Outside the courthouse, there was pandemonium.

The street was awash with people. Clamouring crowds cheered and sang, while politicians in the midst of an election bellowed for justice.

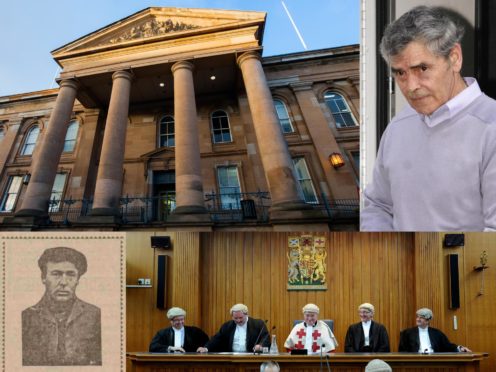

But inside the building, behind those imposing Doric columns, there was only a reverential hush as one man was called to answer the gravest of charges.

That morning – May 3, 1908 – Charles White stood in the dock, accused of an horrific murder that had gripped the City of Discovery for weeks.

It was day one of an epic trial at the high court of Dundee, and another bloody chapter in the institution’s long and violent history.

For court officers, it was just another Monday morning.

150 years of ‘remarkable trials’

There have been countless dramatic testimonies and emotive judgements since the High Court of Dundee began in the 1860s, right up until sittings were ended eight years ago.

The final hearing was marked with a ceremony in October 2013 at which Lord Kinclaven thanked the community for providing jurors, without which “we could not provide our service of criminal justice”.

Presenting him with a photograph of the building from 1950, Sheriff Richard Davidson remarked the courtroom had seen “a number of remarkable trials”.

Following this week’s announcement the high court is to return to the city in an effort to clear a Covid backlog, we look back at some of those cases, from the horrific crimes of serial killer Peter Tobin, to the 13-hour trial of Londoner William Bury, who was described as a “possible candidate” for Jack The Ripper.

The Ann Street Murder of 1908

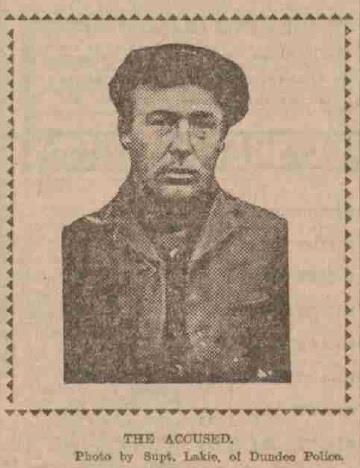

Viewers from the public gallery craned their necks to get a glimpse of the notorious Charles White as he emerged from a hatch, into the dock of the court.

Dressed in a dark blue overcoat and with a twitching upper lip, White denied murdering drinking buddy Patrick Cooney by attacking him in his home at 68 Ann Street with a bottle, a pair of tongs and a poker.

A reporter for the Evening Telegraph and Post noted he was “much stouter” and had grown a moustache since his last court appearance

He added: “His eyes wandered round the court now and then, and it was easy to imagine that at another time, and on a happier occasion, those eyes could twinkle with fun as he sang songs of his native Ireland.”

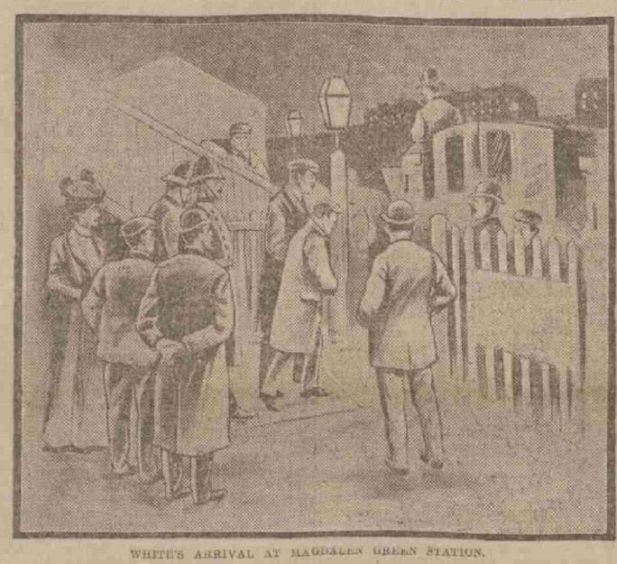

White, a barber from Derry/Londonderry, had been on the run for nine weeks after the killing and was apprehended in Norwich only after a casual run-in with an old friend.

When he was cautioned by police for the murder of Mr Cooney, he replied: “Yes, that’s right.”

The day of the trial had been a busy morning for Dundee.

While the crowds pressed up against the gates of the sheriff court building waiting for the trial to begin, a young Winston Churchill was appealing for votes at an open air rally at the city’s Brown Constable Street.

It was standing room only when key witness John Cooney told how he found his father’s body lying in a pool of blood, underneath his bed. He ran to a neighbour, shouting: “Something erroneous has happened.”

White was identified at the scene by a young boy, who told the trial he had been asked to run “a message” for him.

After a two-day trial, White was found guilty of a reduced charge of culpable homicide and jailed for 14 years.

DNA evidence snared serial killer

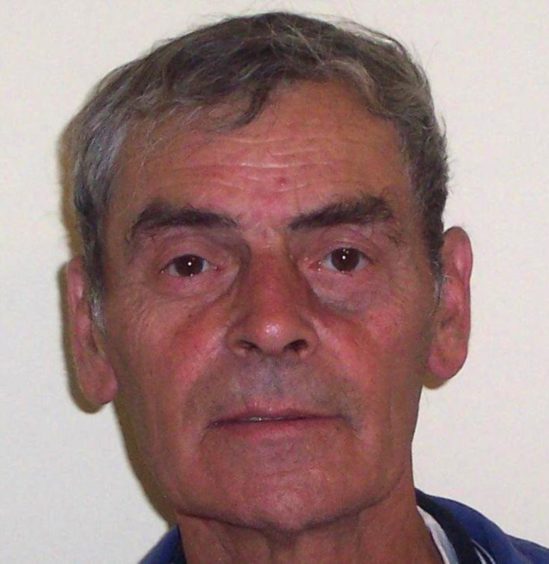

The most high profile case ever heard at Dundee High Court was the trial of serial killer Peter Tobin in winter 2008.

The British media descended on the sheriff court building for the four-week hearing, which finally ended the 17-year-old mystery of what happened to Falkirk schoolgirl Vicky Hamilton.

The teenager vanished in Bathgate in February 1991, while heading home from a weekend visiting her big sister in Livingston – her first bus ride on her own.

Her remains were found, wrapped in plastic and concealed by a carefully poured concrete cap, in a 6ft deep pit in the back garden of Tobin’s former home in Margate, Kent, in 2007.

It was not until the third week of the trial that jurors heard of a direct link between Vicky and Tobin, when a fingerprint analysis of one of the bin bags used to wrap her body produced four distinct prints – all of them a match for Tobin.

The next three cornerstones of the crown case followed rapidly.

A knife with a piece of the schoolgirl’s skin was found in the loft of the house in Bathgate, where Tobin stayed at the time, and there was DNA evidence from her body that produced partial matches with her killer.

The jury took less than two-and-a-half hours to find him guilty, despite defence counsel Donald Findlay QC’s insistence that there was “not a single scrap of evidence” that Tobin had met her when she was alive.

Tobin, who has been linked to a string of unsolved murders and recently reportedly told a fellow prisoner there was a body buried in Scotland that police had not found, was jailed for a minimum of 30 years.

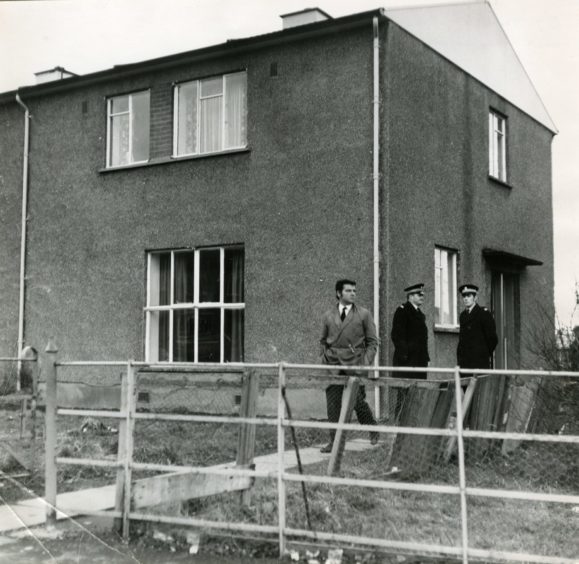

Electricians found mummified remains

One of the grisliest cases ever brought before the high court involved the sad death of self-employed salesman Harry Falconer, whose mummified remains were found underneath a council house in Macalpine Road.

The grim discovery was made by two electricians who were rewiring the three-bedroom property in January 1974.

Mr Falconer’s body, dressed in a shirt, belt, trousers and socks, was lying about seven feet beneath the kitchen floor.

Despite a high profile trial, his case remains open.

The 38-year-old father-of-four was was found directly under a trap door, which had been covered with linoleum tiles, a carpet and furniture.

Mr Falconer was known to drink and take drugs and was last seen between Christmas and Hogmanay in 1972.

Just two days after the discovery of Mr Falconer’s corpse, his wife Isabella was charged with murdering her husband by imprisoning him below the kitchen floor.

The 37-year-old was accused of dragging him to, and dropping him through, the hatchway into a compartment of the foundations of the house while he was unconscious under the influence of drink and drugs.

Mrs Falconer denied the charges during a trial at Dundee High Court in May 1974 and the case was sensationally dropped following the evidence of police surgeon Donald Rushton.

It was the evidence of Dr Rushton that Mr Falconer had survived and probably moved after he had dropped down the hatch.

Dr Rushton, under cross-examination, agreed one of his considerations had been the possibility of a suicide attempt by the deceased.

You can only murder a living person, not a dead one.”

— Lord Stott

Depute fiscal Donald Macaulay said the case against Mrs Falconer could not be corroborated with the evidence available to prove she was guilty.

Lord Stott described the case as “a strange and mysterious matter”.

He said: “In a situation such as this there could be no means of knowing for any of us whether the man was alive or dead when he came into the hatch, and you can only murder a living person, not a dead one.”

Was Jack the Ripper executed in Dundee?

The trial of William Bury in March 1889 was historically significant for two reasons.

Firstly, Bury had the dubious honour of becoming the last man to be hanged in Dundee. And secondly, he may – or may not – have been the infamous serial killer Jack The Ripper.

Bury went on trial for the murder of his wife Ellen, who he claimed had hung herself after a night of heavy drinking.

Investigators went to the couple’s Union Street home and discovered Ellen’s mutilated remains crammed inside a wooden box.

Chalk graffiti on the back door of the flat stated: “Jack Ripper is at the back of this door” and on the stairwell: “Jack Ripper is in this seller”.

It is thought to have been written by a young boy who was never identified.

The High Court trial last 13 hours, with a break for supper.

It emerged Bury had been no stranger to the court and had been spotted listening intently to trials and other proceedings in the weeks leading up to his wife’s death.

By 10.40pm, the jury returned a unanimous verdict of guilty. The mandatory sentence was death by hanging.

Execution was ‘cold-blooded murder’

The day after his execution on April 24, the Courier printed an editorial on capital punishment.

“There are still to be found persons who profess that when one murder has taken place, a second should follow,” it read.

“Yesterday’s proceedings amounted to nothing less than cold-blooded murder.”

Claims Bury was Jack the Ripper began appearing in the press around the time of his arrest.

He had lived in Bow, near Whitechapel, at the time of the notorious killing spree, and the murder of his wife had similarities to the murders of the Ripper’s victims.

Mock trial

Interestingly, William Bury was acquitted at a recreation of his trial by law students from Dundee and Aberdeen universities.

The 2018 mock hearing used modern forensic science techniques, rather than solely medical evidence as was the case in 1889.