Planners looked upwards to solve Kirkcaldy’s housing crisis in the 1950s.

Records tell us that a Mr Dall from the Kirkcaldy Housing Committee approved its first block of high-rises in 1952.

The eight-storey flats were to be Kirkcaldy’s first venture into cityhood.

He said: “Kirkcaldy is on the way towards becoming a city.

“If we are going to make the best use of land there is no alternative but to build upwards just as cities are doing all over the country.

“We must use our land to the best advantage.”

They saw parties and wakes, Christmas mornings and long, hot school holidays.

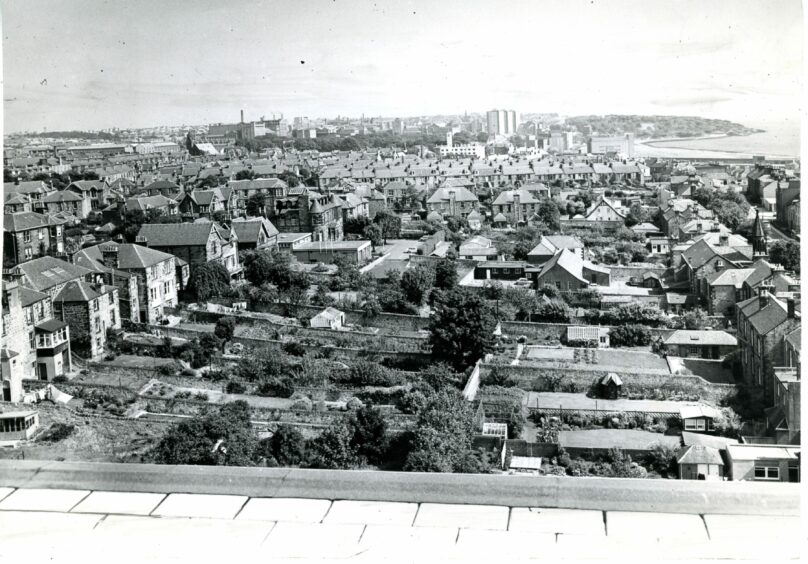

The high-rises remain one of Kirkcaldy’s best-known landmarks some 70 years after being hailed as an escape from the slum housing of post-war Britain.

So what prompted Kirkcaldy’s high-rise boom?

Laying the foundations

Suburbs were expanding in the 1930s and had spread to the edge of the larger Scottish cities.

Private builders were constructing large numbers of suburban homes to have clean running water and electricity.

These new homes were all the rage at a time when ground-breaking ‘luxuries’ such as fridges and radiograms were reliant on power.

The reality was that only a well-off minority could afford the flats.

Soon the council decided that building as many new homes as possible was a higher priority than was concentrating on their quality.

This meant poorer space standards, higher density and less attractive locations.

When the Second World War started, house building stopped altogether.

With no new houses being built, the streets started to become over-crowded and soon developed into slums.

By the 1950s, a housing crisis had broken out in Kirkcaldy.

Around 480 couples were on the waiting list for a home.

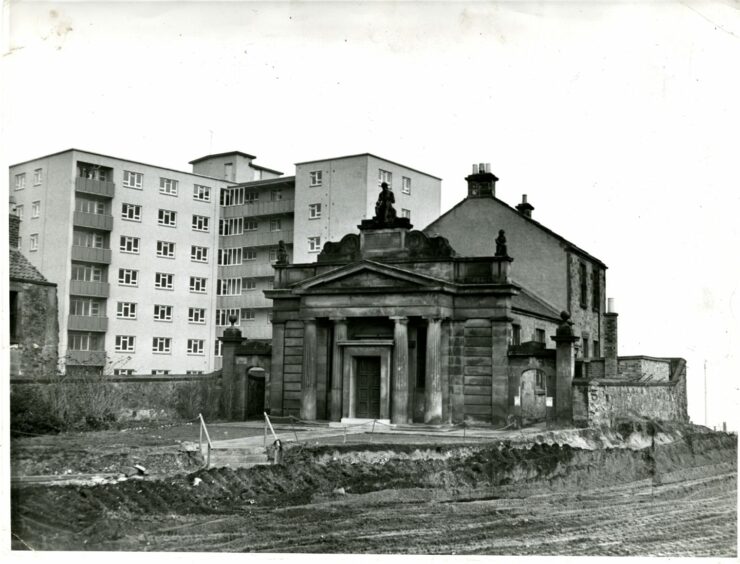

The town’s high rises were posed as the solution at a housing committee meeting in 1952.

Eight-storey towers were to provide accommodation for 40 families.

These could also be adapted to provide accommodation for older people, single people, and two-person households.

The cost per flat was initially predicted to be around £1,800.

Kirkcaldy’s Housing Committee provisionally approved the building of these high rises at eight stories, each containing 40 homes, to be built at Valley Gardens.

However, the plan was shelved and not considered again until 1953.

A report was then brought back before the housing committee which examined the desperate need for high rises in the town.

Councillor Kay, however, was reluctant to proceed with the plans, stating that other cities, such as Glasgow — which had inspired the high-rises idea — were not planning to build any more multi-storey flats.

They had not proved successful from a financial point of view.

There were also several delays with regards to building.

Elsewhere, 94 houses — an average of three per day — had been completed within the burgh, the highest ever attained in its history.

The housing crisis was seemingly being dealt with.

But the new high rises were eventually approved and soon began breaking new ground in all sorts of ways.

In 1954 it was announced that the tower blocks would be the first in Scotland to be electrically heated.

The system would be controlled by a thermostat and used during the off-peak period in the living rooms and corridors of each flat.

Many committee members were horrified at the prospect of 40 separate chimneys on top of each of the high-rises, which prompted their decision to depart from the traditional form of heating.

The removal of chimneys also eliminated the handling of coal and removal of ash.

The Valley Gardens high rises officially opened on Friday June 3 1955.

The all-electric flats had underfloor heating and cost £2,000 each per home.

Soon fully populated, the success of the Valley Gardens high rises led to the development of other high rises in the town.

For thousands of people these would become a happy home for decades.

Three multi-storey blocks were built for Kirkcaldy Borough Council in the 1960s.

Construction of the first two blocks began in 1964 and 1-86 Ravenscraig and 87-172 Ravenscraig consisted of 172 new flats for the borough.

The third and final block, 173-258 Ravenscraig, was built in 1968 and contained another 86 dwellings.

The contractor for both phases was Wimpey, which was also the contractors for Raeburn Heights in Glenrothes.

The Ravenscraig properties took their name from the nearby Ravenscraig Castle.

Built in 1460, the castle was erected on the eastern outskirts of Kirkcaldy for Queen Mary of Gueldres.

It was later turned into a defensive fort.

Kirkcaldy’s multi-storey flats have also inspired artists across the ages.

Scriptwriter and director Adrian Mead, whose credits included the ITV drama Where The Heart Is, selected the Fife town as the location for Over Land And Sea.

Mead wanted to shoot his short film from one of the top-floor Ravenscraig flats to recreate the lighthouse keeper’s living room with a sea view.

That’s not the biggest movie link to Ravenscraig in Kirkcaldy, however.

John Buchan spent part of his childhood in Kirkcaldy and local legend has it several ideas for his best-known works were conceived during his time there.

The well-worn myth goes that Buchan named his most famous book (later to become a movie) after the 39 steps leading down to the beach at the side of Ravenscraig Castle.

There are a lot more than 39 steps on the way down, however!

Although that’s still far fewer steps than you’d take to get up to the top floor of its namesake high rises, which remain part of the town’s fabric to this day.

More like this

Trip back in time: Photographic memories of Kirkcaldy

David Bowie played to a half-empty venue in Kirkcaldy on the day Space Oddity was released