A comic which put Dundee on the publishing map long before the Dandy and Beano celebrates its centenary this week.

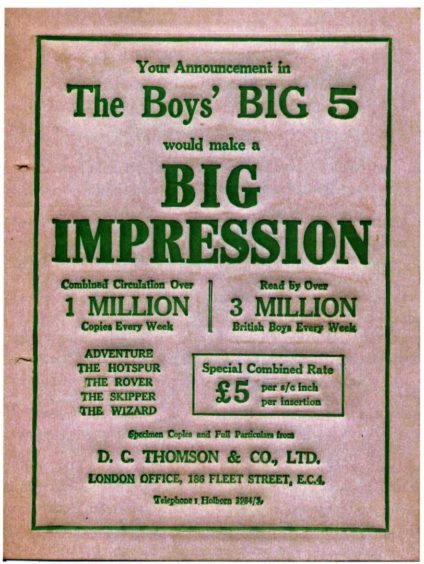

The success of the Adventure in 1921 led to the ‘Big Five’ – Adventure, Rover, Wizard, Skipper and Hotspur – which were eventually read by two of every three boys in the country.

In every playground

As DC Thomson’s company historian Dr Norman Watson points out, at one time there was probably not a school playground in the country in which a Dundee comic was not being passed around.

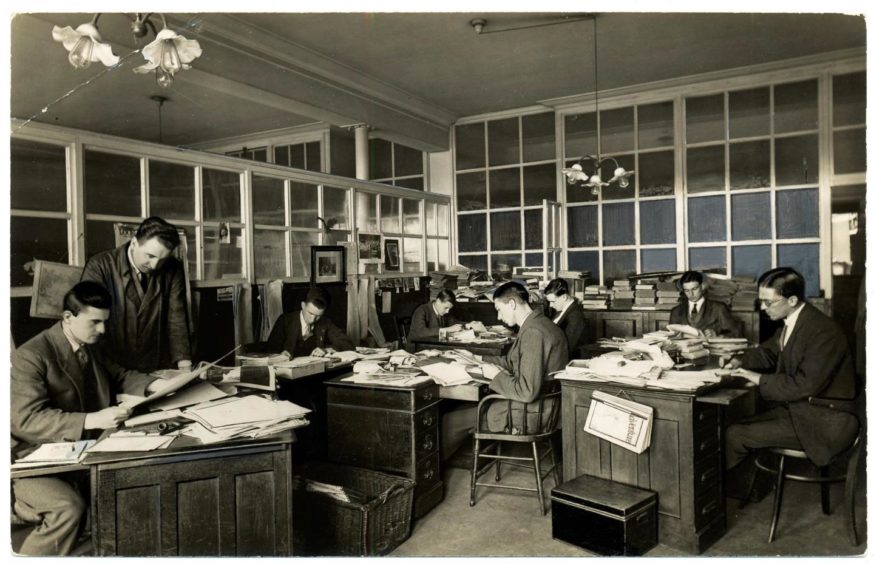

The launch of DC Thomson’s boys’ papers in September 1921 led to the creation of a new department on the second floor of the firm’s Albert Square headquarters in the centre of Dundee.

Back in the 1920s, ‘Meadowside’ – as the building was known – bore no relation to today’s wondrous open-plan office space.

It was filled with a rabbit-warren of small offices, each with a half-glass partition separating it from the corridor and neighbouring offices.

Inside each was an open fireplace.

Desks and chairs were wooden. Some rooms had fireproof safes, while others had walk-in cupboards for company business records.

The hanging lampshades, however, were invariably smashed by rolled-up ‘footballs’ of rubber bands.

Paper was everywhere – recycled ‘bumff’ pads for creative scribbling, proof copies hanging by chains, cabinets for scripts, cupboards for artwork, maps on the wall and shelves of books for artists’ references.

Pens and pencils sat in upturned gum tins.

Editorial staff, senior and junior, dressed smartly and good timekeeping was expected and encouraged.

And everybody looked out over Dundee High School or the ancient Howff cemetery.

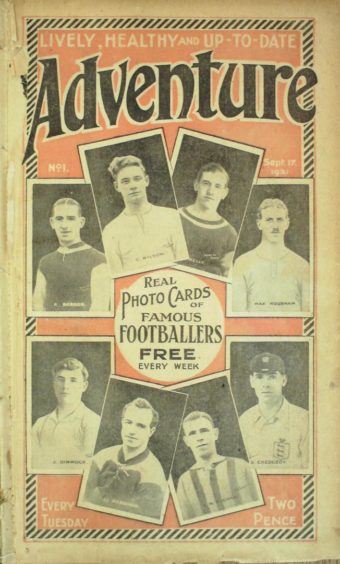

Here, on 17 September 1921, DC Thomson issued a boys’ paper which launched one of the most famous series of titles in children’s publishing history.

Adventure, a brilliant mix of all-action text stories, was the first in the so-called ‘Boys’ Big Five’.

The Thomson family’s resolve to push on with this juvenile departure from its well-established newspaper business was supported by events.

Firstly, war returnees had created a pool of spare staff at Meadowside and they had to be found jobs.

Over 400 DC Thomson-related personnel – journalists, artists, etchers, office staff, linotype operators, compositors and printers – had joined the Services, more than from any other publishing house outside London.

‘Managing proprietor’ David Couper Thomson saw the war for himself in 1917.

Too old to serve at 56, he described to Courier readers the experience of shell fire after a hair-raising drive to the Western Front in an open-topped Daimler.

Secondly, wartime paper and ink rationing and agreements to limit circulations had acted to dampen expansion.

Come the 1920s, there was spare capacity in the presshalls on the ground floor at Meadowside, and at the firm’s other print centres in Glasgow and Manchester.

Technically, the production of a new comic was made possible by the addition at this time of an additional fold to tabloid-size newspapers, by a device known as a pony folder.

This was key to the firm’s development of the children’s market between the wars.

Thirdly, rival London publishers had attracted big sales from experimental comics in the early years of the century.

In particular, Adventure was issued as a response to the success of Gem (1907) and Magnet (1908), popular boys’ story weeklies published by Amalgamated Press of London.

In the summer of 1921, David Grimmond was transferred from the Dixon Hawke Libraries to become Adventure’s founding editor, with Stewart Gilchrist as his chief sub-editor.

The staff settled in and Harold Thomson, David Couper Thomson’s nephew, was able to report on 19 July 1921, “I think Mr Grimmond is getting on pretty well and we should have the paper made up and in proof form within a day or two.”

Despite a postponement due to technical problems with the cover gift of football photographs supplied by Cardigan Press in Leeds, Adventure got off to a blistering start.

After the dust had settled on its opening issue, a delighted Harold Thomson wrote to his London Office manager: “We issued 220,000 Adventure last week and were unable to execute quite a lot of orders.

“This week the number is 279,000 and we are now sold out.”

The new paper was a runaway success.

Cost 2d, came out on Tuesdays

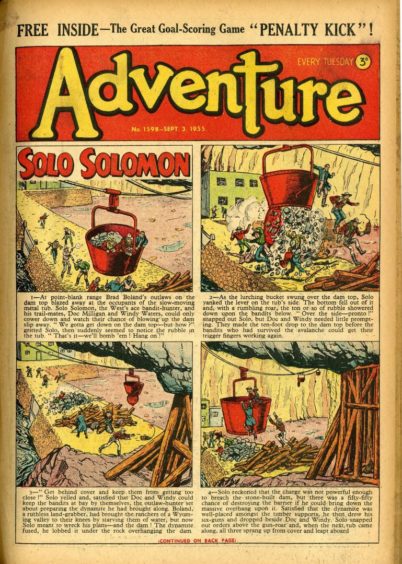

Adventure had 28 pages and was the standard 11in x 15in ‘comic’ size. It cost 2d and came out on Tuesdays.

It was filled with six or seven fiction stories, a jokes page and often a competition.

Tales included The Wireless Kid and Non-Stop Ned, the dashing motorist.

Ace detective Dixon Hawke transitioned to the paper and, by mid-decade, the now-famous comic artist Dudley D. Watkins was illustrating text stories and serials for the paper.

Watkins’ work for Adventure included his first regular comic strip, Percy Vere and His Trying Tricks, about an inept magician.

Come the 1950s, he completed a unique comic achievement when he drew Biffo the Bear for the front cover of Beano, Mickey the Monkey for the front of Topper, and Ginger for the front of Beezer… not to mention Oor Wullie and The Broons for the Sunday Post!

Adventure’s first issue carried the topline ‘Lively, Healthy and Up-to-Date’ and its ripping yarns soon edged out its rivals.

While Magnet and Gem dwelled almost exclusively on school stories, Adventure lived up to its name; covering sport, war, exploration, science fiction – anything with thrills and spills.

And boys (and their sisters) could not get enough of it.

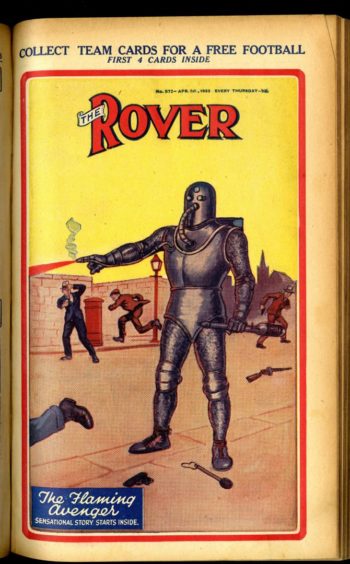

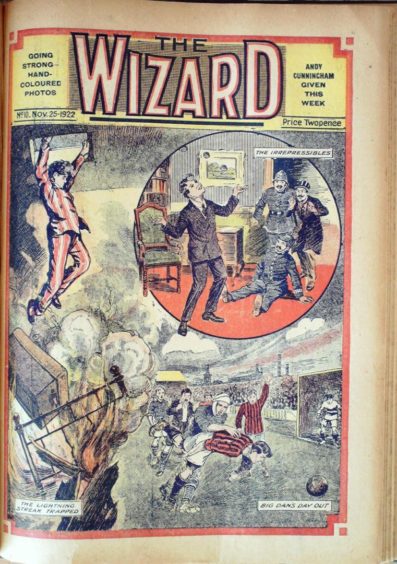

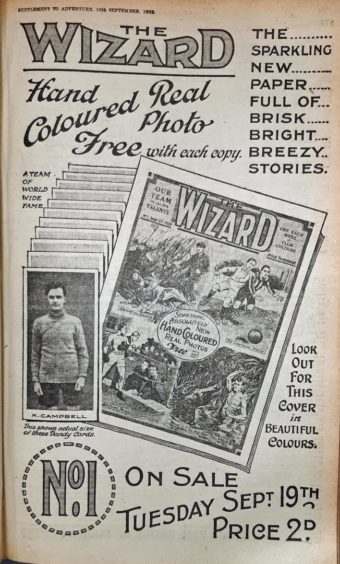

Adventure is celebrated today as DC Thomson’s first boys’ ‘comic’ – but before a year had passed, further second floor offices were required when Rover and Wizard were launched in March and September 1922 under the guiding hands of R. D. ‘Bert’ Low and Fred Tait respectively.

Robert D. Low is often credited as the creative genius behind the Big Five.

In 1922, however, he was still a young man who had recently joined the juvenile department.

The editorial direction came from David Couper Thomson and his nephew Harold, and it was Harold, with a journalist’s instinct that never left him, who realised that the first boys’ papers had to be different, adventurous and thrilling.

“It’s the matter in the paper…”

When Rover No 1 was issued in 1922 with a huge launch run of 374,517 copies, on its way to smashing Amalgamated Press’s monopoly of the boys’ market, it was Harold who could tell founding editor Low, “Remember, it is the matter in the paper that really counts.”

The first issues of Rover were printed in Glasgow, which required a special delivery of 130 tons of paper, carried on the SS Cremona from Gothenburg.

Pages for the first issue went to press on February 7 and it appeared for sale on March 2.

Over three columns of tightly-set text, Rover introduced the working-class heroes Alf Tupper, the Tough of the Track, and the Second World War flying ace Matt Braddock.

Both Tupper and Braddock were the creations of Low’s chief sub-editor Bill Blain, whose creative antennae shaped a stream of classic characters and plots.

Blain eventually led the Wizard for 20 years, during which time he also created Wilson the Wonder Athlete and the Wolf of Kabul.

By May 1922, the combined sales figure for Adventure and Rover was an astonishing 848,000 copies weekly.

The new titles were a triumph for the company and thoughts quickly turned to expanding the department.

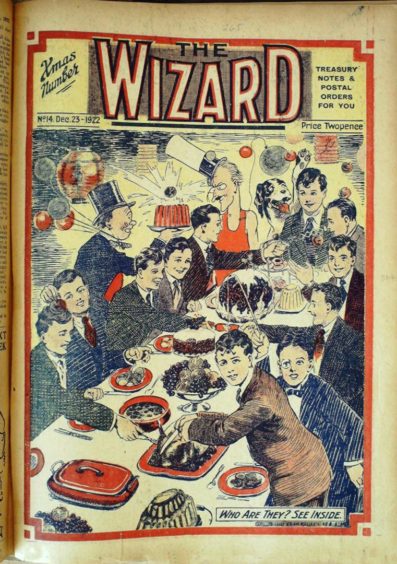

Next came the Wizard, which appeared on September 23, 1922.

Launches in the autumn as the days grew darker

This time the initial print was split – with 100,000 planned for Glasgow and the bulk, between 350,000 and 400,000, from Manchester’s four presses.

Launches frequently took place in the autumn, timed to take advantage of darkening evenings during pre-television days.

Wizard came out on Saturdays.

This allowed the trio of titles to begin a rotation of ‘house’ adverts to encourage boys to try Adventure on Tuesdays, the Rover on Thursdays and the Wizard at the weekend.

The new paper reached a circulation high of 467,518 in March 1950.

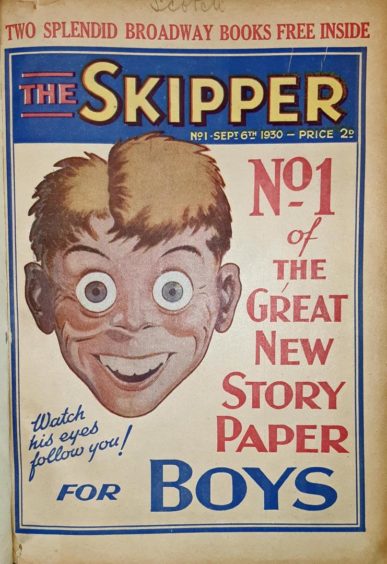

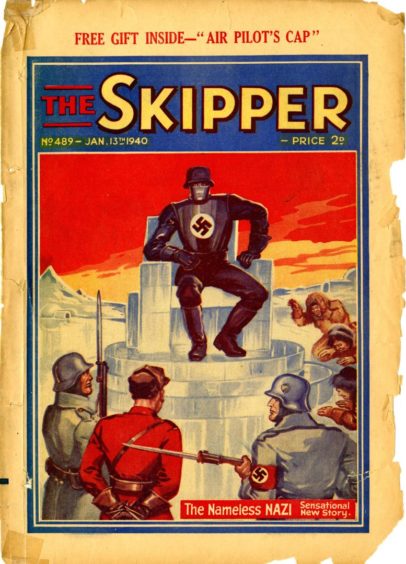

The Skipper, the fourth of the Big Five, arrived on September 6, 1930, edited by R. D. Low.

The new title had few mainstream characters during its short run, but regulars included cowboy Red Rock Baxter, Napper the Scrapper and Wembley Bill, the Football Doctor.

The Harry Potter idea of invisibility was as popular then as it is today.

In 1922, Rover introduced Invisible Dick, the boy who could disappear at will.

With a less beguiling title, Skipper conjured up its own vanishing character in the bow-tied Puck McLean.

Skipper was discontinued after 543 issues on February 1, 1941, by which time its circulation had fallen to 160,000.

Its suspension was due to paper and ink rationing, and wartime staff shortages across the second-floor titles.

More wartime restrictions

Meanwhile, the Adventure’s 1000th issue appeared on December 28, 1940, by which time war restrictions had seen the paper reduced to 18 pages.

As the conflict continued, it was further reduced to 14 pages and issued fortnightly. Weekly publication did not resume until April 1949.

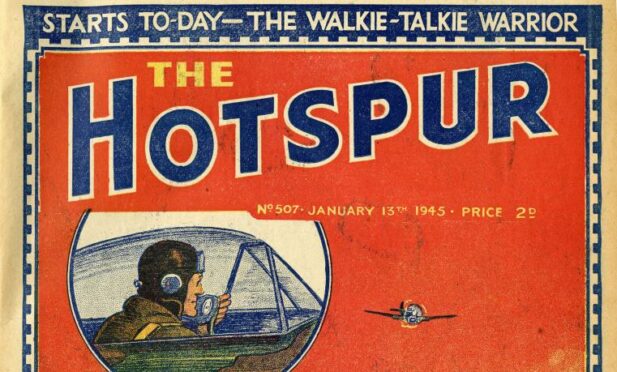

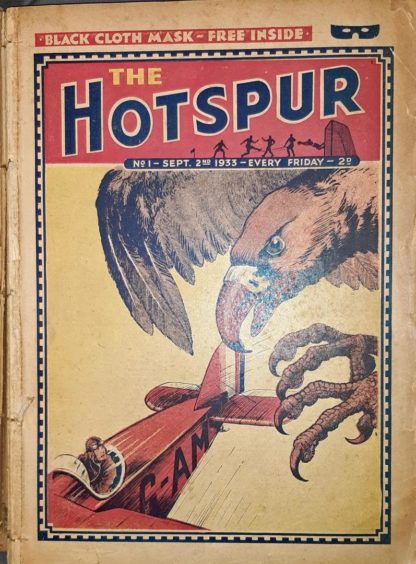

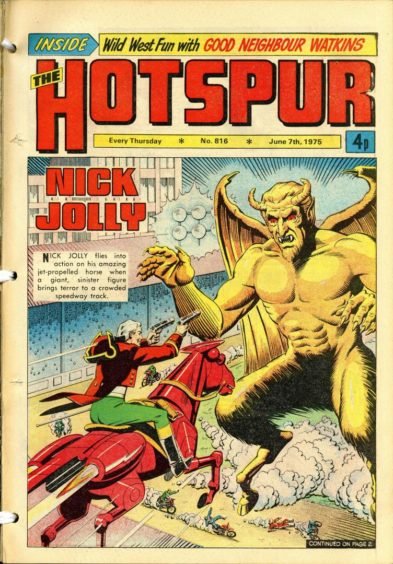

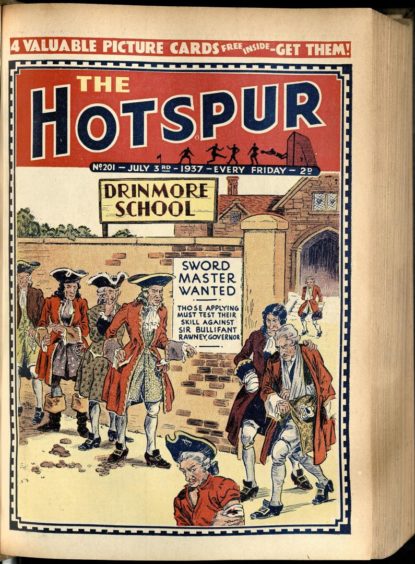

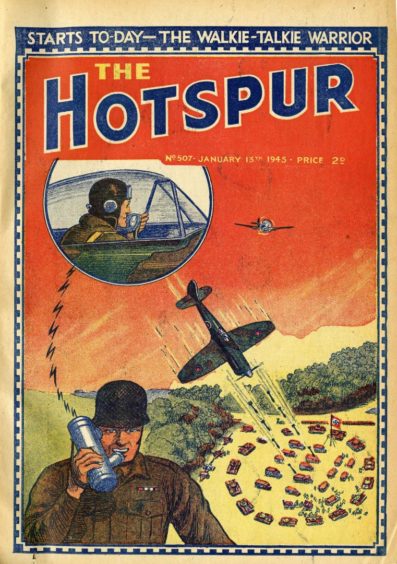

Next from the Second Floor came one of the most famous and enduring boys’ ‘comics’ of all – the Hotspur.

Launched on Fridays with an impressive run of 344,000 for its first issue on September 2, 1933, Hotspur followed the by-then familiar and successful ‘action story’ template; letterpress printing, 11in x 15in format, colour covers and the innocent escapism of seven or eight text stories or serials surmounted by a title and illustration.

The paper was initially filled with school-related tales (the only one of the Big Five to do so), but gradually expanded to include adventure, detective, science fiction and war stories, with its fair share of giant monsters, robots and extra-terrestrials.

Top characters included the superhuman runner Wilson, who had previously appeared in the Wizard, Braddock of the Bombers from the Rover, who later proved popular in Victor, and Union Jack Jackson, who subsequently battled through series after series in Warlord.

Five million newspapers and magazines a week

When Hotspur hit the streets in 1933, DC Thomson had 1700 staff in Dundee and major offices in Glasgow, Manchester and London.

It was printing five million newspapers and magazines every week, requiring 300,000 miles of paper annually and 600,000 lbs of ink.

In other words, in just 50 years it had evolved from a two-newspaper partnership run by a trio of brothers into a major UK publisher with a stable of daily, weekly and Sunday newspapers, women’s magazines and, of course, the Boys’ Big Five.

And, by the 1940s, around 2.4 million boys read the titles – two out of every three in the country.

Tide begins to turn

But the tide was on the turn. Most of the boys’ papers declined in popularity after the Second World War, due in part to the growth of television, the appearance of the million-selling Eagle in 1950, and the falling population of young people across Britain.

The final copy of Adventure was dated January 14, 1961 and numbered 1878.

The following week it merged with Rover and became Rover & Adventure.

This title survived until October 1963, when the title reverted to Rover.

The DC Thomson ‘Fun Factory’

But as the boys’ papers began their slow decline, the DC Thomson ‘Fun Factory’ – its creative and mischievous ‘Second Floor’ – continued to champion children’s publishing through household-name comics such as Dandy, Beano, Topper, Beezer, Sparky, Buzz, Cracker and Nutty, winning a huge new audience of youngsters.

Through their stories and characters, generations of children have come to realise the pleasure gained from reading, often leading to a lifetime’s love for, and interest in, the written word.