My own memories of wandering into the National Galleries of Scotland’s (NGS) Scottish collection on The Mound as a history of art student in Edinburgh many moons ago include descending a ramp into a dark, windowless space where great works felt as if they’d been forgotten by the world above.

But now this is no longer the case, thanks to the opening of a suite of new gallery spaces which house over 130 key works from the NGS’s Scottish art collection.

The works date from around 1800 to 1945 and artists include William McTaggart, Anne Redpath, Phoebe Anna Traquair and Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Offering more than double the display space than before, the artworks can be accessed via the gallery’s East Princes Street Gardens entrance. The addition of large windows not only brightens the once dim spaces, but also offer impressive views of Scotland’s capital.

Curator Freya Spoor says that much effort has gone into perfecting the spaces for visitors: “We’ve devoted this time to making the new galleries, getting that right and creating this new light, spacious feel so that the artworks can be shown to their best advantage.”

Research showed fewer than 20% of visitors ever made it to the Scottish galleries – also known by staff as the basement wing, or B wing, with its 1970s brown carpet and fluorescent lighting.

Freya explains: “It was quite a dark space and the use of walls to divide the space and create small pockets gave it quite a claustrophobic feel. You couldn’t really stand back and enjoy the artworks.” She goes on: “I can guarantee people will see these works in a completely different way. It’s a much more immersive experience.”

Scottish art can be bold and colourful

Freya says there is a common misconception that Scottish art in the collection is a lot of dark brown paintings that don’t have a huge amount of relevance, but this couldn’t be further from the truth. “There’s lots of colour, it’s bold and there are some fascinating stories about how these were made, what they depict and what goes into and speaks to Scottish history, culture and who we are as a nation.”

And there are a number of artists with connections to the local area that may be of interest to those wishing to see the new galleries for themselves. Until recently, Perth boasted an art gallery dedicated to the work of Scottish Colourist John Duncan Fergusson and his wife, the dancer and choreographer Margaret Morris.

As part of a major project to create a museum in the former city halls and transform the existing museum into Perth Art Gallery, the Fergusson Gallery is now closed. There are, however, plans to introduce dedicated displays of the collection to the art gallery next year.

Scottish Colourists at Scotland’s National Galleries

“It’s an incredible collection and we are lucky to showcase just a few examples of his paintings alongside some of his colleagues in the Scottish Colourists,” Freya says. Works include: Portrait of Anne Estelle Rice (1908), brass sculpture Eastre (Hymn to the Sun) (1924), and In the Patio: Margaret Morris (1925).

“Morris was an incredible artist, dancer, businesswoman, entrepreneur – and In the Patio dates from a period in the 1920s when the couple were living in the south of France and they had people like Ernest Hemingway coming for tea. It was quite incredible the lives they led.”

Going back further are works by 19th Century painters Robert Herdman, who was born in Blairgowrie, and George Paul Chalmers, born in Montrose. Both were students of Robert Scott Lauder.

“Lauder encouraged his students to be quite individualistic and thought it stifling to creativity to have a very rigid system. He was much freer in his approach and I think that led to a golden generation of Scottish artists who were massively different,” Freya reveals.

Herdman was known for his dramatic and emotive depictions of themes from Scottish history – such as Mary, Queen of Scots: The Farewell to France (1867) – meanwhile, Chalmers was known for countryside scenes and cottage interiors and The Legend (c.1864) depicts a group of children listening to a woman telling an epic tale.

Their teacher Robert Scott Lauder was best known for his subject pictures, often based on the works of Scots author Sir Walter Scott. His work The Gow Chrom Reluctantly Conducting the Glee Maiden to a Place of Safety (1846) is taken from a scene in the novel The Fair Maid of Perth.

Art school in Dundee opened

Freya explains that artists such as Herdman and Chalmers had no choice but to travel to cities like Edinburgh or Glasgow to study art because there was nowhere closer to home. As the 19th Century went on, however, there were concerted efforts to establish art schools in places like Dundee, which would eventually culminate in the city’s now renowned Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design.

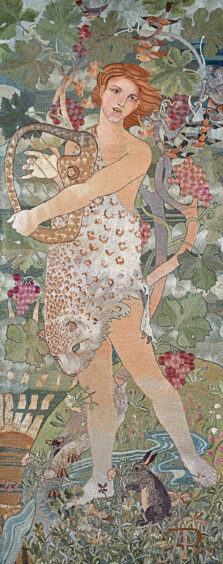

The full-time art school opened in 1888 with the Dundee Technical Institute followed by the appointment in 1892 of the first full-time drawing master, Thomas Delgaty Dunn. “That’s when you find a new generation – when there’s that local investment. One of the key people within that cohort was John Duncan, who was a key cornerstone of the Celtic revival movement alongside Phoebe Anna Traquair,” Freya says.

Born in 1866, Duncan grew up in Dundee’s Hilltown area and studied art at evening classes, finding work as an assistant in the art department of the Dundee Advertiser newspaper (which would go on to merge with The Courier in 1926). He studied elsewhere, but returned to Dundee in 1889 and became one of the founding members of the Graphic Arts Association which is now the Dundee Art Society. He also took up a teaching post in the city.

Duncan’s work Saint Bride (1913) depicts the Irish saint as she was miraculously transported to Bethlehem to attend the nativity of Christ. Freya says he was particularly proud of this work as he reportedly painted himself into it in the guise of a small character called the holy fool.

Another artist who benefited from the founding of Dundee Art Society was Beatrice Huntington, who was born in St Andrews. “She went to study art in Paris (as well as the cello in Austria) and took up a role as an illustrator in London during the First World War,” Freya explains.

“After this, she moved back to St Andrews and exhibited at the Dundee Art Society. She met her future husband – Dundonian landscape painter William Macdonald – and the couple were close friends of the Scottish Colourists.” In 2019 the NGS acquired her painting, A Mulateer from Andalucia (c.1923) which shows the influence of the Cubism movement.

“It’s displayed very close to JD Fergusson and FCB Cadell, so these connections show she was part of that same group of artists who were embracing Scottish art ideas.”

There’s also a work by Dundonian painter James McIntosh Patrick – Stobo Kirk (1939) – which has been lent from a private collection. “He is most celebrated for his landscapes of Dundee and Angus and he joined the staff of Dundee’s art school in 1929,” Freya says. “This work belongs to a group he made in the late 1930s and he did a number of versions of this 12th Century church near Peebles. Each time, he would rework it and change something.”

Wider idea of Scottishness

Freya adds that while the collection is titled the “Scottish” galleries, they have taken a wider idea of Scottishness, including works by artists who have made a substantial contribution to the history of the country’s art.

One such artist is English painter Sir Edwin Landseer, who first visited Scotland in 1824 and returned almost annually. Freya says his pictures of Scottish subjects were a phenomenon that got people interested in visiting.

His well-known work The Monarch of the Glen (1851) which depicts a “royal” or twelve-point stag surveying a Highland landscape, was acquired by the gallery in 2017 and has been relocated to the new space from its spot in the upper galleries.

“This image has essentially travelled the world. People know it, but when they see it for the first time, they’re always surprised about how big it is, or the format and the quality of it. Some people love it and some people hate it – but they still come to see it.”

Art can be a cause for debate

Freya adds that good art should be a cause for debate: what makes it exceptional, why could it be potentially problematic and what does it say about the society in which it was created?

“Something like The Monarch of the Glen has the potential to spark a lot of conversations, and that’s what we want,” she goes on. “Art needs the audience and the visitors to bring it to life. Museum collections are not staid or frozen in time – they’re always interacting with the people who come to see them.”

- The Scottish galleries are located within the National on The Mound in Edinburgh. Admission is free. See nationalgalleries.org