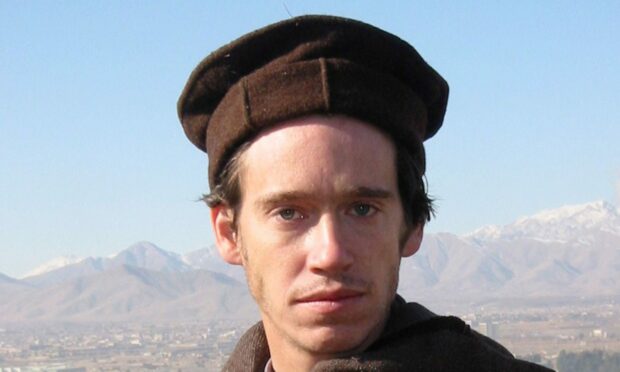

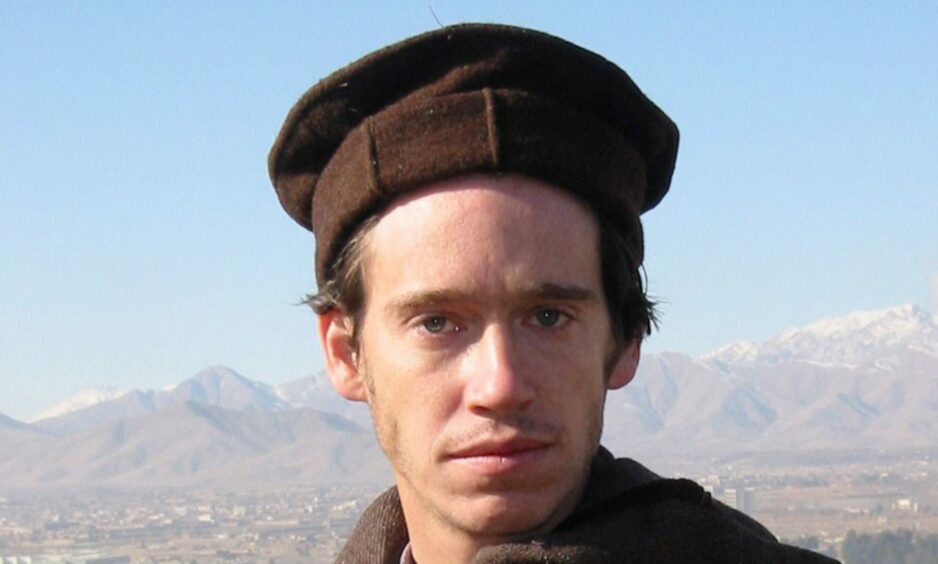

Rory Stewart has had an incredibly wide ranging career as a politician, academic, writer, adventurer and as a co-host of leading political podcast The Rest is Politics with Alastair Campbell.

More than 20 years ago, after a brief time in the army and the diplomatic service, the now former politician with links to Perthshire and Angus, walked 6000 miles over 21 months on a trek across Asia.

He became the acting governor of the province of Iraq, established an NGO in Afghanistan and of course entered the House of Commons as an MP.

What else has Rory Stewart done?

He served as a Conservative minister before his recent unsuccessful bid to be Prime Minister.

The former UK Secretary of State for International Development is now president of the not for profit organisation GiveDirectly.

His life story, including a brief stint with the Black Watch, was colourful enough to attract Brad Pitt’s interest for a potential movie, with Hollywood superstar Orlando Bloom even touted to play Mr Stewart at one point.

When the now 50-year-old walked into the hall at the North Inch Community Campus in Perth, however, it was simply to share stories about his walk across Afghanistan, which he undertook shortly after the US invasion of the country in 2001, and which he described so beautifully in his award-winning best-selling book The Places In Between.

Recalling adventures in Afghanistan

Dressed in a tweed jacket and kilt that honoured his roots near Crieff, Rory was a “wee bit jet lagged” having not long flown in to Scotland from Jordan.

However, the often humorous account of his adventures in Afghanistan was undimmed as he spoke to a sell-out crowd at the event hosted by the Perth-based Royal Scottish Geographical Society, which awarded him the prestigious Livingstone Medal in 2009.

“This was a walk that I did in the winter of 2001/2002 – so just after 9/11,” he explained.

“I had been walking by that stage across Iran, tried to walk across Afghanistan but the Taliban wouldn’t let me in.

“So I continued across Pakistan, India and Nepal and I got to just approaching the edge of Bangladesh when the Taliban fell and I had the opportunity to fill in the bit in-between by walking from Herat to Kabul.”

‘Brutal series of political changes’

Rory described it as a “very interesting time in Afghan history”.

The Taliban government had fallen.

But the new government had not really taken over.

President Karzai was in charge of an interim administration in Kabul.

But in the mountains and the villages there was essentially a vacuum which, to some extent, he said, had been there since the mid-1970s.

“Afghanistan had been through this brutal series of political changes – an invasion by the Soviet Union, a big resistance movement, the Taliban takeover after a period of civil war,” he said.

“And so many of these communities hadn’t seen very much of the outside world in 25 years or they’d only seen the outside world through very particular things – through the purchase of a Kalashnikov, or the acquisition of a big bundle of wheat from the World Food Programme.

“Connections to the world were through the United Nations agencies, connections to the world through the CIA supplying them with Stinger missiles.

“But otherwise not a great deal of connection to the outside world.”

What was Afghanistan like in 2001/2002?

Normally Rory would walk alone. But near the start of his walk, the local governor had insisted that three of his gunmen walk with him.

Rory was “very very uncomfortable” about this.

Much of the first 10 days was spent trying to persuade them to leave him alone, as he felt he was in much more danger with these people than if by himself.

Describing Afghanistan as the ‘roundabout of the ancient world’ – and laughing it was a “bit like Broxden roundabout” at Perth – he explained that people would traditionally go north around the central mountains, as Alexander the Great did, or south as “most of the people did on the hippy trail”.

By contrast, he walked directly through the central mountains from west to east.

The only other person recorded in history to have done this was Babur, the founder of the Mughai Empire in the Indian subcontinent who was a descendent of Genghis Khan, and who made the journey in 1492.

“Surprisingly there was an enormous amount that was extremely recognisable in terms of geography, landscape and villages,” he said.

“But even earlier still, there is an Arab geographer from the 10th century who says that as you walk from Herat east, the land is flat for the first seven days before you reach the hill country.

“This was my introduction to one of the first and most useful lessons I learned on the walk which was the importance of looking for sheep poo!

“Sheep poo is your great indicator that there is unlikely to be a minefield!”

Beautiful Afghan people and landscape

Rory detailed a beautiful landscape of desert, mountain and ancient forts – littered in places with rusting Russian armoured personnel carriers and other abandoned munitions.

He talked of generous, hospitable and courageous people who’d experienced great hardship.

When the snows began to fall in January 2002, he gained his first insight into the “great competitive advantage” of the Afghanistan economy – opium poppies!

“It was the only country that was able to produce 92% of Europe’s heroin while still receiving $4 billion per year in international development!” he said.

Rory talked in detail of his encounters with people, places and culture as well as his acquisition of a dog which became his close companion.

Why did Rory move to Afghanistan?

A few years after his walk, he moved to Afghanistan and set up a charity called Turquoise Mountain.

It essentially began restoring the old city of Kabul.

He also set up a calligraphy school, took out 25,000 truck loads of garbage from the old city, laid paving and improved the water supply.

He revealed he had been back to visit many of the places he walked through since setting up the project.

His wife was in Afghanistan just a few weeks ago.

What’s the impact been of US/UK mlitary withdrawal?

“Surprisingly”, he said, following the controversial withdrawal of US, UK and other western troops from Afghanistan in August 2021, meetings with the Taliban government had been possible as they try to keep the project going.

At a local level the Taliban have been “much more flexible than you’d think”, he said, and seemed happy having women doing vocational training.

His wife had also found improvements in security since 2021.

However, he added: “We shouldn’t give the Taliban too much credit for that – the reason we haven’t been able to do much for 15 years is because the Taliban have been trying to kill us!”

Was western vision a ‘fantasy’?

Rory recalls how at the end of the 1990s, western governments thought Afghanistan would become a modern democracy.

In 2002, its own acting leader was committed to a “gender sensitive multi-ethnic centralised state based on democracy human rights and the rule of law”.

Looking back, however, Rory describes it as like a “bland western fantasy”.

Rory also questioned western attempts to change the behaviour of the Taliban by sanctioning them.

“They are not people who want to go shopping in Harrods,” he said.

“They are people who’ve spent 20 years living in caves.

“They’ve just defeated the greatest military in the world – the US was spending $150 billion per year on Afghanistan.

“The Americans had the latest cyber technology. The latest AI. The latest drones. The latest missile systems.

“The Taliban essentially defeated them on ponies with Kalashnikovs which is a piece of 1947 Russian technology.

“The consequence of our refusing to engage with them is that the Taliban are not suffering. But the Afghan people are suffering terribly.

“I think that we have to acknowledge that we spent more than 20 years trying to dislodge the Taliban and we gave up.

“I often think that our refusal to engage or provide development assistance is sour grapes.

“We are just angry that we were defeated and have been humiliated and we don’t want to have anything to do with them.”

What’s the impact of climate change?

Rory also warned that climate change is impacting “very very starkly and very terribly” on Afghanistan.

A terrible drought two years ago left nearly 150,000 people on the edge of starvation.

People were selling their own organs to keep their children alive.

It’s even more stark in Iraq and Iran, he said, while Jordan is much less green than it was 10 years ago.

The situation in Somalia is also “terrifying”.

“One thing we need to talk about when we talk about climate change is the impact on the extreme poor,” he said.

“Climate change will of course affect us.

“But if you are living on less than two dollars a day, if you are eating once every two days, if you have literally no savings and that drought is what kills your only cow or your only sheep, you have nothing left.

“In Europe and the United States, yes it’s terrible, but most of us have governments who can provide a bit of assistance.

“People can ultimately move house. Move inland.

“They can restart their lives.

“That’s not true if you are living in central Afghanistan or Somalia.”

What’s the impact of budget cuts overseas?

He added: “One of the sad things is that the focus on climate change means that a lot of money that used to go into international development assistance is now being diverted to Indonesia, to China, to middle-income countries to try and wean them off coal.

“When I ran the Department for International Development, we had a budget of about £20 billion dollars a year.

“My bilateral budget in Africa was $4.5 billion, the multi-lateral budget another $3 billion on top of that.

Last year the British government had cut its development assistance to Africa to approximately one tenth of what it was in 2016.

“It’s not just the British. The Swedes, the Norwegians, they are all cutting.

“The Americans are now covering 90% of all the funding for drought relief in places like Somalia.

“Without America there could basically be no emergency food assistance going to those communities. And we don’t talk about that enough.”

Conversation