Michael Alexander finds out about the chequered history -and fragility – of the Declaration of Arbroath as its 700th anniversary is marked on April 6.

It is one of Scotland’s most important historical documents, capturing a powerful call for the recognition of the Kingdom of Scotland’s sovereign independence.

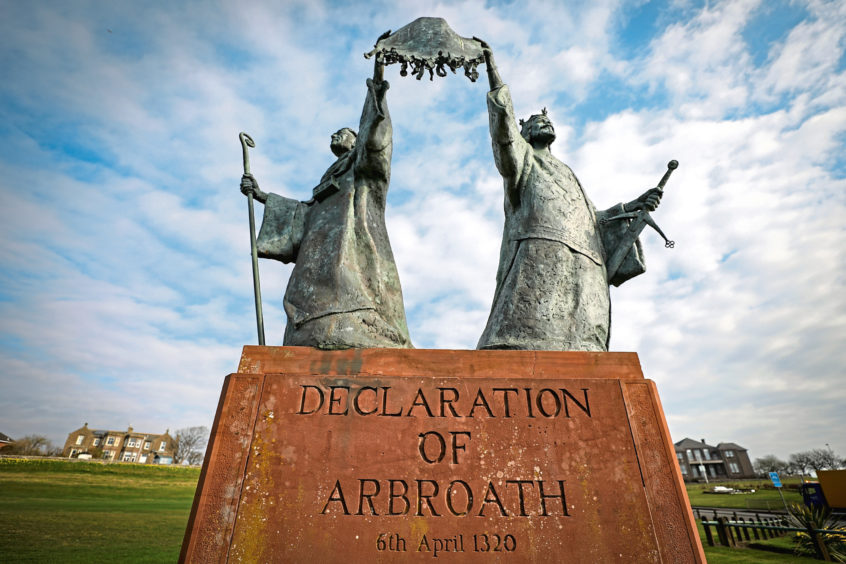

The Declaration of Arbroath, which would have gone on display at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh on Friday March 27 if the museum hadn’t been shut as a precaution against the coronavirus is a 700-year-old letter dated April 6 1320, written by the barons and freeholders of Scotland, on behalf of the Kingdom of Scotland.

The letter to Pope John XXII, written following victory over the English at Bannockburn in 1314, asks him to dispassionately recognise Scotland’s independence and acknowledge Robert the Bruce as the country’s lawful king.

The letter also asks the Pontiff to persuade King Edward II of England to end hostilities against the Scots, so that their energy may be better used to secure the frontiers of Christendom.

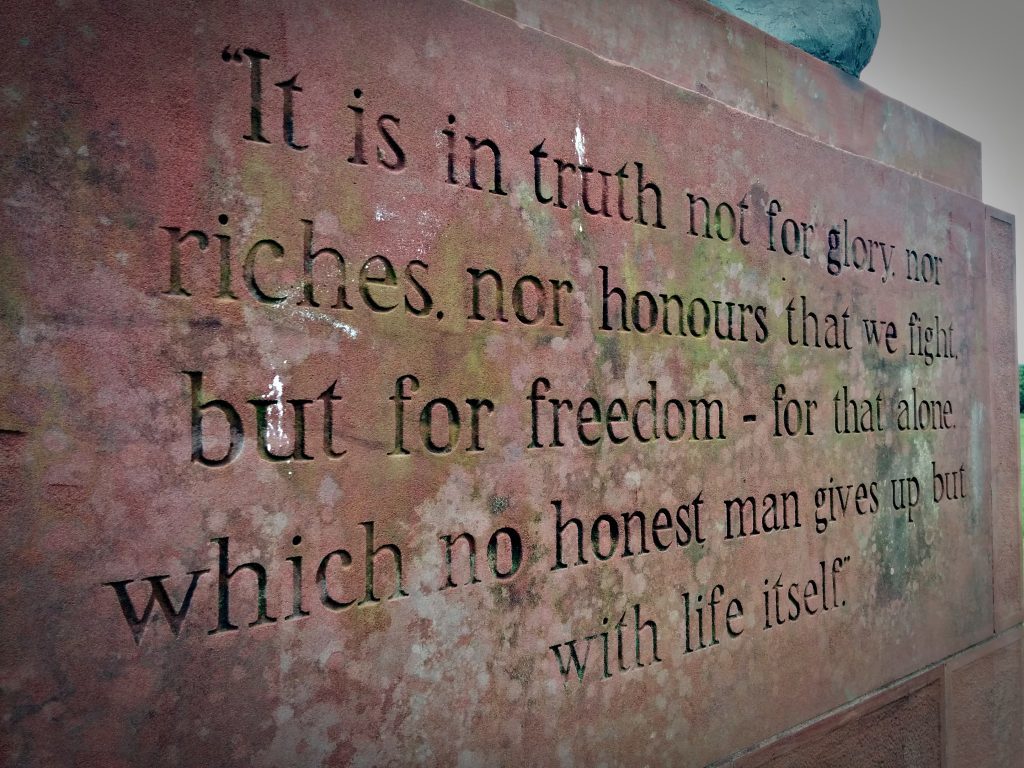

It famously said: “For as long as 100 of us shall remain alive, we shall never in any wise consent submit to the rule of the English, for it is not for glory we fight, nor riches, or for honour, but for freedom alone, which no good man loses but with his life.”

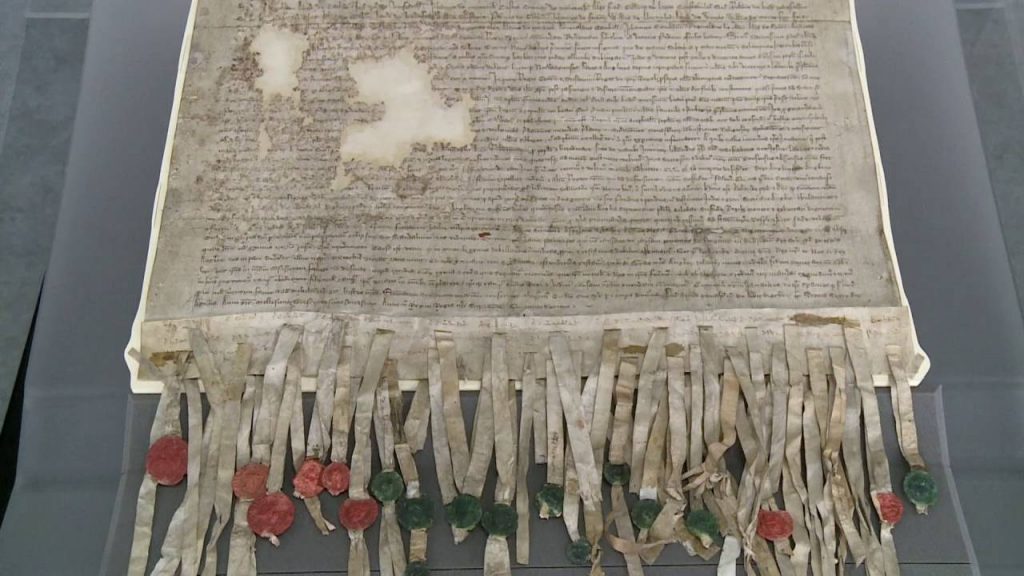

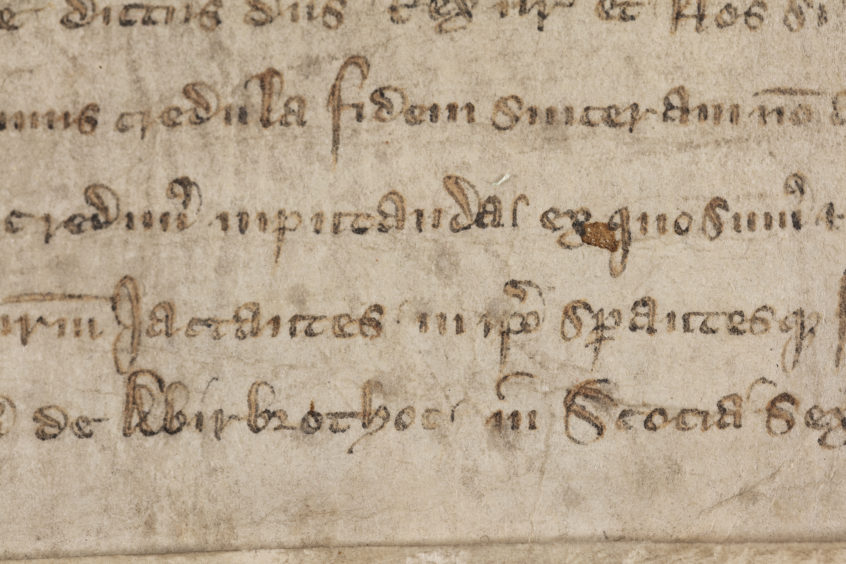

Written in Latin, the Declaration was written up in the scriptorium of Arbroath Abbey – probably by Bernard de Linton, Abbot of Arbroath and Chancellor of Scotland – and was sealed by eight earls and about 40 barons.

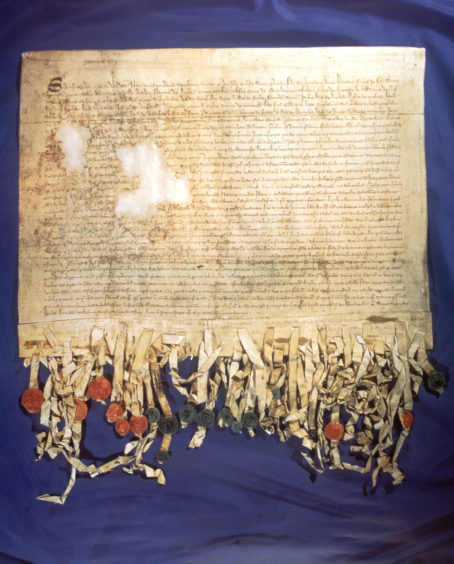

It was authenticated by seals, as documents at that time were not signed.

Today, only 19 seals remain, and the iconic and fragile document, which is cared for and preserved for future generations by the National Records of Scotland, can only be occasionally displayed in order to ensure its long-term preservation.

But according to Dr Alice Blackwell, Curator of Medieval Archaeology and History at National Museums Scotland, there are many “misconceptions” about the Declaration that persist.

She hopes that when the chance does arise at some point in the future to put it on display in Edinburgh – integrated into the museum’s regular medieval display to reflect its position in the story of Scotland – it will help people understand “what it isn’t as well as what it is”.

“The first thing that’s really quite interesting about it is that the name the Declaration of Arbroath is only about 100 years old,” said Dr Blackwell.

“That’s interesting because it’s kind of misleading. A Declaration makes it sound like almost a legal document.

“But the reasons why it was sent – the context around it – is really interesting.

“It was sent from the barons and earls of Scotland to the Pope.

“On the face of it, it looks like a letter written from the communities of Scotland.

“But it was very much a government initiative. It was the brainchild of King Robert I, Robert Bruce.”

Dr Blackwell said Robert Bruce had to write to the Pope for two sets of reasons.

The first was the context of medieval international politics.

It was written during the Wars of Independence with England and Robert Bruce had been ex-communicated by the Pope. He was suffering “pretty staunch” international sanctions at this point for having broken a truce that the Pope wanted when he retook the former Scottish town of Berwick from the English in 1318.

“The worry was that the Pope would side with England and not recognise Scottish sovereignty and not recognise Robert’s legitimacy as king,” said Dr Blackwell.

“Robert Bruce being ex-communicated put him at a disadvantage. But it was more than that.

“The Pope demanded that Robert Bruce come to Avignon to explain himself.

“Robert wasn’t about to do that so he wrote instead and this was the letter he sent instead.

“At this time the Pope is not just head of Christendom but he’s kind of acting like an international arbitrator – something akin to the UN.”

Dr Blackwell said the second set of reasons why Robert Bruce had to send the letter was that he was a “little bit vulnerable at home”.

“Robert Bruce’ heir, his grandson (Robert II), was only four years old at this time,” she said: “so his dynasty if you like – his future – was kind of vulnerable.

“It meant that if somebody could take Robert Bruce’s place, there wasn’t a natural grown up mature heir to resist that.

“We know that later in the summer of 1320 there was a conspiracy against Robert Bruce. Some of the barons that signed this letter were later shown to have been part of this conspiracy against Robert Bruce.

“The background to Robert Bruce taking the throne in Scotland in 1306 was because the legitimate king of Scotland John Balliol was absent.

“Balliol had in effect ceased to function as king. He was the official crowned legitimate king of Scotland. So there was a slight air of illegitimacy at the start of Robert Bruce’s reign.

“The son of John Balliol – very close to King Edward I of England – is not far away. So there’s a contender to the throne on the scene.”

Before becoming known as the Declaration of Arbroath a century ago, Dr Blackwell said the 700-year-old document carried a very long and literal description along the lines of ‘A letter to the Pope by the barons and freeholders of Scotland’.

She said the reason why it’s well known abroad – particularly in North America – is the perception that this document inspired the naming of the 1776 US Declaration of Independence.

But while Dr Blackwell said it was a “really nice idea”, she added: “Historians haven’t actually found any evidence to support that.

“What we do have is the suggestion that it’s the other way around – that the name the Declaration of Arbroath is later influenced by the name of the US Declaration of Independence.”

Dr Blackwell said the idea behind the Declaration of Arbroath was drafted at a full king’s council at Newbattle Abbey near Edinburgh in March 1320.

The fair copy – of which the document now on display is the only survivor – was written up at Arbroath Abbey because that’s where Robert I’s writing office – the chancellory of government – was located at the time.

It’s message ultimately succeeded, at least for a while, because in 1324, the Pope recognised Robert I as king of an independent Scotland, and in 1326, the Franco-Scottish alliance was renewed in the Treaty of Corbeil.

But while “immensely excited” that the document still create a buzz, Dr Blackwell said the final misconception is the document itself was “very special” at a time when such parchments were relatively run of the mill.

“It’s very special that it survived,” she said.

“But the letter that was sent to Avignon – the copy that actually went to the Pope – is lost. What Scotland did was keep a ‘file copy’ that was written at the same time. It’s still 700 years old and that’s the document that survives today that we call the Declaration of Arbroath.

“To say that having this on display is quite a big deal is an understatement. It’s immensely exciting!

“To put this into perspective, it’s so fragile that I’d never previously seen it in the flesh.”

The fragility of the document means that extreme care has to be taken about light levels and the number of hours it can be exposed.

Susan Corrigall, Head of Preservation at National Records of Scotland (NRS) explained that the document is ordinarily housed in one of NRS’ archival store rooms which contain 80 km of archival shelving comprising Scottish records dating back to the 12th century.

The Declaration lives in an environmentally controlled cabinet in an extra secure room.

While its relatively short journey across Edinburgh to the museum didn’t happen in the end after being stalled by coronavirus, however, the plan was for document to be transferred in a special air conditioned, rear suspension truck on a route planned in advance.

The document itself would have been moved in a case within a case designed so that it wouldn’t get knocked. A walk through had even taken place well in advance to its exhibition place within the museum.

“The document itself is really fragile,” said Susan. “It’s about A3 size roughly.

“Now there are 19 seals remaining, so it’s wobbly. It’s bottom-heavy with the seals on the bottom. It has to be supported throughout the structure. That makes it challenging.

“But what documents like the Declaration of Arbroath really don’t like is light.

“The Declaration of Arbroath would be most happy living in a darkened room – never coming out for public display – because light damage is cumulative and irreversible towards such objects.

“In relation to the display at the museum, my head of conservation at NRS worked out a light budget. That is the intensity and duration of light which we feel the Declaration of Arbroath can be safely exposed to for the period of the exhibition without causing undue additional damage.

“Because of its physical fragility, we take it out of the store room as little as possible. In the more than 20 years I’ve worked here, I saw it for the first time last summer!”

Susan said that over 700 years the surviving document has had “quite a chequered history”.

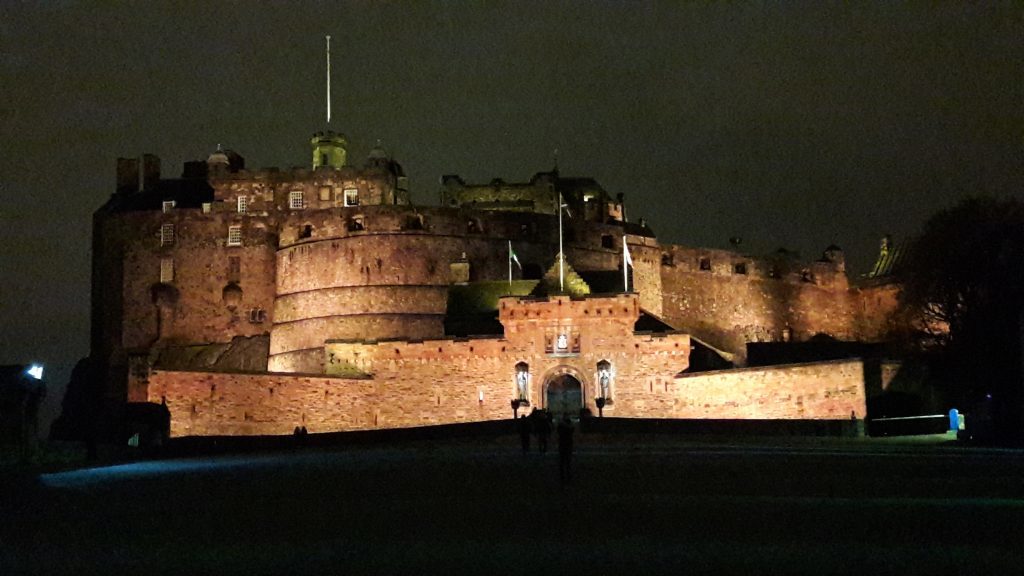

It was kept with the rest of the national records in Edinburgh Castle until the 17th century. When work was being done on the castle, the Declaration was taken for safekeeping to Tyninghame in East Lothian.

While there it suffered damage through damp and it returned to the custody of the Deputy Clerk Register (the predecessor of the Keeper of the Records of Scotland) in 1829.

“There was a tale – a rather good tale – that it was used as a fire screen during it’s time at Tyninghame House,” said Susan.

“My team think that’s probably apocryphal. But it’s a good story!”

As our understanding of how to control, manage and look after fragile documents has improved, the NRS is now “hyper-conscious” about preventing future damage while accepting that nothing can be done about damage caused in the past.

But the NRS also accepts that the document’s scars are part of its story.

“One of the really quite wonderful things about an iconic document is that it starts to take on a life of its own,” she said.

“It means so many different things to different audiences.

“To my conservation colleagues it’s a parchment document with pendant seals.

“To a medievalist it’s an important part of the medieval story of Scotland.

“To a political audience there are quite different resonances.

“That’s incredibly powerful. As someone tasked with looking after and preserving the document, one is neutral to those different stories and those different reactions and responses.

“But I must admit the first time I saw the document I got quite a thrill.

“I just got a buzz through my whole body.

“It’s living in a physical sense as well because it’s made of parchment which is animal. “Originally it was thought it was made of calf skin but now we think it might be sheepskin. It’s very difficult to tell either way which it is conclusively.

“Something else I find really exciting and engaging about it is the document is made of recognisable things.

“Parchment, the seals – they are beeswax seals. The green seals are made of verdigris – a copper oxide and the red seals are made of a powdered mineral called cinnabar.

“It’s recognisable and the ink is iron gall which was common across Europe until the 19th century.”

*The National Museum of Scotland has postponed all scheduled exhibitions and events until further notice due to the coronavirus, including the display of the Declaration of Arbroath. The plan is to reschedule an exhibition at a future date.