch territory, of being in places like the Perth Road. It spoke of their unique experiences and of that Golden Thread through army families dating back centuries in the Fife and Tayside areas.”

Ten years may have passed, but the Black Watch play remains as powerful, and as relevant, as ever.

malexander@thecourier.co.uk