Ahead of new Sound Stage monologues ‘Blaccine: First Dose’ at Pitlochry Festival Theatre, Michael Alexander speaks to writer Maheni Arthur about her experiences.

When the first Covid-19 vaccines were approved for use in the UK back in December 2020, the message from government and the NHS was clear – vaccines are the most effective way to prevent infectious diseases.

However, as the roll-out continued, media reports began to emerge that people from black or black British backgrounds were less likely to get the vaccine.

Studies began to suggest that lower Covid-19 vaccine uptake among black ethnic groups in London compared to white British groups was driven by trust, including mistrust in the vaccine itself and in authorities administering it.

But were the reports accurate? And if so, why? With vaccine sceptics also existing amongst a lesser proportion of the white population, and as the NHS tried to quash “disinformation” about the vaccines, was racism an underlying issue?

Challenging the rhetoric

One man intrigued to know more was Tonderai Munyevu, an award-winning writer and director for theatre, screen and radio, who was born in Zimbabwe and raised in London.

In 2021, he read an article that said black people in the UK weren’t taking the Covid-19 vaccine.

It was presented as a “hard and fast fact”.

He felt like someone was telling the story of black individuals in the UK rather than it actually being real.

Tonderai (Mugabe, My Dad and Me, winner of the Best New Play at the UK Theatre Awards 2022) wanted to interrogate the issues and understand why.

He went to London-based theatre company Stockroom with the idea of doing a piece.

The result is a new Pitlochry Festival Theatre Sound Stage audio production Blaccine: First Dose, which investigates the black British community’s relationship with the Covid-19 vaccine.

Featuring three new monologues written by Tonderai Munyevu, Maheni Arthur and Isaac Tomiczek, the new Pitlochry Festival Theatre and Stockroom production in association with Naked Productions, will be broadcast on January 12,19 and 26.

‘Surprise’ at findings

Speaking with The Courier from London, one of the writers, poet Maheni Arthur, explained how the more research they did, the more they were “kind of originally surprised by the reality”.

“I know from some of the interviews we did that black people weren’t taking the vaccine,” she said.

“But the real story that started to come out was ‘why is that then’?

“Our work became something that was still about the Covid-19 vaccine but more about black people concerned about their place in this country.

“We were speaking about medical racism and why maybe black people would be a bit more hesitant to put themselves in a medical situation.

“We really started to get these stories of people who had been mistreated or dismissed or overlooked and we wanted to bring some respect to those stories, because that’s real.

“It was really shocking and upsetting and surprising to hear.”

Pre-Covid-19 experiences

With the research interviews carried out in Brixton, south London, Maheni gave examples of pre-Covid-19 stories whereby black people they spoke to had been “misdiagnosed or completely overlooked for treatment” for “reasons not really known”.

Someone’s mum for example, was having a “certain type of pain” and going to the doctor and was basically told “it’s nothing or you don’t need treatment or it’ll go away on its own”. In some cases, the conditions got progressively worse.

Asked why she thought this was, Maheni said: “I know that in medical history black people are commonly looked at sometimes as not feeling as much pain as their white counterparts which is something that stems from years back – slavery times.

“I feel like it stems from a thing of black people not being believed, or even black mothers in childbirth less likely to get a certain kind of help depending on the pain that they feel, and that comes from people seeing blackness as a ‘less than’.

“That came up a lot – a lot of people being dismissed for treatment and things progressively getting worse.

“It kind of goes down to how we are seen as individuals and the unconscious biases that people have.”

Maheni said she thinks it’s “sometimes” – although not always – racism that’s the problem.

Racism is a word, she said, that immediately makes people feel “uncomfortable”.

A lot of this, she feels, is “unconscious bias” – because everyone carries prejudices in their minds.

She feels it stems from “years and years of conditioning and lack of representation and social inequality”.

The experiences relayed by interviewees are very real experiences and it’s important to respect that, even if understanding the reasons is not clear.

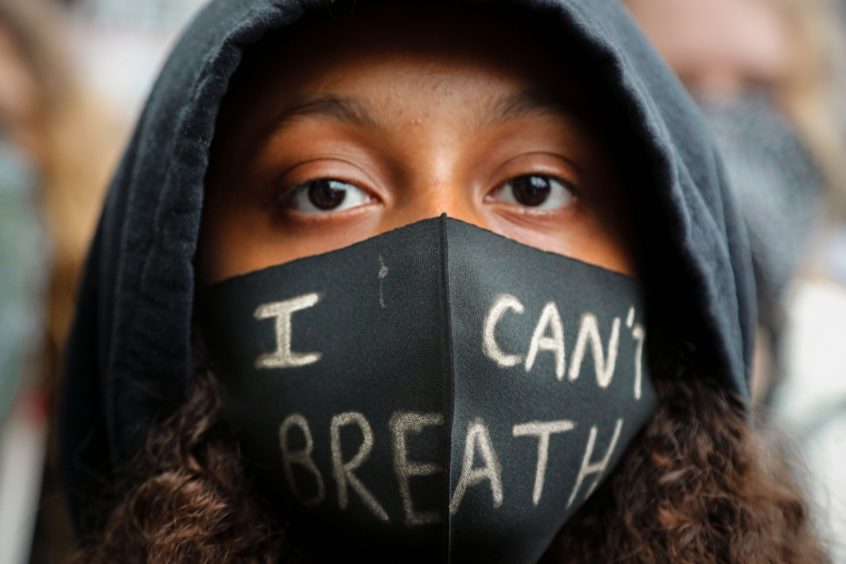

Another important issue to consider, however, is that the Covid-19 vaccine roll-out coincided with the Black Lives Matter protests and the fallout from the killing of George Floyd in the USA.

Black Lives Matter impact

Maheni said: “I think what happened with the Black Lives Matter protests is it made people wake up and kind of look at things head on.

“I think a lot of people had to have some really uncomfortable conversations with themselves and think about their biases.

“As difficult as it was, I think it did something really important that was to bring a lot of things to the forefront that people would rather not speak about.

“It matters that all of that happened at the same time.

“I wonder how it would have been different if the George Floyd protests for example had happened a year before or a year after?

“It’s interesting that all of those things were happening at the same time and we had to grapple with our mortality as a society and as a country and stuff, and black people having to face the reality of their mortality as well.

“For me, when I think back to that period, it was terrifying. It was scary. It felt really isolating. It also felt really exposing because of what happened to George Floyd and all the protests.

“Suddenly everyone was talking about the same thing – white supremacy, everyone is talking about whiteness and blackness and what it means and what we can do.

“I was on social media a lot because I was scrambling for that connection that we couldn’t have physically (during lockdown).

“It felt like people were kind of finally understanding a little bit of what it’s like to experience that as a black person regularly.

“That’s the one word that comes to mind – that it was really exposing.

“I think it was a good thing that the conversation happened.

“But it was difficult especially when you are toeing that line of ‘I want to know what’s going on and be informed and I want to help people understand themselves’ but also I just wanted to run away from the whole thing. It was hard.”

‘Releasing the pain’ through writing

Maheni, who ran a cocktail bar before Covid-19, found a lot of strength and support from doing the project.

With Shockroom her first professional writing job, she found writing the monologue “quite healing”. She had to dredge up a lot of difficult memories from 2020.

But the writing of it became quite cathartic and “finally released the pain” she’d been feeling.

Maheni added: “I really just want people to listen and understand that these are pieces of writing that are based on personal experiences.

“We are real people. We are not just writers who have written a monologue out of thin air.

“I also want people to understand that while yes it’s a play it’s still going to be uplifting and heart-warming and funny in parts – it’s not all doom and gloom!

“We really want to be heard.

“We also want to spark a little bit of conversation and maybe like a bit of introspection.

“I also really hope that the black people who are listening can feel seen and heard in their own way as well.”

Academic evidence backs racism claims

Evidence of racism being an issue in the vaccine roll-out grew before Christmas when a briefing published by the Runnymede Trust and The University of Manchester’s Centre on the Dynamics of Ethnicity backed the concerns.

It concluded that racism was the “fundamental cause” of Covid-19 vaccination hesitancy among ethnic minority groups.

The authors of the new briefing argue that by the time people were deciding whether to have the vaccine, the conditions that created lower vaccination uptake among ethnic minority groups were already present.

By ignoring the impact of structural and institutional racism on vaccination rates, “vaccine hesitancy” is misunderstood – and crucially, the opportunity to address inequities is missed.

The briefing used data from the UK Household Longitudinal Study to show that institutional and community-level factors, driven by structural and institutional racism explain the large majority of ethnic inequities in vaccination rates.

Vaccination hesitancy rates vary across ethnic groups, with over half of the black group reporting hesitance to get the Covid-19 vaccine, compared with just over 10% of the white British group.

How and when to access Blaccine: First Dose

Blaccine: First Dose will be broadcast on Sound Stage on Thursday January 12, 19 and 26 at 7pm. For further information and to book tickets visit www.pitlochryfestivaltheatre.com

Every performance will be accompanied by a post-show event, hosted online, inviting audiences to engage further.

Conversation