As the industrial revolution swept Dundee, a wealth of jobs in new industries such as jute were created in the early 1800s.

With these new positions came more people to the city hoping they would be the ones to fill them.

This influx of new residents brought a housing crisis with affordable shelter out the window and with many locals having not a penny to their name they could no longer just rely on the father of the family’s wage to survive.

That is when many turned to a life of crime to feed their loved ones – with women contributing to nearly half of all illegalities by 1885.

From assault, breach of the peace and drunkenness to the act of child stripping, we look at some of the crime which swamped the city’s streets in the 19th century.

Why did crime rates soar?

As Dundee became overcrowded and poverty increased, unfortunately for the population there was no social security or government funding to help them survive.

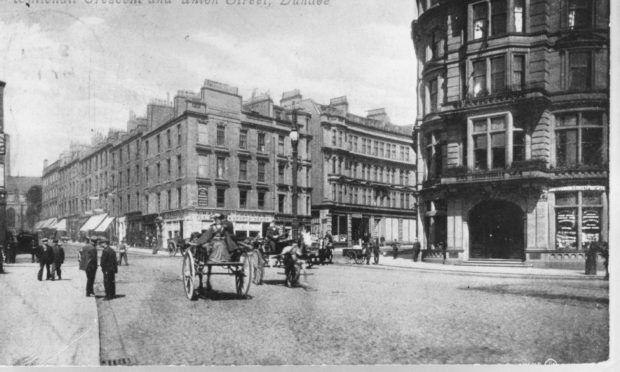

With many people travelling from all over the country to the city in the hopes of securing a job there weren’t enough homes to go round.

Landlords wouldn’t build new homes as it wasn’t profitable for them but one way they could make money was to subdivide tenements and cram as many people and families in the room as possible.

These overcrowded homes were far from sanitary but people were desperate and that was the landlord’s dream.

The types living in these homes were so desperate that for many their only option was to go to the poorhouses or turn to a life of crime.

The latter was more favourable to many.

Between 1820 to 1840, crime reached epidemic proportions in Dundee with high levels of crime continuing throughout the 19th century.

Whilst the majority of these crimes such as house breakings and robberies were carried out by men, women also did their fair share.

Child stripping

During the period there was one crime in particular that preyed on the city’s most vulnerable – children.

It was quick and easy and was particular to the desperate women of the time – the trade of ‘child stripping’.

The offence would see often drunken women target youngsters who were seen to be wearing anything that would be of any value whether that be boots, dresses or sometimes their whole outfits.

One offender who committed an act of child stripping was mill worker Mary Jane Francey. On February 16 1866, Mary Jane’s victim was three-year-old Mary Ann Taylor.

The child was taken to an entry in South Lindsay Street where Mary Jane removed the little girl’s frock which left the youngster practically naked, leaving the toddler freezing on a cold winter’s day.

Francey was found guilty at a later trial with the Baillie jailing her for five days.

In September 1868, the Dundee Courier and Argus, reported on a case of child stripping with Mary Roy being accused of a number of child clothes thefts which she pleaded guilty to.

On Friday August 14 1868, Mary stole a jacket belonging to four-year-old Jane Douglas in Meadowside before continuing her stealing spree the following Monday where she stole the boots of two-year-old Mary Reid in Panmure Street before she headed to North Lindsay Street and again targeted a two-year-old.

This time Peter Leonard was the unfortunate victim with his boots also being stolen.

The following day in Butchart’s Close in the Overgate, Mary Roy stole a dress and pinafore belonging to two-year-old Janet Dow.

The Sheriff in Mary Roy’s case described child stripping as “a species of theft of the worst possible description” and she was jailed for a year.

While the crime was common and many of the stolen clothes ended up in the pawn shop, most incidents were never reported to police.

In 1885, nearly half of all the people arrested in the city were women who were charged with a number of offences including assault, breach of the peace and drunkenness.

Policing in a Victorian Dundee

The Police Commissioners were the first official police force in the city and were appointed in 1824. The force was responsible for lighting, paving and cleansing the town, and a concerted effort to provide gas lighting and pathways began.

Before they were introduced, the Town Council and Magistrates would appoint Town Officers, who would patrol the streets and guard the jails.

The powers granted to Police Commissioners gradually increased as time went on, allowing them to undertake major town refurbishments in the 1870s.

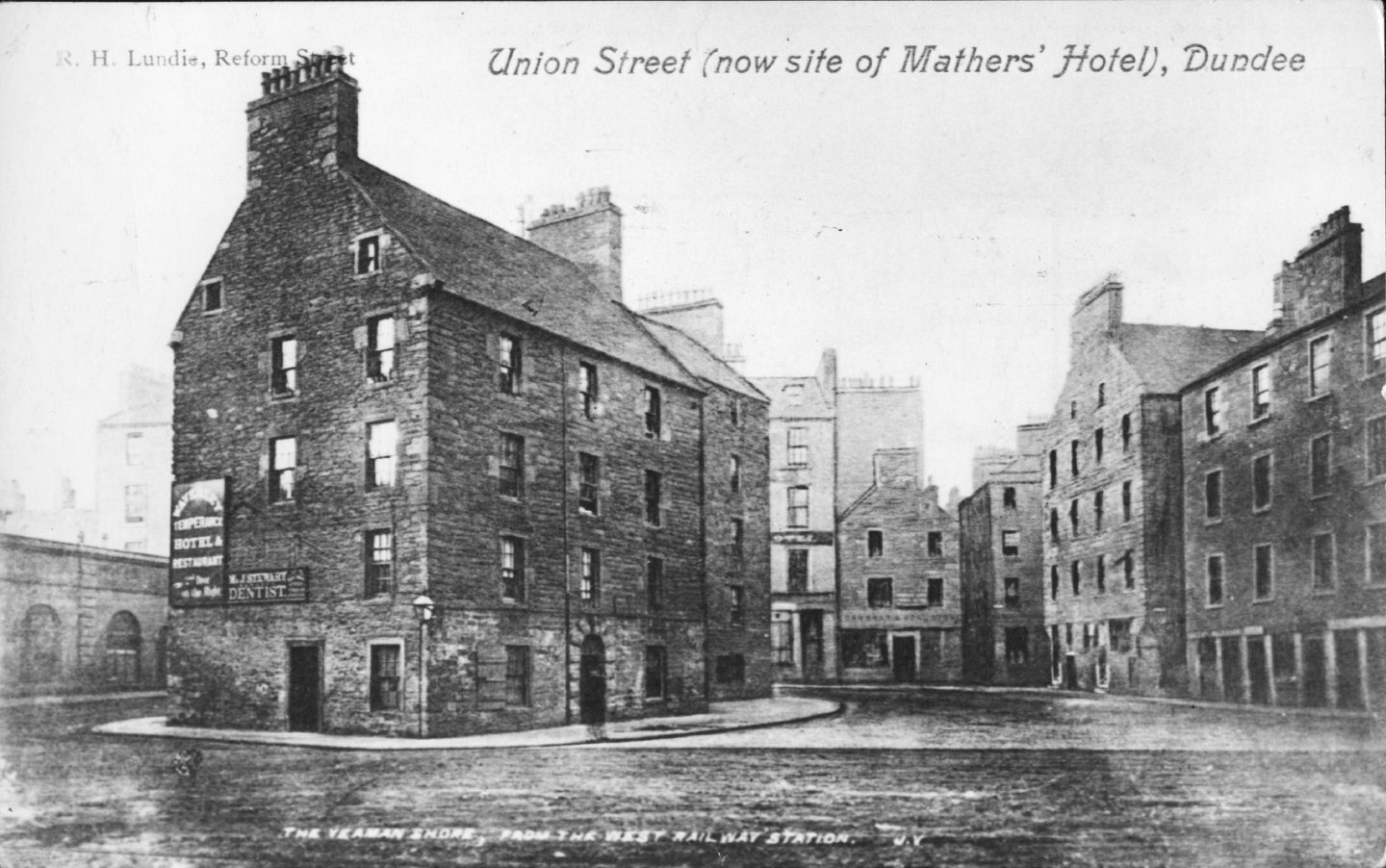

The granting of the ‘Police and Improvement Bill’ cleansing act in 1871 saw the destruction of many of the seedier, overcrowded slum areas of Dundee, which had been seen as the sources of many criminal activities.

The justice system consisted of two courts, the Sherriff Court and the High Court which each travelled on a circuit to different regional locations where cases would be tried.

The most common crimes to be tried in the Sherriff Court were theft and assault, and more difficult cases were referred to the High Court – the supreme criminal court of Scotland.

In addition to being sent to jail or being shipped off to Australia as a punishment, criminals could also be sent to one of a number of other correctional institutions.

You didn’t even have to already be committing crimes to be at risk of being sent away – some Dundonians, mostly children, who were deemed at risk of becoming involved in criminal activities, could be sent to industrial schools.

It was hoped the practical education provided in these schools would prevent them from slipping into a life of crime.

Debauchery causing mayhem

By the middle of the 19th century, Dundee had roughly one pub to every 20 families and it wasn’t just adults who were frequently seen drunk and disorderly around the city as children seemed to enjoy a tipple just as much.

Gambling became a popular form of entertainment with the Howff often crowded with hundreds of people getting involved in illegal betting which earned the Howff the nickname “the paddock”.

In addition to illegal horse-race and dog-race betting, blood sports such as cock fighting and bare fist fighting attracted illegal gambling. These “sports” would often go on without time limits, resulting in some horrifying scenes. Mixed with endless alcohol, fights inevitably broke out, leading to arrests.

The creators of Dark Dundee who share the horrifyingly interesting history of the city with tours explained: “In the late 1870’s, the crime of ‘shebeening’ (selling alcohol without a licence) was a crime committed by more women than men, often landing them with hefty fines or a spell in the gaol.

“Although Dundee had the highest living costs, people living in Dundee were the lowest paid. A large proportion of offenders were sitting in separated cells for not being able to pay their bills, or were being hauled in for drunkenness. Breaches of the peace and assault were also common crimes in these years – the majority of which had been caused by excessive alcohol consumption.”

From the worst to the pettiest of crimes

In 1847 the last public hanging took place in Dundee. The unfortunate soul was a tailor by the name of Thomas Leith who was convicted of poisoning his wife.

He went to his death still protesting his innocence. The execution was unpopular among the local populace and before long capital punishment was carried out behind closed doors.

In the case of Arthur Woods, a gibbet was built especially for his hanging at the new Dundee jail in 1839. A number of death warrants are contained in the Lamb Collection, however, not all of them were carried out – Royal pardons could be applied for and were granted to those lucky enough to have someone intervene for them.

Another trial to have achieved notoriety was the trial of of Mary Elder, or Smith, in 1827, who was more popularly known as “The Wife o’ Denside” and had many ballads and stories written about her. She was accused of murdering her maid-servant, Margaret Warden, by administering arsenic.

A jury returned a verdict of “Not Proven” against her, though popular opinion condemned her as guilty.

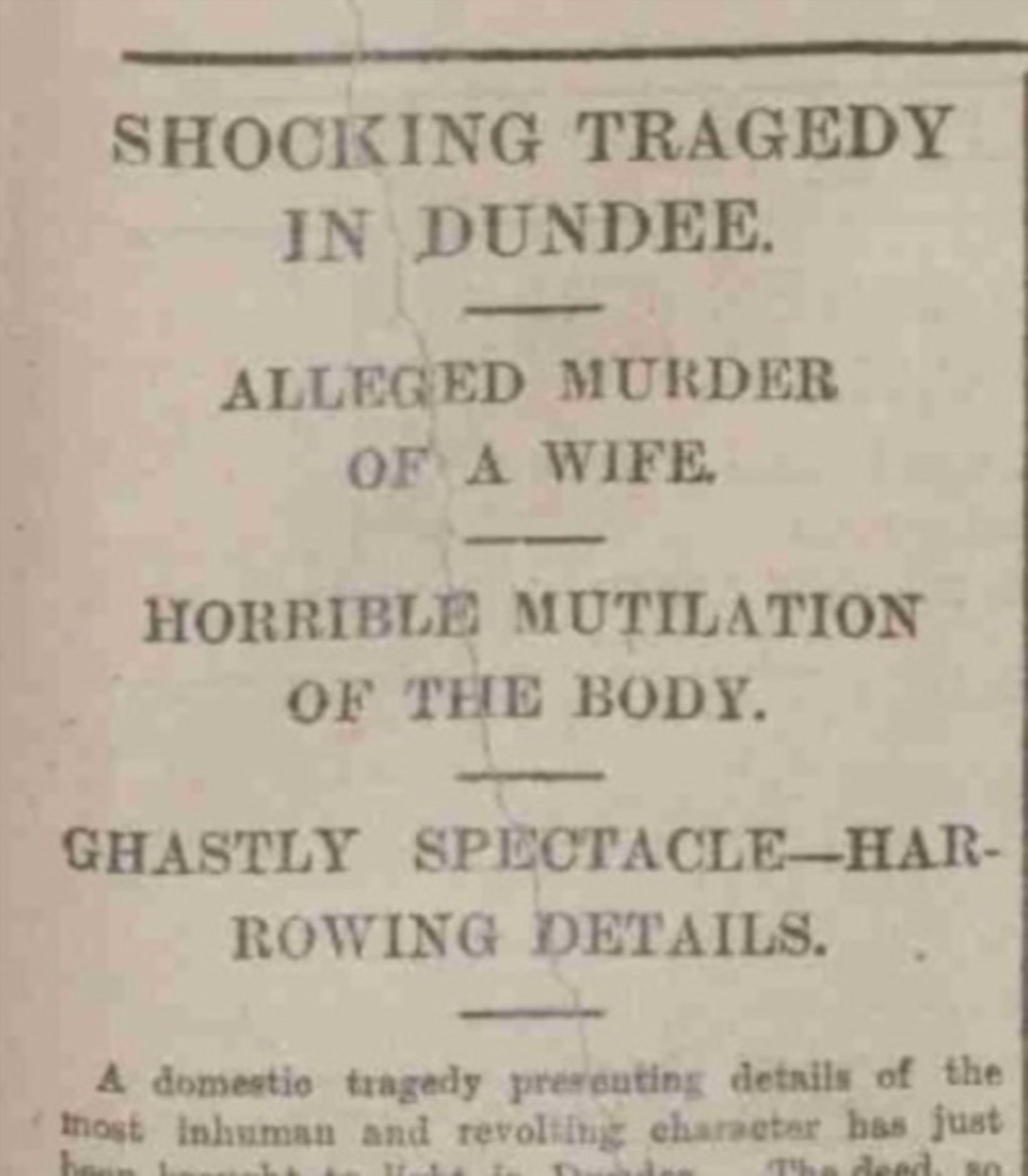

The last execution in the city took place much later in 1889 when William Bury, who some believe may have been involved in the Jack the Ripper killings in London, was hanged the murder of his wife Ellen.

The law was harsh, of that there’s no doubt.

Earlier in the century a person could be shipped off to Australia for stealing a pair of shoes but the last such transport left these shores in 1868.

By the same token, some very minor crimes could be punished by modest fines or perhaps time behind bars — sometimes literally just a few hours to get the message across to a child or a saveable rascal.

Naturally, a lot of the crimes reported in the pages of the local press were of a lesser nature.

Some examples of cases reported in the Evening Telegraph include the following offences which are of a much more petty nature:

- At a Justice of the Peace Court today — Mr Gillespie and Admiral Dougall on the bench — William Clark, shoemaker, Ceres, pleaded guilty to travelling on the North British Railway between Leuchars and Cupar on 16th January without a ticket and with intent to avoid payment. He was fined 10s with 11s costs.

- James Armstrong, Dundee, was charged with stealing a shirt from the door of a clothier’s shop in Hilltown on October 20 last. The charge was aggravated by the prisoner having been twice previously convicted of theft. He pleaded guilty and was sent to prison for three months.

- Catherine Robertson or Manuel, millworker, West Port, was charged with committing a breach of the peace in Perth Road yesterday. She pleaded guilty and asked the Magistrate for a lenient sentence. Catherine said she never tasted drink except on a Saturday after coming from the mill. A fine of 15s or seven days in jail was imposed.