When retired social development specialist Kate Phillips set out to write a book that explored Scotland’s role in Jamaican slavery and the roots of modern racism, she started off with some simple questions:

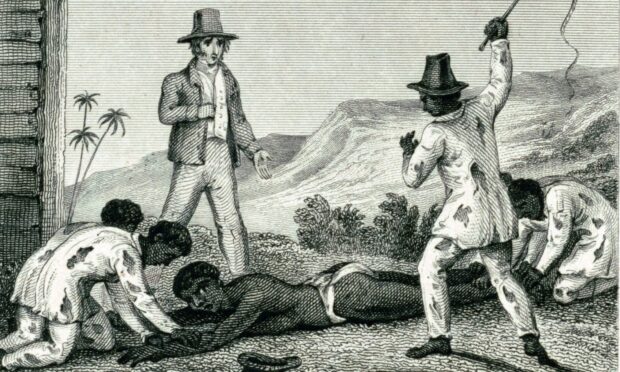

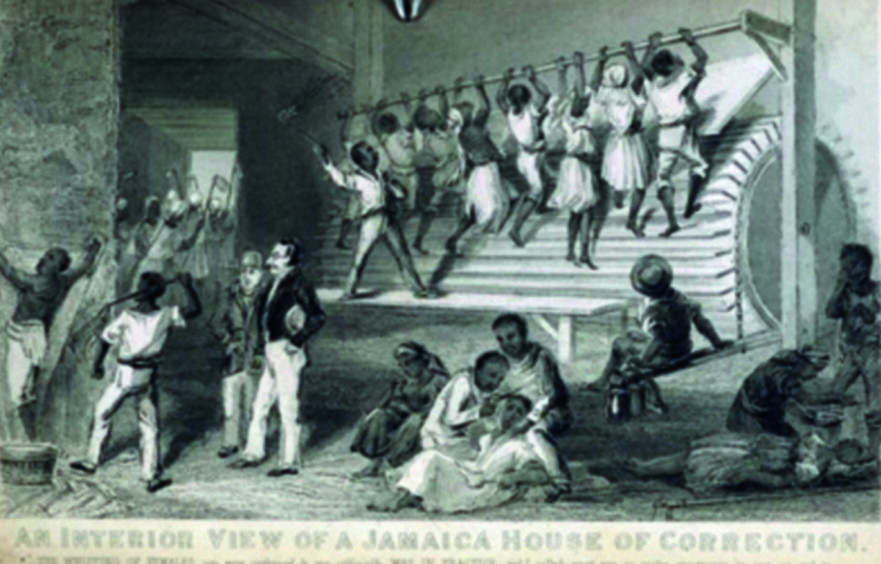

How did so many thousands of educated Scottish Christians become involved in slavery in Jamaica, and how did they justify their lifestyle to themselves and to others?

What did Scottish newspapers, popular historians, philosophers and the public think at the time?

Did they tell themselves that black lives didn’t matter because white people were regarded as superior to anyone with a darker skin?

First-hand accounts

To find out more, she needed first-hand accounts from the 1700s when Scots first crossed the Atlantic and encountered Africans.

She traced the letters, parliamentary debates and newspaper reports of the time which recorded the many reasons why people from Scotland crossed the Atlantic, the ambitions they had and where those ambitions took them.

Accounts of Scotland’s connection with slavery often dwell upon Scots’ advocacy for abolition.

Yet Bought & Sold: Scotland, Jamaica and Slavery shifts the focus.

After discovering “more harrowing and complicated” findings than she could ever have anticipated, the book recognises that many Scots were enthusiastic participants in slavery.

However, it also promotes awareness that the abolition of slavery was not an end: it was only a beginning.

She also concludes that the legacy of “ugly, racist views designed to hold down slaves” persists to this day.

Scotland’s role in the slave trade?

“Scotland was one of the major centres of the slave trade,” says Kate.

“If we think of Scotland as being around a tenth of the British population in the 1700s/1800s, we were about a third of those involved in all aspects of the slave trade in Jamaica.

“We bought and sold slaves, we made lots of money through slave ships.

“We were dealers in slavery but we were also plantation owners and owners of slaves. Our bankers and insurance companies were at the heart of the business end.

“About a third of the money made in Jamaica was by Scots, so comparatively it was more important to our economy than it was to England, which is why the Scots fought so hard to hold on to slavery.

“We were involved in the abolitionist movement as well. But we were a divided country.

“It’s only more recently that somehow we’ve become ignorant to the big battles for and against slavery that went on, with Scotland at the centre of it.”

How did Kate get interested?

For over 40 years, Kate researched, taught and prepared educational material for rights activists, trade unionists, members of parliaments and would-be politicians in the Caribbean, Africa, Asia, the Middle East and Pacific Islands, where she travelled widely.

Through her work at Glasgow University, she used to bring over groups of mature students from the Middle East and Africa.

While the groups were always happy to be in Glasgow, she noted they were always a “little bit fearful about racism”.

It was through these experiences that she got thinking about Scotland’s role in the slave trade and why, almost 200 years after slavery’s abolition in Britain, racist perceptions or fear of racism continue – particularly amongst older generations like her own.

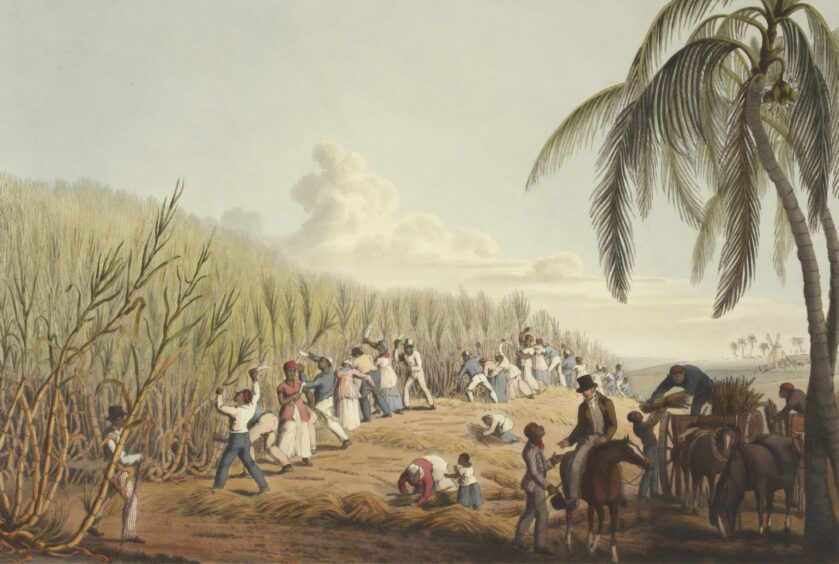

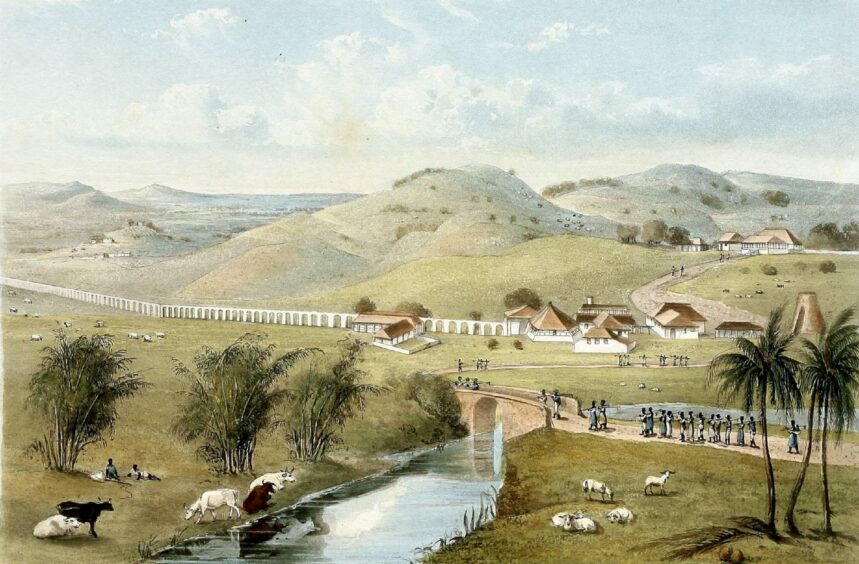

The book traces the story of how and why thousands of Scots made money from buying and selling humans.

But Kate feels it’s a story the country still needs to “own” and admit to.

Many Scots were at the heart of the slave industry.

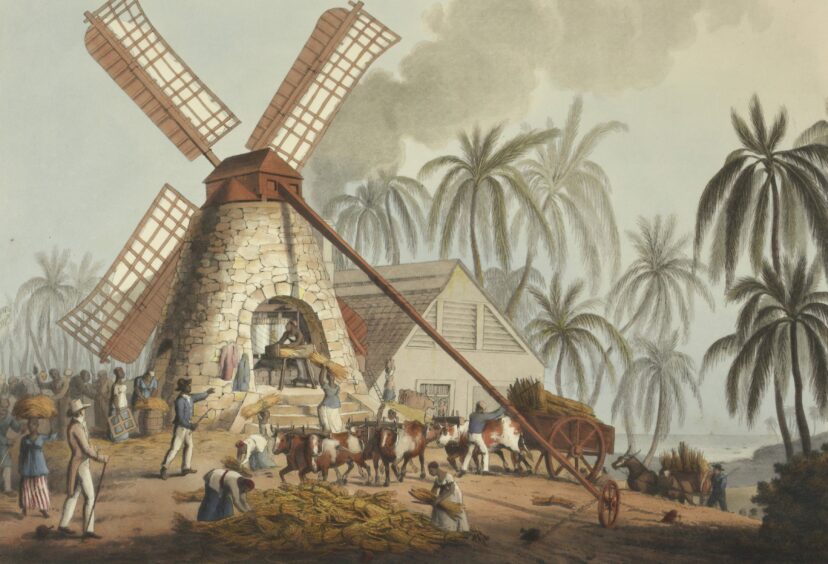

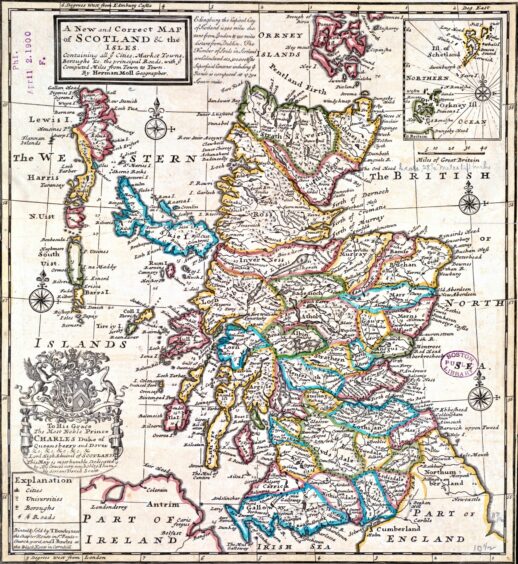

The union with England in 1707 gave Scotland access to both trade and settlement in Jamaica, Britain’s richest colony and its major slave trading hub.

Tens of thousands from Scotland lived and worked there. Others campaigned against it.

Yet the fortunes of Scottish plantation owners, merchants, traders, bankers and insurance brokers were threatened by the abolition campaign and slave revolts.

“In the 1700s and 1800s Scotland was very religious and well-educated,” she says.

“So how did we justify slavery? How did we square that up with our religious beliefs?

“That was something I wanted to understand.

“Even the Church of Scotland hierarchy were ambivalent about slavery – they didn’t condemn it.

“But the ordinary people felt differently. They read their Bibles and they understood ‘a man’s a man for a’ that’, and they didn’t believe that God created different sorts of men – only one type of men and women and they were God’s children and were valued the same.”

Scotland’s role in birth of racism

Kate says that before the 1700s, there was no evidence of racism as a concept. There was rich and poor, irrespective of skin colour.

In Scotland, before the Act of Union, there had been sugar refining on the Clyde from the 1650s/60s.

The “push” factor came, however, when traders from the west began to realise there was a lot of money to be made in the Caribbean sugar industry.

In contrast to Scotland where much of the land was coarse and difficult to make money from, they became increasingly aware of good quality land overseas which was easy to farm and turn into profit.

Other factors were the dismantling of Scotland’s run-rig system, which helped push people off the land, opening of new markets after 1707 and the fleeing of landowning sons to Jamaica after the Jacobite risings of 1715 and 1745.

Kate says once families had a piece of land in Jamaica, they often became multi-generational trans-Atlantic operations.

Plantation owners might return home and send their sons or nephews out to manage the slave business.

What’s interesting, however, is that while slave plantations grew in the Caribbean, it was back home in Scotland that the money was banked, insured and ultimately spent.

Which Scottish families were involved?

“If we look at the Shand family in Kincardineshire,” says Kate, “they transferred more than £127,000 in those days back to Scotland from Jamaica.

“That’s not just a fortune – it’s an unknown amount of money in those days!

“Look at the Grant family. The original Grants were doctors, but they got into buying and selling slaves and were partners in Bunce Island which is the island in modern day Sierra Leone where thousands of slaves were sold.

“These days, if we trace down through the years, decendants have still got business interests in Scotland and there’s still money and land linked to that time.

“Another was the Taylor family originally from Montrose. They were compensated for 2000 slaves at the end of slavery.

“If you drive around Scotland and look at estates – especially those with beautiful houses and nice wooded parks around them – then you usually find they originally came from slavery.

“The money either came from Virginia or the Caribbean.

“We didn’t make that kind of money in Scotland out of Scottish land!

“But often the money never left Scotland to begin with because our banking and insurance business was here.

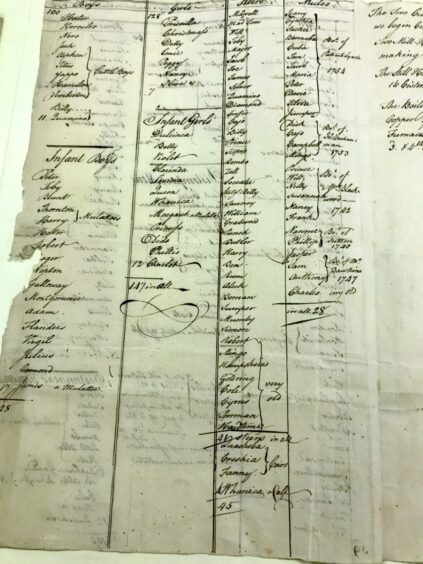

“If someone in Jamaica needed to buy slaves, then they’d get a line of credit from a merchant bank in Scotland – Edinburgh or Glasgow. They could then bid in the slave market in Kingston for the slaves that they need.

“When the merchants in Glasgow have cleared enough lines of credit, then they would fund a ship go down to Africa to collect the slaves that were needed and take them to Kingston.

“All the transactions went on in Scotland, and that’s what the law allowed.

“Although you couldn’t live as a slave in Scotland after the late 1700s, until 1834 you could still buy and sell slaves in Scotland on the Scottish banking ledgers.

“The merchants who lent the money were also the merchants that received the goods – the cotton and the sugar back again into Scotland. They processed it and sold it and the money made from those sales paid off the loans people had taken.

“We might look at people who own slaves, people who worked the land in Jamaica.

“But the people who really made the money were the merchants who leant the money and controlled the slave buying and selling business.”

Why should the past be understood?

Kate feels it’s important for Scotland to know and understand it’s past now because it’s only through this that Scotland can understand how it helped “invent” racism.

“Before slavery people were people and there were wealthy people and poor people,” she says.

“The colour of their skin didn’t really matter.

“Until we actually free our consciences of all of that stuff and understand how we constructed a kind of apartheid system in laws and the way we thought about things, that’s the only way we are going to bring about change.

“I don’t think we’re there yet but I do think things are changing and changing quite rapidly.

“I’m very hopeful that the younger generation won’t care about race as a concept. People will be seen as just people.”

Bought & Sold: Scotland, Jamaica and Slavery by Kate Phillips 978-1-910022-55-9 paperback £11.99.

Conversation