For Chris Duffy (54) the purchase of a second-hand cookbook for the bargain price of two pence was the beginning of a life-long love for cooking and food related memorabilia that he has brought together in the Auchtermuchty Food Museum.

According to the former actor and puppeteer, who moved to Fife from London more than 30 years ago, Chris’s childhood memories don’t include much delicious home-cooking; “My mum couldn’t cook and had no interest in cooking,” he recalls, “My sisters and I were reluctant eaters. Mum told us that we could like it, lump it or cook it ourselves.

“So I tried doing it myself. Initially I cooked from packets, things like boil in the bag cod in butter sauce and crème caramel (it was the late 70s!), but eventually I bought a second-hand book (Wholefood Cookery, 2p) from a local shop and tried some recipes. My early attempts weren’t great, but I really enjoyed the process of reading and deciphering a recipe and then cooking and serving a meal. The pleasure of that has never left me. Once I’d cooked my way through that book I got another, and by the third or fourth book I was hooked.”

Chris, who is now married with two grown-up children, worked in theatre and television for many years before moving into venue management. His early, practical interest in learning to cook soon developed into a fascination with the books themselves, as he explains: “I stumbled upon Paris Bistro Cookery/The Art of Simple French Cookery by Alexander Watt very early on (I think it was the second book I bought) It was two books in one, in an almost dos-à-dos binding. It was the first book I enjoyed both for its contents and as an object.”

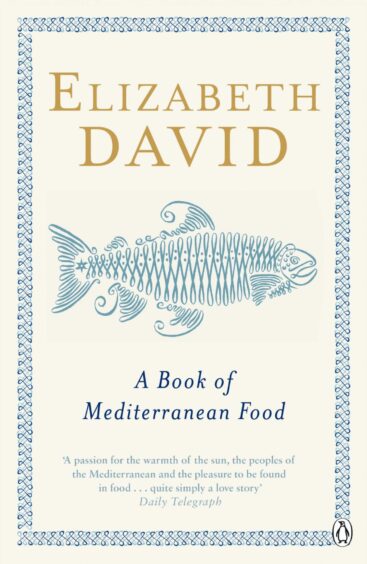

Next up was a gift of the iconic Elizabeth David’s Book of Mediterranean Food from a friend and the realisation that cookery books could also be a source of entertainment and information over and above the recipes they contained. “I enjoyed Elizabeth David’s books for their stories and recipes,” says Chris, “but she would write about authors she admired or who had influenced her and so through her I discovered people like Jane Grigson, Xavier Marcel Boulestin and Edward Pomaine.

“Slowly, the books became a collection, but those early discoveries are all still there and I enjoy reading and using them still. Marcel Boulestin became a bit of an obsession and I’ve spent years hunting down his books – I’ve even got a copper stock pot from his first London restaurant. To me, a treasure!”

First of all, he concentrated on buying books but his horizons soon widened to include; “all sorts of items; books, manuscripts, artworks, photographs and documentary objects/artefacts. I’m always actively collecting and buy through traditional and online auctions, from dealers in various disciplines, other collectors, but I still love a rummage in a bookshop or junkshop where you don’t know what you’re looking for until you find it.

“People also donate items and I love the opportunity to understand and preserve the family story and provenance of an item. Anyone who collects anything will recognise that thrill of the chase. Those who don’t, won’t.”

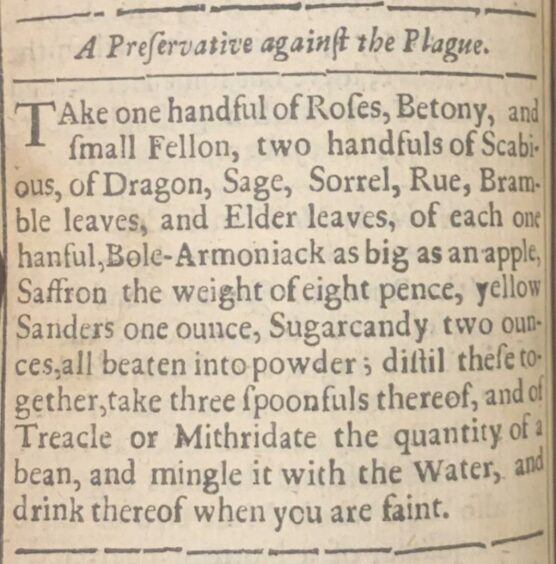

The collection at The Auchtermuchty Food Museum has no strict parameters but there are some subjects that Chris finds himself drawn to again and again. “I still seek out antiquarian cookbooks,” he says, “I particularly like herbals and books of secrets that often contain a mix of medicine/health/diet and strange snake oil like remedies and advice.

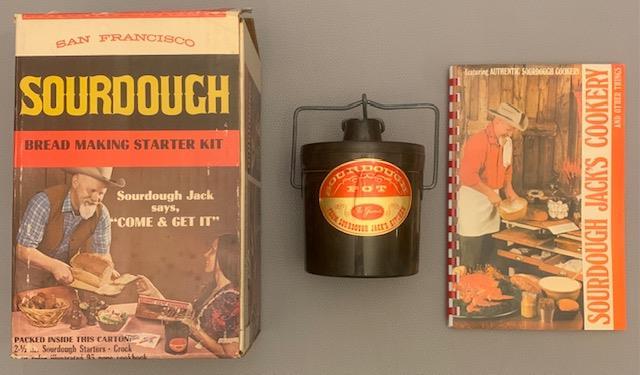

“I love kitsch cookbooks too, which, when I started collecting them were pretty much disregarded, but are very popular now. Fanny Cradock is perhaps the embodiment of this type of cooking; classical principals but reimagined for the home cook with colour and embellishment, mostly for ‘show.’ Her archive is in the collection and items from it always create interest when they are part of an exhibit.”

He hasn’t totally left his love for performance behind and admits that; “because of my background in theatre I’m drawn to ‘famous’ food and have some items with interesting connections to theatre and entertainment either in their creation or through their provenance.

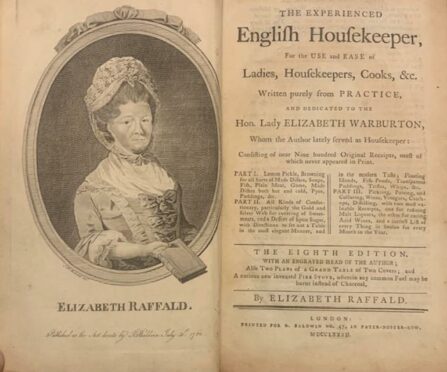

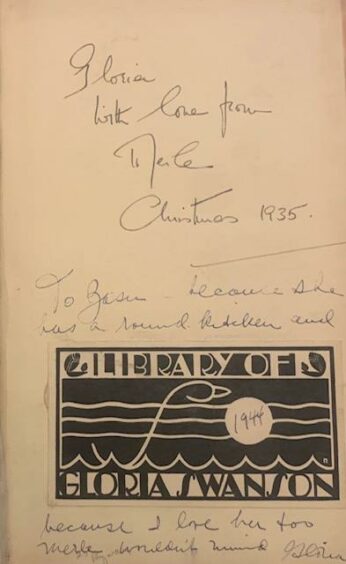

“A good example of this is our copy of The Experienced English Housewife, by Elizabeth Raffald, who was a very enterprising businesswoman writing in the 18th Century. The copy of her book is a good antiquarian item but not extraordinary, except for it’s provenance. It was given by Merle Oberon (Wuthering Heights) to Gloria Swanson (Sunset Boulevard). Gloria then passed it on to ZaSu Pitts (Greed, It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World) and her gift inscription mentions ZaSu’s new, fabulous ‘round’ kitchen.

“The number of stories you can tell from a single volume like this I find very exciting,” enthuses Chris, “As well as telling stories about food, food history and society, the collection itself is a personal expression.”

For Chris, the idea that food is central to life is a fascinating concept that every person shares and while enormous changes in terms of what and how we eat have taken place, one thing had always been apparent: “Technology and fashion can all influence what we eat and how. And who gets to eat what. The rich get to choose, the poor don’t.”

And of course there are some foods and recipes that will always stay with us, “I find it quite reassuring to read a recipe for something that was written a few hundred years ago and recognise the ingredients and method as something that feels ‘modern’.”

“Food is a very interesting way to travel through history. Sometimes it is part of the story and often it is the story. It can tell very important or moving stories and sometimes the objects in the collection help us remember something light, humorous, and ephemeral. I find that variety very compelling and it is one of the things that keeps me dedicated to developing the collection – you see and feel stories developing.”

Focusing on cookbooks alone won’t give us a full picture of what people were actually eating at a particular time, though. “Cookbooks themselves can be very unreliable as evidence of how people actually eat or ate in the past and that is important to remember. To create a full picture, you need more than books of recipes, which I suppose is one of the reasons there’s such a wide range of ‘stuff’ in the collection.”

“Years ago, I started picking up photographs of people eating, from any era, any situation, as long as there was food and people. It’s quite a large collection now and pre-pandemic the exhibition based on the collection had toured to all sorts of venues. When you see the photographs gathered together I think they tell a very interesting story.”

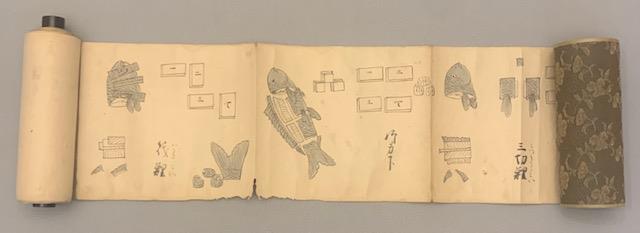

So which period in time would Chris most like to travel to for a foodie experience? “There are eras and places I’d love to travel to, but to choose one is virtually impossible,” he muses. “What I love about a collection is that there is an element of time travel when you engage with it – that’s part of the thrill. So perhaps the parts of the collection I return to most suggest where I would choose. In that case I find that Europe between the wars, Renaissance Italy and 18/19th century Japan are all high on the list.”

The past few years have been unprecedented for our generations but of course pandemics and their impact on life have punctuated history. For Chris, Covid-19 has been interesting in terms of how many people turned to cooking during lockdown. “I don’t think it was simply amusement – I think it became something to hang onto and a comfort,” he explains. “Social changes and challenges and economic pressures were also illustrated through food related issues like the school meals campaign and the threat of food scarcity. And there’s no doubt it has had an impact on food and hospitality sectors.

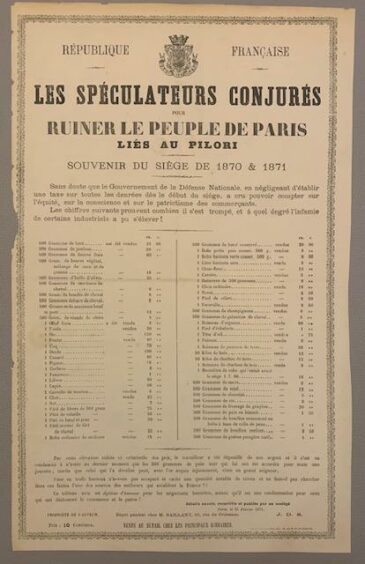

“Plagues, famine and wars have always affected on what we eat. Early cookbooks often mixed recipes with tips for health and diet – they were inseparable. And so you will regularly find recipes for salads alongside cures for plague in the 16th and 17th century books. And charitable campaigns in the past have often used food as a focus as the broadside that was sold to benefit those who were suffering after the Siege of Paris in 1870/71 shows.”

Plans are afoot for the museum to move to its own premises in the near future but in the meantime Chris explains that; “Most visitors experience the museum through a touring exhibition or talk, and these are for everyone and anyone.

“It most powerful when people with a general interest engage with it and find themselves reflecting on their own stories and relationships with food. It’s a very personal thing and I hope by sharing it encourages reflection. I’ve found that the exhibitions create a lot of noise – people chat and reminisce, there’s often quite a lot of laughter and occasionally people are very moved when they happen upon something that connects them to a memory of their own. That can be very rewarding.

“I think I’ll always be collecting and can’t wait to see where the collection takes me in the future. The pandemic meant that my plans for a permanent, public space were put on hold – I hope I’m able to move on with that soon.”

The Food Museum collection is currently kept in a private house that was a former bakery, confectioner’s and butcher’s shop in Auchtermuchty, Fife.

Chris is hopeful that the planned small public gallery and reading room, housed in the former shop, will open in 2022.