A Fife author is investigating how a pardoned Jacobite rebel managed to outwit the government despite being stripped of his lands and titles after Culloden.

History records that Lieutenant Colonel Sir James Kinloch, of Kinloch Castle, near Meigle, took part in the Jacobite Rising of 1745.

After the Jacobites’ defeat at Culloden in 1746, he was captured in Perthshire with his two brothers then imprisoned in London.

Why were the brothers reprieved?

Sir James and his brothers were sentenced to death despite arguing that under the Act of Union an English court had no jurisdiction over them.

All three were reprieved with James’ two brothers banished never to return whilst James was released on the condition he lived in England.

His baronetcy and lands were forfeited.

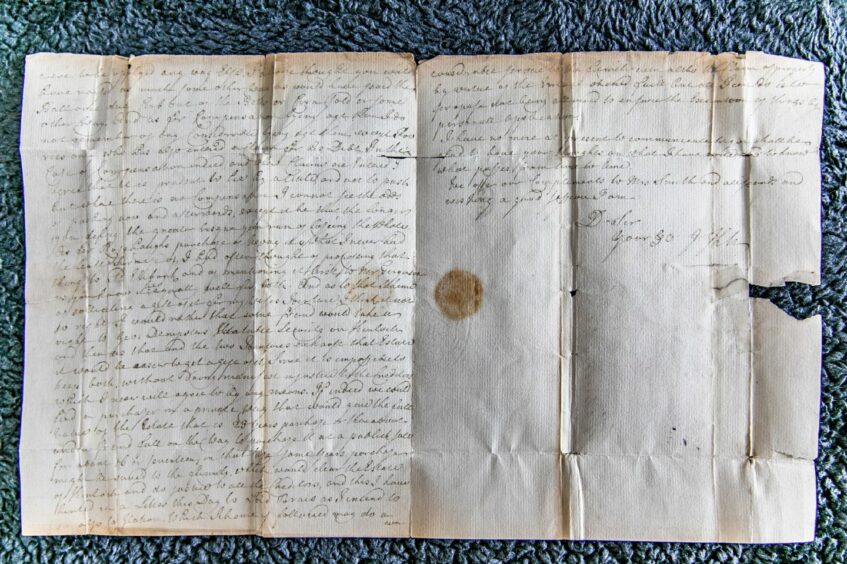

However, Leven-based author and witch historian Leonard Low has acquired a centuries-old manuscript written by Kinloch in 1749, which suggests he had the last laugh.

What does the manuscript reveal?

In the letter written by Kinloch to his son William, he reveals that he kept lands “secret” from the government.

He instructs his son to sell the property to the buyer he has lined up – his cousin George Oliphant Kinloch – and then to give the money to his mother who will get it to him in Barnstaple, Devon.

Speaking to The Courier, Leonard said the letter, which he recently acquired from a collector in Australia, gives a “brilliant insight into a cloak and dagger” episode of history.

“I regularly get offered manuscripts and take a gamble on buying them,” said Leonard.

“This one caught my eye because it was labelled simply ‘Scottish manuscript – might be a Jacobite’.

“It turns out this manuscript dated 1749 is written by Sir James Kinloch.

“He had a castle – Kinloch Castle, near Dundee.

“He was with the Ogilvy regiment and joined to fight with Bonnie Prince Charlie in 1745.

“He was at Culloden in the second line and seemingly his guys were well drilled.

“They marched from the battle and the next day were at Ruthven Barracks to see what would happen next.

“Soon after the battle, Sir James Kinloch got captured in Perthshire with his two brothers.

“He was the Lieutenant Colonel of the Ogilvy regiment which had about 300 odd men.

“He was taken down to London and imprisoned on one of the hulks.

“It was used as a jail, and he was put there, as were many other Jacobites.”

What research has Leonard done?

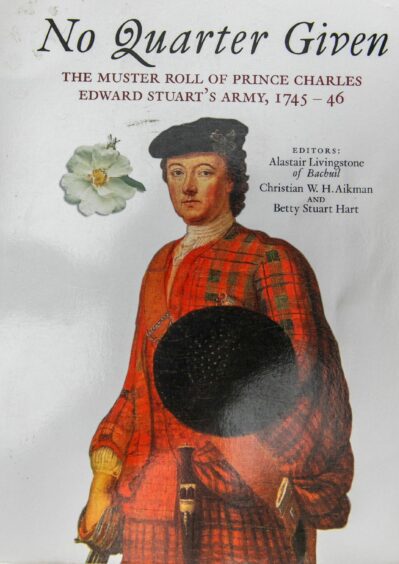

Having researched documents including the muster rolls of Prince Charles Edward Stuart’s Army and other sources, Leonard discovered that Kinloch was sentenced to death for being part of the rebellion.

But somehow – and Leonard has yet to find out why – he was freed.

Presuming that someone must have spoken up for him, he lost his title, his castle and all his lands through a process called “attainment”.

He was told never to set foot in Scotland again.

But the letter, written from Barnstaple, sheds fresh light on this untold chapter.

Leonard added: “This letter just tells his son how he is.

“But he also tells his son that he lied to the government.

“He still owns a fair bit of property and land and houses.

“He’s asking his son in this letter to quickly sell the houses in a secret sale.”

Why was Sir James allowed home?

In 1764, Sir James was allowed to return to Dundee owing to ill health and it was there he eventually died in 1776. He was buried in the Howff.

Although the baronetcy was never restored, the Kinloch lands were.

His son William sold the Kinloch estate to his cousin George Oliphant Kinloch, grandson of James Kinloch, younger brother of the first baronet.

In 1798, George’s son and namesake, George Kinloch a radical politician, designed and built his own Kinloch House near Meigle.

Links to slave trade

George Kinloch – who inherited a Jamaican slave plantation following the death of his father, selling it by 1804 – later said he was “an enemy to slavery in all its forms”.

Known as the ‘radical laird’, he had to flee to France in 1819 after advocating reform.

He later returned to Britain and became the first representative for Dundee in the House of Commons in 1832.

A statue of him was raised in 1872 in Albert Square, Dundee.

*Leonard Low’s updated version of his 2006 book The Weem Witch, was re-published this week.

Conversation