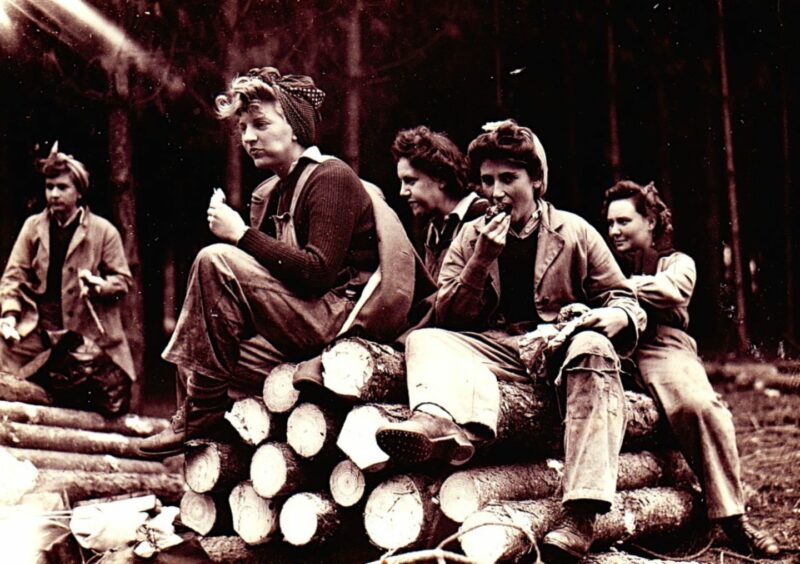

Female forestry workers, known as Lumberjills, did vital work during the Second World War while the men were away fighting. Eighty years on, Michael Alexander speaks to author Joanna Foat about their legacy, including memories from Angus.

At the beginning of the Second World War, Britain was the largest importer of timber in the world.

With only 14,000 people working in the forestry industry and just seven months of timber stockpiled, there was an urgent need for forestry workers.

But with men being sent to the frontlines to fight, a new source of labour had to be found to help supply the war effort with vital wood.

Women’s Timber Corps

Eighty years ago this week, a solution was found with the establishment of the Women’s Timber Corps.

A branch of the Women’s Land Army, they worked tirelessly in Britain’s forests for the duration of the war.

Weeks after the establishment of the corps in England on April 13, 1942, the Scottish Women Timber Corps was established in May with a training camp at Shandford Lodge near Brechin in Angus.

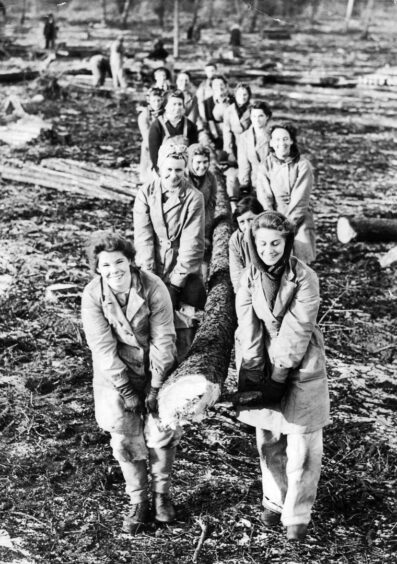

As many as 15,000 to 18,000 young women left home for the first time, aged 17-24, to fell trees with an axe and saw for the war effort.

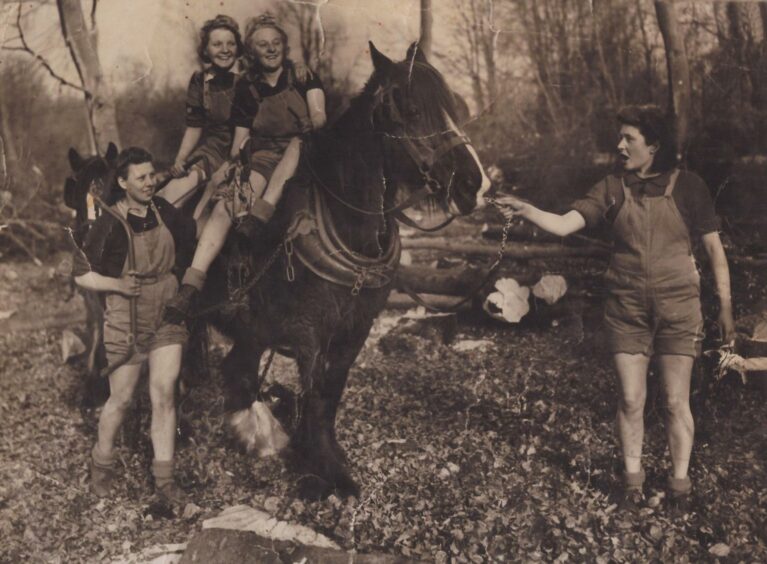

Doing what was thought to be ‘a man’s job’, these pioneering women brought gender stereotypes crashing down.

Yet they faced hostility and prejudice from some men who resented women taking these physical roles.

The government at first refused to employ ‘the fairer sex,’ who they thought would be unable to cope with the tough work.

Instead they tried to employ male British prisoners, male dockyard workers, male students and even school boys.

But thousands of members of the Women’s Land Army wanted to do their bit for the war and the government’s position became untenable.

Author’s research

Author Joanna Foat spent two years interviewing 60 of these remarkable women, who became affectionately known as Lumberjills.

She obtained unique first-hand accounts and evocative photographs of their lives in the forest.

Her book, Lumberjills: Britain’s Forgotten Army came out in 2019 and a Lumberjills novel is due out later this year.

During her research, however, Joanna was shocked to discover how the women were treated at the beginning of the war.

She was also surprised that she’d never heard of the Lumberjills before.

Working in PR and marketing for the Forestry Commission in 2010, it was only when she started researching modern-day successful women in forestry that someone from the HR department of Forestry Commission Scotland, now Forestry and Land Scotland, told her that women working in forestry was “nothing new”.

“I think a lot of people hadn’t heard of the Lumberjills because there was this thing about them being lumped in together with the Land Army,” explains Joanna in an interview with The Courier.

“A lot of them were recruited through the Land Army.

“They were hidden away in the forest which is one thing.

“But I think there was a lot of disbelief that women could have done that job.

“Back in the era there was a lot of prejudice against women – they were a bit of a laughing stock really because people didn’t think they could do it.

“In fact, the Lumberjills not only pioneered a new fashion for women in trousers, wearing jodhpurs, but they also proved that women could carry logs like weight-lifters, work in dangerous sawmills, drive huge timber trucks and calculate timber production figures on which the government depended during wartime.”

Need for timber

When war broke out in September 1939, and having felled much of its timber during the First World War, Britain was importing 96% of its wood.

With the advent of war, home grown timber supplies became vital.

Britain needed to produce millions of tonnes of wood for pit props, railway sleepers, telegraph poles, gun butts, ships, aircraft, as well as packaging boxes for bombs and army supplies.

Thousands of forestry workers were urgently required.

The term ‘Lumberjills’ was coined on April 18 1942, when the Northern Daily Mail reported 25 Lancashire girls, former clerical workers, typists, and hairdressers, left Manchester for a timber training camp in the South-East.

These young women had no idea what was ahead of them when the sign up papers landed on the doormat.

The hairdressers literally swapped scissors and comb for a 7lb axe and a six-foot crosscut saw.

In April 1942, Women’s Timber Corps training camps were set up across England: Culford, near Bury St. Edmonds, in Suffolk, and the Royal Ordinance Factory hostel near Wetherby in Yorkshire.

A month later in May 1942 the Scottish Women Timber Corps established training camps: Shandford Lodge near Brechin in Angus, and Park House, Drumoak in Aberdeenshire.

Hundreds of young women were trained at each camp in four lines of work: felling, haulage, sawmilling and measuring timber.

Many women rivalled the men in their strength and skill.

Memories

One Scottish woman, called Bella Nolan, challenged her foreman to a felling duel when he said he didn’t think much of the women.

Each took one end of the cross cut saw and together they felled 120 trees in a day.

Bonny Macadam, a trainer at Shandford Lodge, near Brechin, recalled meeting new recruits as they stepped off the train at Brechin station.

“There were so many townies – shop assistants, hairdressers – you name them,” she said.

“They had high heels, hats with veils – absolutely incredible!”

The success of the Scottish Women’s Timber Corps made their skills worthy of a spectator sport.

In late 1943, a women’s felling competition was announced in Kirriemuir and 12 pairs of girls took part from camps across Scotland.

Morag Shorthouse recalled: “Jean put my name forward along with that of Mary Curran, so we had to get in a little practice as we had never felled together.

“We were shown the trees we had to fell, the stop watches were set and we started with all eyes on us.

“Unfortunately, we did not get the first prize of a silver cup but we came second.”

Overlooked by government

However, at the end of the war the Women’s Timber Corps received no recognition, grants or gratuities and the director of the Women’s Land Army, Lady Gertrude Denman resigned in protest.

They were not allowed to keep their uniforms or attend Remembrance Day parades, because they were not part of the fighting forces.

The women went back into traditional roles of clerical and shop work, teaching, domestic service or got married.

More than 60 years later, when most of the women were in their 80s, the prime minister, then Gordon Brown, finally presented them with a badge.

But to their disappointment, the badge bore a wheatsheaf, the emblem of the Women’s Land Army, not a pine tree or a pair of crossed axes.

Joanna adds: “One of the reasons I set off on this whole journey was it struck me so strongly these women were really upset that they hadn’t got recognition.

“I could just hear it in their voices.

“I just wanted these women to be recognised for the work they did, because it was so hard and they sacrificed so much.

“They really put themselves out there doing this job that people really didn’t think they could do.

“I thought I just have to help them have a voice and to tell their story so it’s remembered in history.

“It’s really important we can see women as strong and confident to work in any line of work.

“I thought this was a very timely story that’s really important to be to heard.”

Inspired by nature

Today, Joanna works for Surrey Wildlife Trust. Writing about nature is “wonderful”, she says, because it gives her the confidence when writing fiction to include the intricacies of biodiversity and ecology.

She also loves being out in the forests.

“When I was a girl I used to go out the back of my house to ‘out the back’,” she says.

“I used to plant trees. It was quite a suburban area but there was like a little oasis of forest and trees and woodland and bluebells.

“That was like my playground where I used to meet local kids and hang out and climb trees.

“That’s partly where my love of nature and being out in the forest. I’m quite a free spirited person.”

Something else that helps her relate to the stories of the Lumberjills is her own love of chopping wood – something which was encouraged when her dad bought her an axe one Christmas.

With the 80th anniversary upon us, she also hopes that women of all ages can be inspired.

“I hope to inspire women of all ages with the strength, courage and determination of the Lumberjills,” she says.

“Out in the forests away from the restrictions imposed on women by society, they realised they could sit astride a tree, smoke a pipe and fell 10 tonne trees just like the men, if they wanted to.”

*Lumberjills Britain’s Forgotten Army by Joanna Foat is published by the History Press.