Ahead of a talk he is giving in Dundee on November 1, the Pope’s chief stargazer Dr Guy Consolmagno tells Michael Alexander why he believes faith and science enhance each other.

Whether it’s ‘leave/remain’ in the Brexit arena or ‘yes/no’ in the context of the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, it sometimes feels as if we have come to live in a world dominated by binary choices with little room for three-dimensional thought.

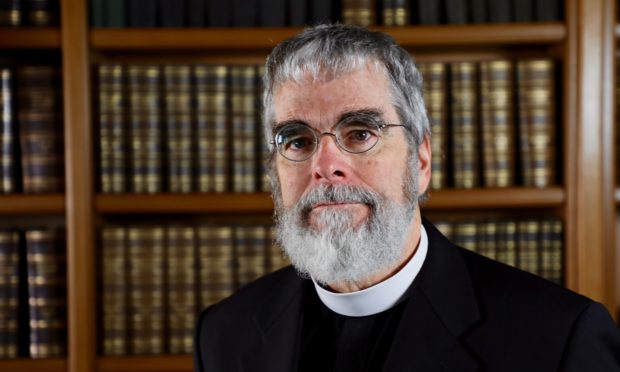

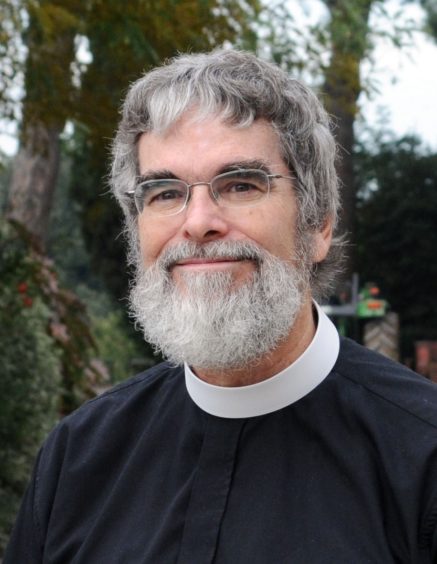

However, as the Pope’s chief stargazer Brother Guy Consolmagno prepares to give a talk in Dundee about the astronomical proportions of the heavens, he sees no reason why the sometimes polar opposite worlds of science and religion should not co-exist.

“The funny thing is I have a really hard time understanding why anybody thinks science and religion are opposites because the two have always co-existed so easily in my life,” said Brother Consolmagno in an interview with The Courier.

“The trouble is most of us stop learning religion when we are 12 and most of us stop learning science when we are 12.

“When they are lived experiences you realise they are constant endless explorations and both have techniques to try and explore reality and complement each other.

“Having more than one point of view is essential for any good story…and allows you to enjoy how each view of reality brings out reality in three dimensions so to speak.”

Known fondly as ‘The Pope’s Astronomer’, Brother Consolmagno, 67, was born in Detroit, Michigan in 1952 and has combined science and religious thought throughout his life.

From starting school in 1957 when Sputnik was launched to his departure from high school in 1969 when man first landed on the moon, he was inspired by the space programme – and science fiction – to become a scientist, going on to study planetary science at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and doing his PhD at the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory.

After teaching at Harvard College Observatory and MIT, he served with the US Peace Corps in Kenya for two years followed by a spell as an assistant professor in Pennsylvania.

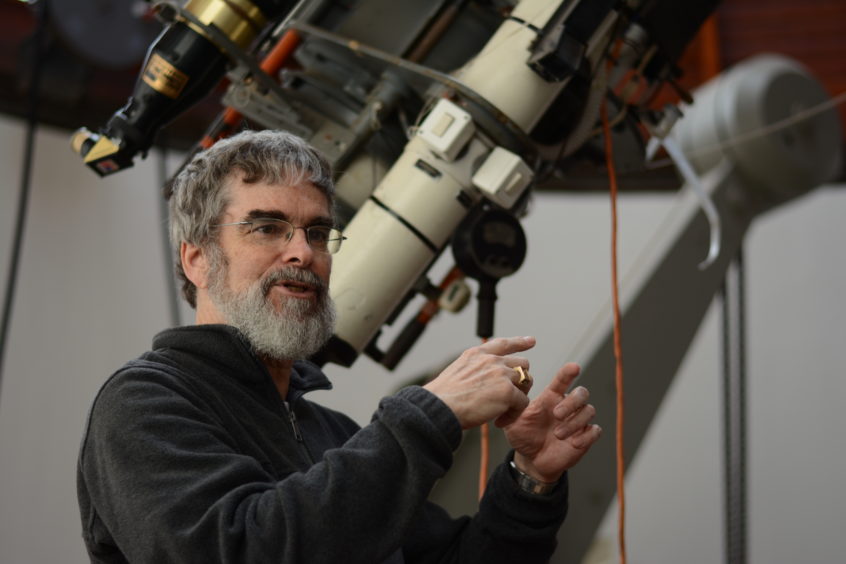

However, it was in 1989 when he entered the Society of Jesus – a religious order of the Catholic Church in Rome – and took his vows as a brother in 1991, that he was assigned as an astronomer to the Vatican Observatory where he also serves as curator of the Vatican Meteorite collection.

He was named by Pope Francis as Director of the Vatican Observatory in September 2015.

On Friday November 1, as part of a seven-date tour of Scotland organised by the interdenominational Scottish church group Grasping the Nettle, he will attend a schools conference at Grove Academy, Broughty Ferry, before giving an illustrated talk at Dundee Science Centre in the evening called The History of Strange Ideas (including God?).

“When you get to be my age and your hair starts to turn grey, you realise that the history of science takes on a new meaning because I lived through some of it,” he laughed.

“It brings you a new appreciation of what science is and it isn’t.

“What better way than to tell stories – in some instances funny stories – of the crazy ideas that people had in the past.

“My goal is to talk about some wonderful ways that people used to think the universe worked and how in fact we now know better. They give you a sense of ‘oh why would anyone think that?’ But how do we know better?

“For example, we’ve all heard the phrase ‘the High Seas’. To find out where that phrase actually comes from, you have to understand how people actually once thought the oceans were higher than the earth, and why they thought that.

“Number one: it helps me appreciate the creativity of the human mind.

“But also it makes me a little more likely to recognise that what seems to be common sense in 2019 may look really silly in 2119. That’s always a humbling thing to remember!”

Based at the Papal Gardens at Castel Gandolfo, 20 miles south of Rome, Brother Consolmagno describes Pope Francis as a “wonderful, very friendly and very sharp guy”.

He said the main reason the Vatican observatory exists is “public relations” and to acknowledge that the church respects and acknowledges science.

“In some ways it’s a missionary of science to church goers,” he said.

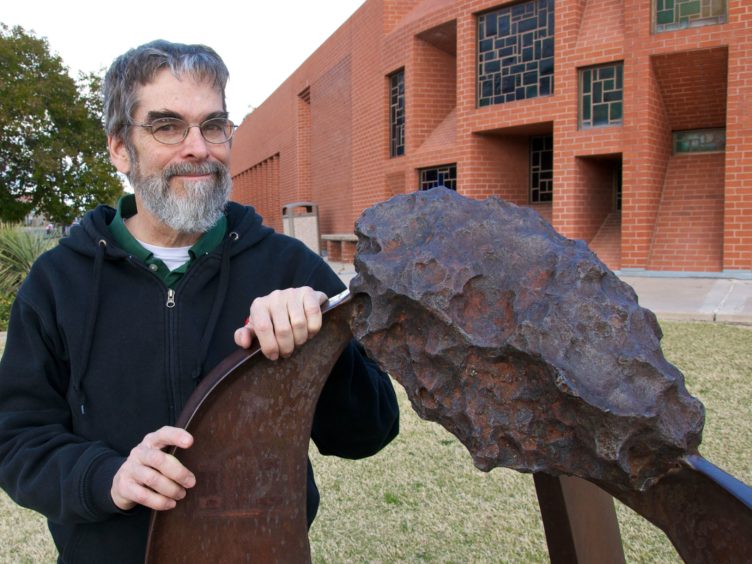

Brother Consolmagno, who had an asteroid named after him by the International Astronomical Union in 2000, specialises in meteoritics – the study of meteorites/rocks that fall from the sky – and collaborates with scientists from all over the world.

He has never lost his child-like love of looking at the stars – the main difference now being that he knows their names and their histories.

But he has also never lost sight of the role religion has to play in trying to make sense of life and the universe.

“Religion is what it’s always been,” he said.

“It’s just to remind people – just as astronomy does – that the universe is bigger than what you had for lunch. The universe is bigger than ‘is my boss mad at me or are my kids going to be in trouble tomorrow’?

“It puts things in a bigger perspective and it makes you ask the questions – who are we? Why are we here? What are we supposed to be doing? It doesn’t necessarily supply the answers.

“But it supplies the boundaries inside of which we can come up with the answers.

“Astronomy does that and religion does it – different sets of boundaries. But that’s great because it helps narrow down where you are likely to find the answers.”

· Discarded Images: The History of Strange Ideas (inclding God?) takes place at Dundee Science Centre on Friday November 1 at 7.30pm. For ticket information go to www.graspingthenettle.org/events/dr_guy_consolmagno_illustrated_talk