I have been looking at the figures for Covid-19 in Scotland and England, and the differences are striking.

In the week to last Thursday, there were over 80 daily deaths on average in England. In Scotland the average was less than one death every two days.

As for infections, there were just under 10 new daily cases per million people in England. In Scotland, there was just over one.

In England, some two planeloads of people are dying weekly. In Scotland, we are approaching elimination of the disease (though we mustn’t be complacent – we aren’t there yet and if we don’t stick at it, infections could quickly spike again).

So why the difference? What has Scotland got right that England has got wrong?

The first thing to recognise is that, when it comes to something as complex as cross-national comparisons, there is no simple answer.

In terms of geography and population, Scotland and England are different countries.

Factors like population density and levels of international travel (which first introduced the disease) probably played a part, but not enough to explain the whole difference.

For that, we need to turn to the different pandemic policies of the Westminster and Holyrood parliaments. The second thing to recognise is that Holyrood didn’t get everything right. Far from it.

Like Westminster, Scotland was slow to recognise the scale of the threat, slow to develop adequate testing facilities and too slow to lockdown.

That cost many lives, as did the disastrous decision to move elderly people from hospitals into care homes.

But – and here the differences begin – the Scottish Government has acknowledged its errors and responded nimbly to the developing understanding of the disease.

As a consequence, its policies have diverged from Westminster in four key regards.

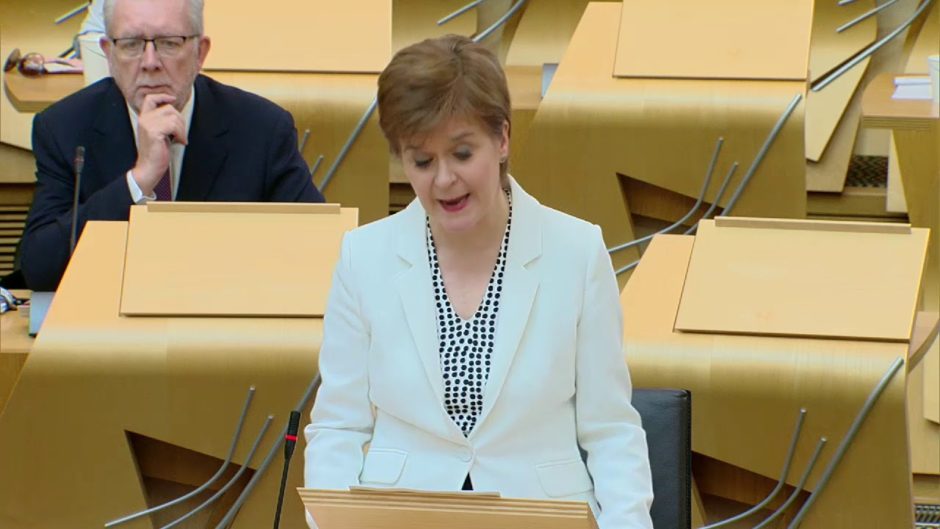

First and foremost, Nicola Sturgeon has articulated a clear overall strategy based on elimination of Covid-19. This doesn’t mean that we will get to zero and stay there.

But it means a constant drive to lower the infections and deaths and a refusal to be satisfied as long as people are still dying.

That stands in stark contrast to the lack of any clear strategy from Boris Johnson’s government.

Second, Holyrood has developed a clear, co-ordinated set of policies to realise its strategy: Caution in reopening before infections are driven down to a level where we can do so with confidence, a local-led testing system, maintaining social distancing and a clear policy on wearing masks.

Again this contrasts to the combination of hasty and ad hoc measures in England which has no clear logic beyond, perhaps, stimulating headlines about “Super Saturday” and “Independence Day”.

Third, the communication in Scotland has been clear and consistent, both in terms of the overall understanding of the pandemic and the specific measures to combat it, in terms of words and actions.

In Scotland (unlike England) politicians and officials have done as they tell us to do – or, if they haven’t, they have paid the price.

What is more, the messaging here has been extremely effective, drawing on scientific principles, bringing us together as a community and invoking powerful norms of mutual care to encourage us to act for the common good.

Fourth, the Scottish Government has, by and large, acted in partnership with the public, engaging in an ‘adult conversation’.

This has involved acknowledging mistakes, admitting limitations, being open about the situation and, above all, involving the public in the development of policy (both through traditional consultations and through new initiatives such as the digital platform).

Such a partnership is the basis of trust and buy-in to policies (after all, the best policies in the world are no good unless people actually abide by them).

And when it comes to the figures on trust in government leaders to deal with Covid-19, these are even more striking than the figures on deaths and infections.

As of the start of the month, Boris Johnson stood at an overall -40% rating while Nicola Sturgeon stood at +60%. I cannot recall seeing such a difference.

But the point of this contrast is not triumphalism. It is to learn from what works and what does not.

If we try to rub Westminster’s nose in its failures, it will only make them more reluctant to listen to lessons from Holyrood. And we need them to listen.

Because we all live together on a small island and the ability to deal with Covid-19 depends upon all the constituent nations coming together to pursue a common elimination strategy.

If there is one lesson we can all learn from what is going on in England and Scotland around the pandemic right now, it is that slow and steady does win the race.

Professor Stephen Reicher is a member of the UK Government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage) behavioural group and the Scottish Government’s Covid-19 advisory group.