For families across Scotland it started with a simple telegram and photograph bearing the worst possible news — a loved one had fallen in combat.

To many, they were all that was left to remember the fathers and sons lost and as a result they became treasured items.

Vitally, the official documents bore details of where the soldiers had been lost during the full horror of the First World War.

As the war ended, the families would use the information within the documents to try and contact the War Office so that they could visit the graves once peace had been declared.

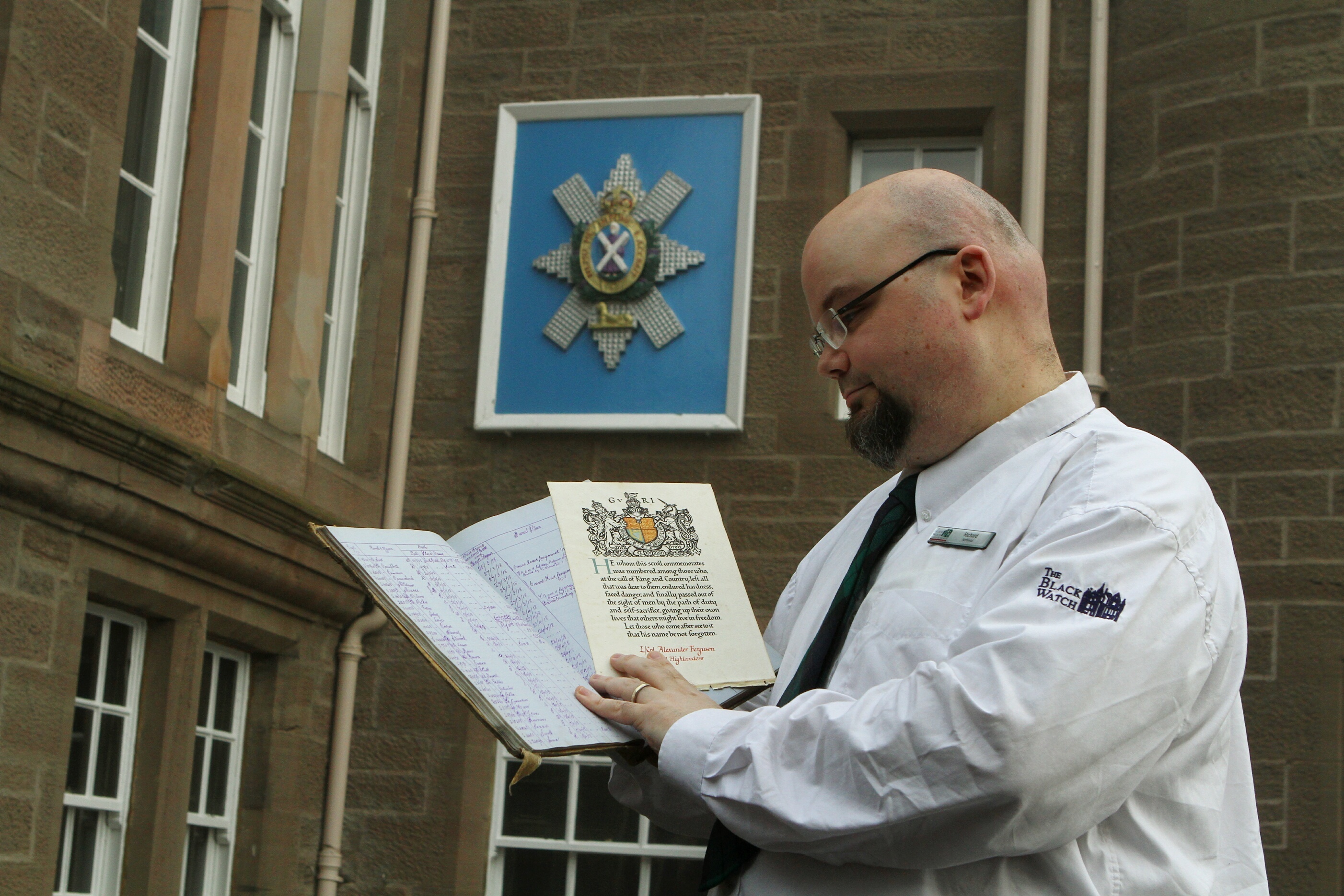

Those important letters were the subject of a poignant talk entitled “My Son Tom” at The Black Watch Castle and Museum, where archivist Richard McKenzie introduced to his audience the idea behind the creation of the Graves Registration Unit.

The talk was inspired by Rudyard Kipling’s poem “My Boy Jack” which was about his son, John Kipling, who was killed on the Western Front in 1915.

With so many dead and dying all over the world, the War Office realised early on in the war that very soon there would be a problem keeping track of the thousands of graves.

As a consequence they were delighted when Fabian Ware, an ambulance officer, came forward with the idea of a registration unit to record where the dead were buried.

By May 1916, the newly created Graves Registration Unit was already managing 50,000 graves.

At the same time as sending members of the team to record the locations of fresh graves, the GRU also found itself the focus for the grieving families left at home.

As a result the remit for the unit expanded and they started to send out official communications to the families informing them where the grave was located and a photograph of it.

Amidst the tumult and horror of war, however, matters were far from simple and many families found that the small solace offered by the telegram was only temporary.

Richard said: “Often desperate and understandably keen to visit the site of their loved ones grave so that they may mourn properly, the families were often left stunned and even outraged when they received information back to tell them that the grave could no longer be found.

“For many this is where it ended, but for some, a lost grave was simply not good enough.

“How could a government be so callous as to simply state that the grave cannot be found, when it was their loved one who died to support those men in office?

“For these people finding their son’s grave became something of a crusade and they spoke with anyone that would listen to try and get their loved one found.

“This, in essence, was the final tragedy of The Great War.”