When mountains are your salvation, how do you cope if they’re out of reach?

That was the very real situation facing Scottish climbing journalist and bipolar disorder sufferer Kieran Cunningham when he found himself locked down in Italy during the early days of Covid-19.

When the Italian government imposed a national lockdown on March 9, 2020, it was one of the toughest Covid-19 quarantines in the world.

The movement of the population was restricted except for necessity, work and health circumstances.

‘Panic mode’

Fife man Kieran Cunningham was living in Lombardy, north Italy, at the time.

The climbing journalist was amongst citizens told they couldn’t leave the house without a letter from police.

Having been diagnosed as bipolar 1 some years earlier, being confined to home sent the now 40-year-old into “panic mode”.

His love for climbing had helped him deal with serious mental health issues.

Yet suddenly, here he was trapped indoors.

“When the lockdown kicked off I went into panic mode,” recalls the former Waid Academy pupil who grew up in Lundin Links.

“How am I going to survive this when I depend on climbing?

“As the weeks progressed and it got worse, I started to notice signs of a manic episode coming.

“I’d managed to get through and walk away from these episodes before.

“But when these things happen, you have no control over what you are doing, and the thing no one ever talks about is suicide.

“I thought I was screwed. I was also running out of medication, which was getting sent over from Scotland.

“My neighbours were dropping like flies. A couple of people in my street died. Then my mum got Covid.

“All these things were making my mental state a little bit more precarious!”

Despair to inspiration

Kieran was in a state of deep despair.

Then one day he wandered out into the garden and had an inspiration.

“I decided to start climbing the walls of my landlady’s house,” he laughs.

“I turned it into a make-shift climbing wall.

“I was still working full time from home at that point but I made sure I got out on the walls several hours each day for the duration of the lockdown.

“This went on for a good three or four months.”

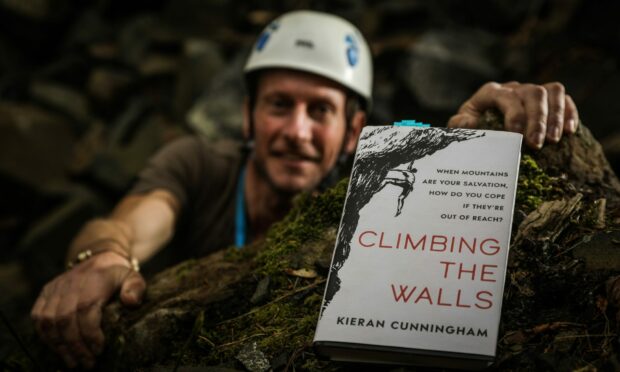

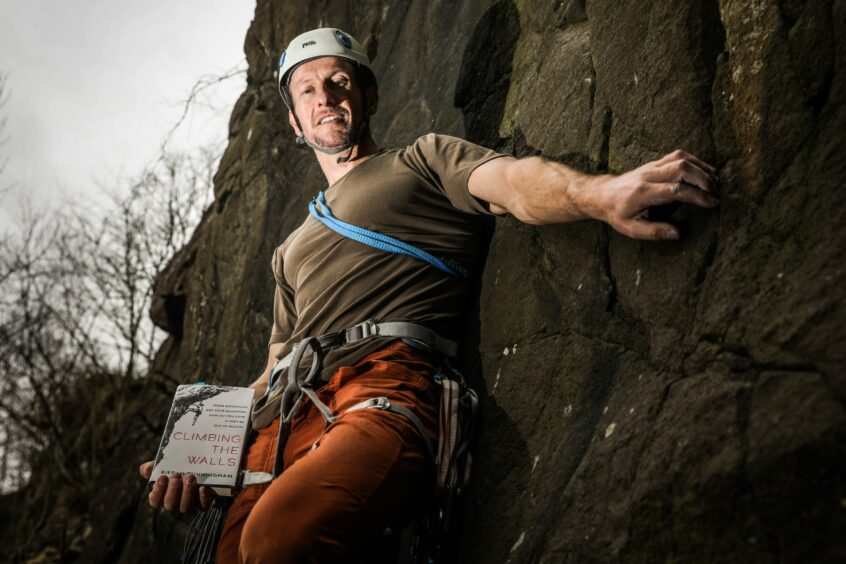

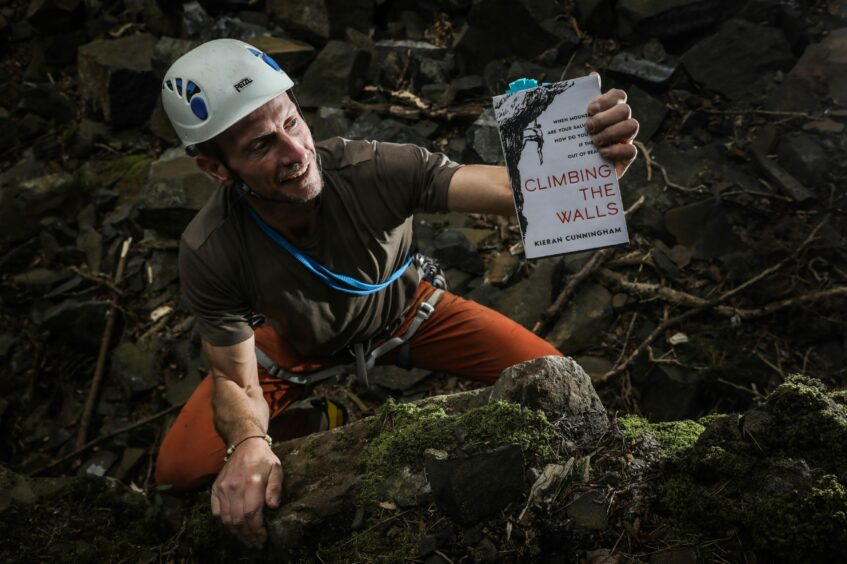

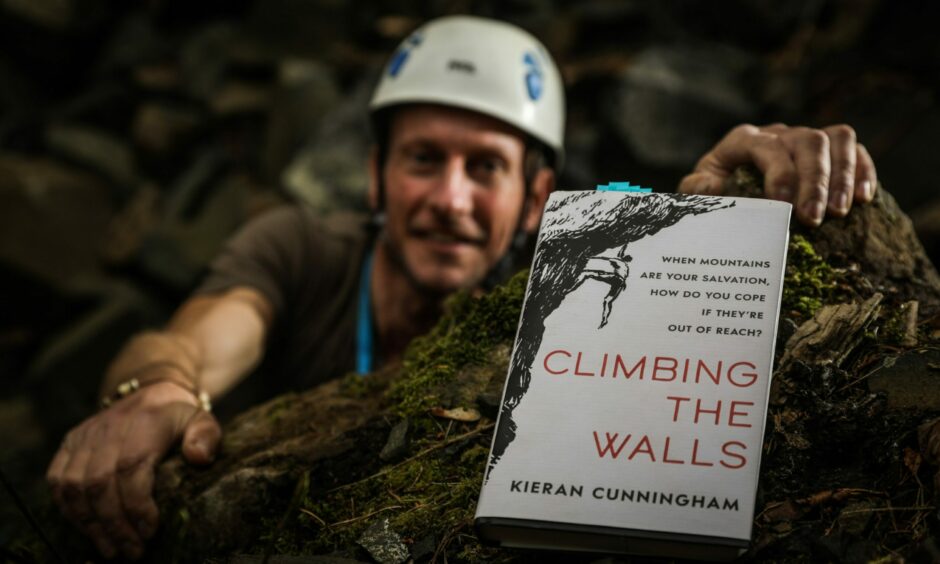

The experience inspired Kieran to write his recently published book Climbing the Walls.

It combines his lifelong love of climbing with his experiences of mental illness and how climbing, and the great outdoors, have helped him.

Lifelong love of climbing

A former pupil of Lundin Mill Primary School, the former Waid pupil studied American Studies at Edinburgh University.

He then moved to Portugal because his then girlfriend was there. He ended up doing a PhD in philosophy.

His love of climbing led him to spend a year in the Himalayas before settling in Italy.

He has his father to thank for getting him into climbing as a youngster.

However, it was during his teenage years that he also started noticing symptoms of what turned out to be bipolar disorder.

“My dad was an incredibly passionate climber and mountaineer when I was young,” he says.

“He dragged me up everything he was doing.

“Then in my teens a few things stopped me climbing.

“My dad’s climbing partner died in an accident in the Highlands.

“I also discovered Tennent’s lager which wasn’t good for my climbing either!

“But it was also then I first started noticing the first symptoms of being bipolar.

“I ended up giving up climbing and didn’t come back to it until I was in my mid-20s.”

Diagnosed with depression

Kieran explains how he was diagnosed with depression when he was 15.

He was “always aware there was always something a wee bit different there” which he never really mentioned to anyone.

His high school girlfriend guessed he might be bipolar. It was something he ignored because he didn’t know what it meant.

But it wasn’t until he was at university that he was properly diagnosed.

He was initially diagnosed as ‘bipolar 2’ before being “upgraded” to ‘bipolar 1’ after being hospitalised for manic episodes.

“It definitely took a toll on my life,” he recalls.

“It was very hard to maintain friendships.

“On the one hand when you are in a depressive episode you don’t want to see anyone – they can last for months at a time.

“Obviously you are not keeping in touch with anyone during that time.

“And then with the manic episodes sometimes your behaviour is so outlandish, no one wants to be around you. That was particularly hard.”

‘Shame and embarrassment’

Kieran said that he didn’t tell anyone about his condition until he was 32.

This was partly because he was in denial but also out of “shame and embarrassment”.

“I really didn’t want anyone to know,” he adds.

“There was no way of explaining what I was going through. People didn’t understand what was happening.”

Greater awareness

Today, however, greater awareness in society means it’s much easier for him to talk about mental health issues than it was 10 or 20 years ago.

“I think awareness is key,” he adds.

“It just speaks volumes. I think back to when I was diagnosed. It was publically not the first but one of the first times I’d heard the expression bipolar.

“People weren’t so open about things then. Certainly not when I was at school over 20 years ago.

“Today I feel a lot more comfortable about sharing it.

“I find the people I do share it with are much more understanding and accepting of it.”

Kieran really struggled with his mental health between his late teens and late 20s.

It was serious at times. He had a couple of overdoses on medication and quite often thought about suicide.

He’d given up climbing as he dealt with his health issues.

However, one day in Italy, he “fell back into it out of desperation” and quickly realised how it helped his state of mind.

Not only was he immediately having less episodes, he was feeling more stable.

Anytime he felt things weren’t going well, he could mitigate the problem at least by spending a day climbing – its own form of medication.

The Great Outdoors

It’s well documented that spending time in the great outdoors is good for mental health.

But climbing in particular has been good for Kieran.

“I’ve spoken about this to my psychiatrist and she explained about the strong dopamine hit you get doing extreme sports,” he says.

“I’ve always said it’s a form of meditation because you have to be absolutely focussed on what you’re doing or really bad things can happen.

“No matter what’s going on in your life you are absolutely zoned in on what you are doing.”

As a youngster, Kieran used to climb with his dad in the Cairngorms, Isle of Skye, Lake District, and on some of local crags including Limekilns, Kirriemuir and Dunkeld.

His dad had a bad accident in his 30s. He shattered his arm and had to get massive screws inserted in his elbow. That reduced his performance a bit. But he still climbs now at 70.

Now based back in Lundin Links, Kieran himself still manages to climb about four times a week – sometimes more, depending on the weather.

He’s built an artificial climbing wall in the attic. In winter, he goes indoors and goes ice climbing up north too.

What’s the book about?

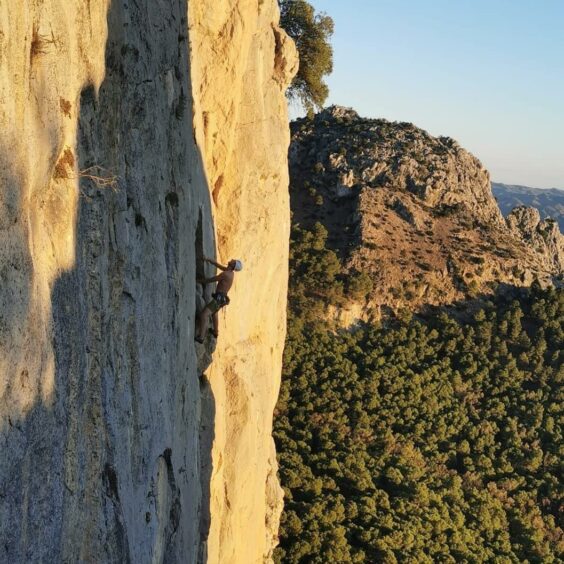

The book covers his many climbing experiences around the world.

He’s climbed mainly in the Alps. But he has also climbed in the Rockies, Himalayas and in England too.

Asked about any stand-out mountaineering experiences, he refers to Kang Yatze in India. That was a 6,300 metre peak which, in terms of mountaineering, he describes as “the best”.

In terms of climbing, he has great memories in Italy at Val di Mello and a spectacular climb at Luna Nascent.

There’s no getting away from the fact it’s a dangerous sport.

Kieran talks about an incident three or four years when he broke his coccyx when doing a solo climb in winter.

“Basically I had to crawl off mountain,” he says. “That was a pretty epic experience!”

Then last year, he and his partner were climbing in the Cairngorms when there was a massive rockfall.

It missed him but the fall very merely took her out at the bottom of the rope.

Then in November, while climbing with a friend in Spain, his friend fell and broke both legs.

“I was there, I witnessed it. I’ve never seen so much blood in my life,” he says.

But he doesn’t let these experiences put him off.

Risk versus reward

“It’s part of the risk,” he adds. “You look at the risk and reward in everything you do. And the reward justifies the risk.”

Asked if he has any yet unfulfilled expeditions on his bucket list, Kieran says there are “too many places”.

Yosemite is the “big one” for rock climbing.

For mountaineering, he’d love to go to Patagonia in South America.

He laughs that when he moved back to Fife from Italy during the second lock down, he went from being surrounded by 4000 metre Alpine peaks to Fife’s slightly more subdued Largo Law!

However, the outdoor website editor hopes his book will help people realise how valuable nature is for coping with mental health issues – wherever they are in the world.

*Climbing the Walls by Kieran Cunningham is out now. The outdoors activity website he works for is https://www.myopencountry.com/