He is an Iraq War hero who was decorated after carrying a fatally wounded colleague on his shoulders while being shot at by 50 insurgents.

But more than 15 years after the attack in Basra, the RAF veteran found himself homeless and close to death after being medically discharged from the services and struggling to cope with his mental health.

Now, thanks to the support he’s received during a three-month stay at the Scottish Veterans Residences at Rosendael in Broughty Ferry, he has turned his life around by securing a new job and home on civvy street.

Brought back from the brink

Telling his story to The Courier on condition that we don’t use his name, the former RAF gunner, now in his 40s, explained how, at his lowest point, he was “found in a cemetery”.

“They had to give me CPR to bring me back to life – I woke up in a f***ing nut house!” he said.

Born into an Army family which travelled the world, he never knew civilian life growing up.

It therefore felt natural that he too should join the military.

Joining the RAF in 1997, his 24 years’ service included six tours of Iraq, five tours of Afghanistan, three tours of Nigeria, two tours of Estonia, a tour of the Falklands and two years in Northern Ireland.

A keen boxer, rugby player and football fan, he served at RAF Lossiemouth and worked with 58 Squadron at RAF Leuchars.

He spent much of his working life “helping everybody else”.

Impact of medical discharge from RAF

However, his life came crashing down in 2020 when he was medically discharged after being diagnosed with complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) – or “operational burnout” as the authorities called it – and severe osteoporosis of the hip.

He was also involved in an incident whereby his femur snapped in half.

Used to the “black and white” of military life, he struggled to cope in the less regimented wider world.

A believer in “discipline and consequences” after years of training to be “in the sh*t”, he struggled with the “ambiguity” of modern civilian life which, in turn, took its toll on his relationship with his now ex-partner and children.

His life hit rock bottom and he didn’t know what to do or where to turn.

Then, someone put him in touch with Rosendael, and everything changed.

How did Rosendael offer help?

Walking up the drive towards the former mansion house, he was in tears.

It reminded him of the barracks that offered communal living in the military – his “safe place” which offered stability and identity.

Rosendael gave him opportunities that got him involved with the On Course Foundation and the Caddie School for Soldiers at St Andrews.

They’ve given him reason to “carry on” and for that he’s grateful.

But he knows things could have turned out very different.

“I’m lucky I’ve always managed to screw the nut at the last minute and not put myself ‘inside’,” he said.

“Without this place I couldn’t go on the course.

“Without the course I couldn’t have got the job.

“Without the job I couldn’t get the house. It’s just a cycle.

“If anyone was to ask me who’s a veteran on their ar*e, I’d say get in touch with Scottish Veterans Residences straight away.

“If you need help these guys will help you! It’s amazing what they do and there’s nothing like it in England.”

History of the SVR military charity

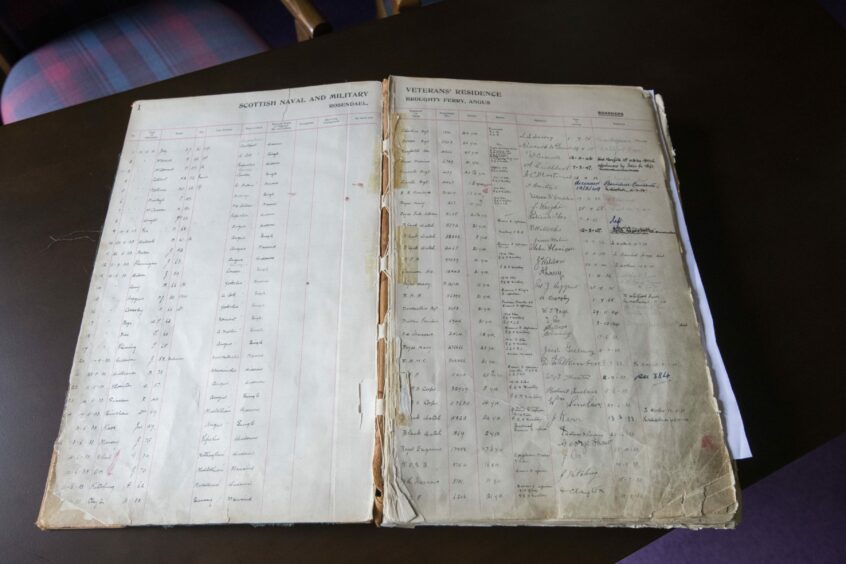

Scottish Veterans Residences (SVR) are Scotland’s oldest military charity, founded in 1910.

And one of their three sites, Rosendael in Broughty Ferry, is this year celebrating its 90th anniversary. The others sites are in Edinburgh and Glasgow.

In 1932 SVR was gifted the Rosendael mansion house by the Proctor Kyd family who had lost their son, Frank Proctor at the battle of the Somme in 1916.

The first name written in the register is S J Jolly, of Southport.

More than 2,200 veterans have lived there since.

What role does the charity play?

Today, it offers accommodation for 44 veterans, currently aged 21 to 90.

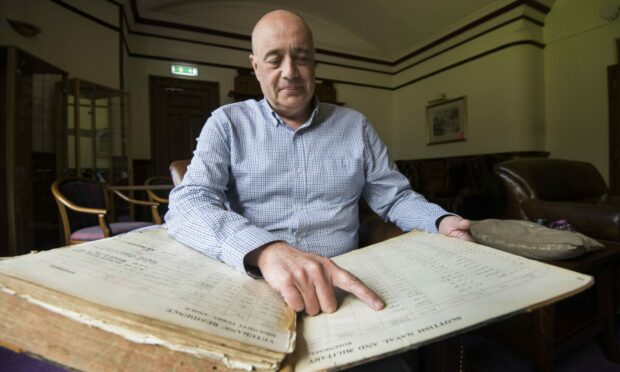

Rosendael manager Graeme Watson describes the residences as a “touch stone” that was very much ahead of its time.

As a civilian charity for ex-service personnel, the starting point is to give veterans space and choices to get back on their feet and help them re-engage with the civilian world.

In 2018, it received a glowing Care Inspectorate report in the wake of concerns raised by former residents and staff.

Individual circumstances are respected, however, and for some, Rosendael becomes their permanent home.

They are “absolutely delighted” with the progress made by this particular veteran.

But Graeme emphasises that it was up to the veteran himself to grab those opportunities and pursue independent living.

“It’s the old story – it’s amazing how lucky you get when you work really hard!” added Graeme.

“What we need to give people when they first arrive is that ability to decompress.

“We don’t meet the real person when they come up the driveway.

“We meet the real person down the line, whether that’s after two, three, four weeks or 18 months.”

‘The Troubles’ in Northern Ireland

“Senseless stupidity” is how a third Rosendael veteran spoken to by The Courier describes his experiences of ‘The Troubles’ in Northern Ireland.

A Protestant by birth, and growing up in a street where his best friend at school was Catholic, the Portadown-born and raised 62-year-old served with the Royal Irish Rangers between the ages of 21 and 29.

Experiences he’s reluctant to talk about include the murder of his Catholic best friend by the IRA, the murder of soldiers in his own regiment and the murder of around 200 people he grew up with in his home town.

There were towns in Northern Ireland he “couldn’t visit” and it was a daily routine for him and wider family members to check for potential car bombs.

When his regiment disbanded, and after years at the sharp-end, he struggled to find support for his mental health issues.

Starting a new life

Encouraged by his sister to get out of Northern Ireland, a week-long holiday to Edinburgh turned into a 14-year stay – including a year spent at the Scottish Veterans’ Residences oldest premises at Whitefoord on the Royal Mile.

He still carries many “bad memories” from his homeland.

Being dispatched to bomb sites amid the carnage of mass casualties was “horrendous” and he “still goes through the nightmares”.

Over the years, he’s suffered more than his fair share of mental trauma, including a break down.

“It impacts on you massively – growing up and seeing how people treat each other,” he said, adding that he’s not been back to Northern Ireland in 16 years.

But since moving to Rosendael almost five years ago, he has managed to find some peace.

Finding peace at Rosendael

Today, he volunteers as the centre’s ‘veterans’ champion’.

He is the conduit between management and residents who want social events whether that be a poker night, dominos or chess night.

A man who likes nothing better than finding peace and solitude through fishing, he’s recently been asked to organise a sea fishing trip for veterans.

But another project he’s immersed himself in is campaigning for the erection of a memorial stone at Barnhill Cemetery where 124 former Rosendael veterans are buried in unmarked graves.

“When I found out about it I thought it was so sad,” he said.

“People who have been here, passed away here and been forgotten about.

“We have a big book of everyone who’s been in the house, right back to 1933.

“There is a Celtic cross from the 1950s or thereabouts at the graves.

“But what we want to do is erect a memorial stone where everyone’s name will be engraved on it.

“It’s painstaking work though.

“You have to match that name with a name we have on list then match that name to a regiment.

“A lot of the regiments don’t even exist anymore after amalgamation.

“It’s time consuming to go through every single name in the ledgers.

“It’s a long term project.

“But we’ll get there in the end!”

Conversation