Margaret Steel was a trailblazing woman in Victorian Fife – but one you’ve probably never heard of.

Quietly conquering gender stereotypes, Margaret was a plumber from Cupar in Fife.

While female plumbers remain uncommon, what makes Margaret’s profession even more unusual is that she lived during the Victorian era.

Margaret was born in Cupar in 1826 to John Glenday, a linen manufacturer, and his wife Isabella.

Although she grew up in the 1800s when there was a queen on the throne, the patriarchy very much reigned in the Victorian era.

Victorian domestic ideology

The ideology of ‘separate spheres’ based on gender biology was perpetuated during this time.

Men existed in the public sphere because they were seen as naturally strong; they pursued paid work and politics, and apparently distracted by sex.

On the other hand, women were viewed as weak and dependent, but morally superior with reproduction at the heart of their existence.

Therefore women existed in the private sphere, overseeing domestic duties and children, at home.

But poverty was rife, and this supposed ideal fell down in many working class families where women weren’t afforded the luxury of staying at home.

Lower working class women toiled in mills and factories, or worked in service, while middle-class women found ‘respectable’ skilled employment as drapers, milliners or seamstresses.

Drastic change in Margaret’s life

And in April 1861, the census shows 34-year-old Margaret was a skilled middle-class worker.

She was a dressmaker living in Bonnygate, Cupar, with her parents and her four sisters: Anne, Euphemia, Isabella and Jessie, who were all dressmakers.

Dressmaking was considered a decent way to make a living. It was clean, ladylike and showed that families had the money to pay their daughters to be apprenticed in the trade.

In 1961, Margaret married 29-year-old plumber Charles Steel at Bonnygate, Cupar, on October 31.

Like his late father before him, Charles was a plumber.

According to trade directories in 1861 and 1862, he was based at 16 Crossgate in Cupar where he owned a plumber’s workshop and house.

But 10 years later, the 1871 census shows a change in Margaret’s fortunes.

She is now a widow at the age of just 44, residing at the close at 16 Crossgate.

Margaret is listed as the head of the household, living with her younger sister-in-law Jane Ramsay Steel.

So far, so unremarkable.

How did Margaret go from pattern-cutting to plumbing?

But, while most other Victorian women on that census are listed as housekeepers or servants, perhaps milliners or drapers, Margaret is different.

Under the column ‘Rank, Profession or Occupation’, Margaret’s is given as ‘plumber’.

Not only is she a plumber, but she employs three men and two boys, with Jane as her assistant.

Sadly, Charles died less than three years into the couple’s marriage, on January 16 1864, aged just 31.

Their union bore no children and with Charles’ younger brother already deceased, it seemed there was nobody to carry on the family business.

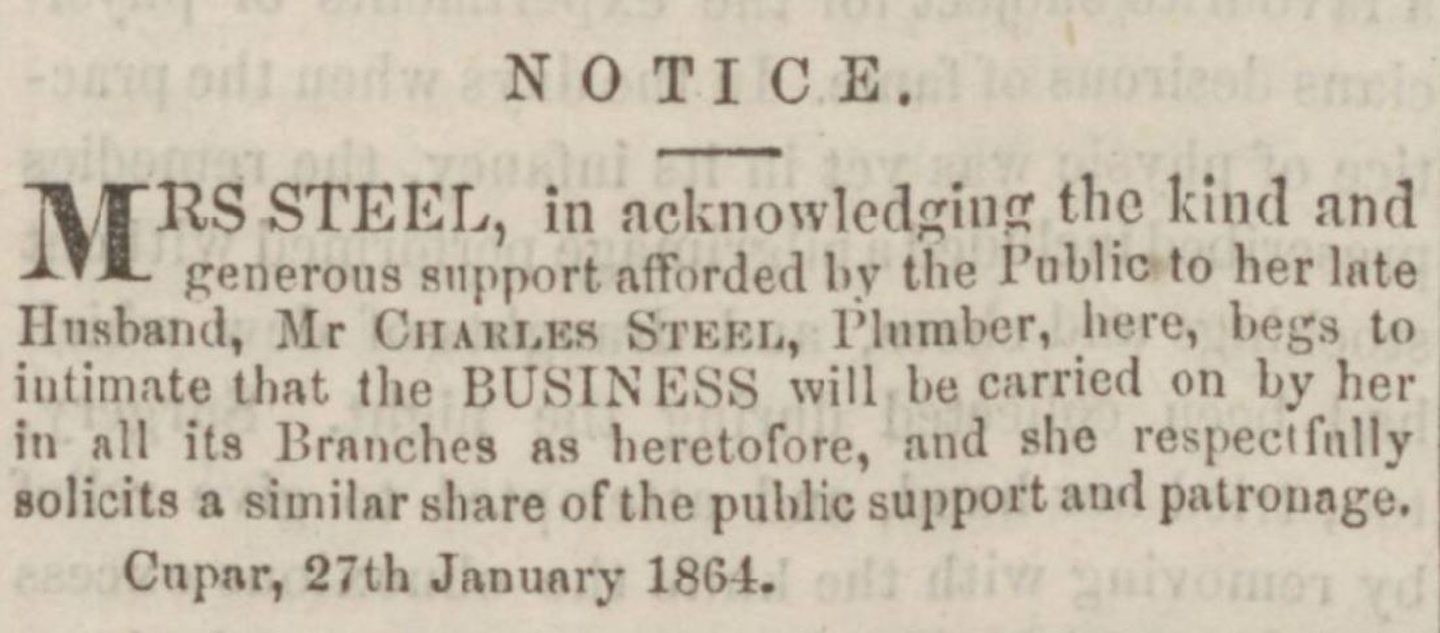

However, 11 days after Charles’ death, Margaret posted a curious advert in the local papers.

It read: “Mrs Steel, in acknowledging the kind and generous support afforded by the public to her late husband, Mr Charles Steel, plumber here, begs to intimate that the business will be carried on by her in all its branches as heretofore, and she respectfully solicits a similar share of the public support and patronage.”

By 1866, Margaret was listed in the trade directory as a plumber – an entry she would have organised and paid for herself.

The many skills of Margaret

Margaret made the bold decision to take on her husband’s plumbing business herself.

After marrying Charles, it’s unlikely Margaret continued dressmaking – she would have been expected to take on domestic duties in her own household.

However, it seems Margaret – who was a skilled and educated woman – had been helping her husband behind the scenes.

Although not apprenticed as a plumber, Margaret needed a good, working technical knowledge of the trade to successfully continue the business.

She may have become a plumber through marriage, but living at the business premises would have meant Margaret spent a lot of time in the workshop.

Whether familiarising herself with tools and their uses, or helping manage employees and balancing the books, Margaret would have gained a lot of hands-on experience.

Helped build Cupar landmark

As well as plumbing, her firm were bell-hangers, tinsmiths and gasfitters.

In the decade that followed, Margaret’s married name appeared in countless newspaper adverts citing building and plumbing contracts completed in the Cupar area.

Perhaps one of the most significant was the opening of the new St John’s and Dairsie United Parish Church in December 1866.

Under the list of contractors for the striking and commodious new church was ‘Mrs Steel, plumber, Cupar’.

Mrs Steel’s plumbing firm also carried out repairs to the manse and offices of Cupar Old Parish Church to the tune of £21 19s 14d.

Margaret successfully ran Steel & Co for 14 years until her death aged 48.

She passed away at 16 Crossgate on October 25 1874 from liver disease.

Although the name Steel & Co has gone, the family name lives on in Cupar’s heritage, as 16 Crossgate is known as Steele’s Close, a variation on the family name.

Conversation