When Fife man David Hamilton returned safely from his third humanitarian aid mission to Ukraine in May, he knew he couldn’t have done it without the support of his family.

He describes his children Holly, 14, and Rory, 12 – both pupils at Bell Baxter High School in Cupar – as the “real heroes” for letting him go.

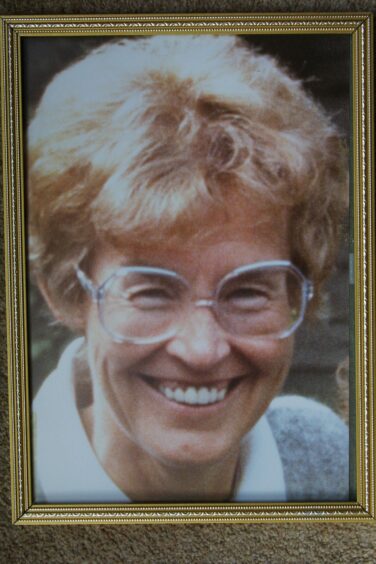

But he’s especially grateful for the support of his wife Julie who, 30 years ago, lost her own mother Christine Witcutt, on an aid mission to Bosnia.

Mother-in-law shot dead in Bosnia

The experienced aid worker was shot dead whilst leaving Sarajevo with an aid convoy in 1993.

“When I set off for Ukraine, I never say to my wife, ‘don’t worry it’ll be fine’, because that’s exactly what her mum said to her 30 years ago,” said David.

“But she knows I have a lot of experience of this now. I’m constantly risk assessing it.

“That’s probably the most exhausting bit.

“Everything you do on these trips you have to have a contingency plan.

“It’s a big ask for her.

“But she knows that I do that and she knows that I look after myself and that I’m not going to take any unnecessary risk.

“The risk has got to be balanced with the good that you are doing.

“Otherwise I wouldn’t be doing it.”

Decades of humanitarian aid experience

David, 51, is no stranger to the dangers of delivering humanitarian aid to conflict zones.

The founder of the charity Remembering Srebrenica Scotland, who sits on the committee of relief agency Edinburgh Direct Aid, drove relief lorries to Sarajevo under heavy gun fire during the four-year siege of the city by Bosnian Serb forces in the mid-1990s.

He first volunteered as an aid convoy driver after becoming disillusioned with life as a 22-year-old travelling salesman in 1994.

However, having just returned from his third aid trip to Ukraine in 14 months, David is in no doubt this was his most “incredible and shocking” experience yet.

What did David experience in Ukraine?

Travelling as far down as Donetsk Oblast, which was recently vacated by occupying Russian forces, the hardship and challenges facing ordinary Ukrainians are “unimaginable”, he said, and the “most extreme” he’s ever seen.

He found it hard to contain the “rage” he felt towards the Russian Army and their “barbaric and criminal practices and wanton destruction”.

But he also took hope from the “wonderful” Ukrainian people.

They range from people who asked only for what they desperately needed, to the young Ukrainian volunteers who give their own time and money to help their fellow citizens.

Inspired to make a difference

David, who lives in Letham, near Cupar, recently retired as chairman of the Scottish Police Federation after almost 27 years police service.

Having travelled to the Poland-Ukraine border to help refugees shortly after the Russian invasion of Ukraine last year, he returned last May to deliver food in Lviv.

One of the first things he did when retiring from the police was make a plan to go back.

Travelling with retired naval commodore David Pond who he met through a policing charity, they flew from Edinburgh to Krakow then on to Przemysl near the Poland-Ukraine border.

Crossing the border by foot – and laughing that they nearly got picked up by the Foreign Legion who thought they were military on their way to fight – they got a minibus-taxi up to Lviv then the overnight sleeper train to Kharkiv in the east.

Having previously bought a vehicle for a Ukrainian charity, the aim was to go out and see what else they could do to help.

They planned to deliver food to agricultural communities in the largely rural Kharkiv Oblast district.

The difficulty, they’d heard, was the Russians had mined a lot of the area so people couldn’t work the fields and therefore couldn’t generate income.

Identifying needs of local population

But when they got there, the charity told them that instead of food – which was being provided by another charity – what a devastated town they’d identified really wanted was building materials.

Working with local builders, they visited a merchant where they loaded up vans with wood, cement, roofing felt and nails.

They then travelled south of Kharkiv to a town called Dovhen’ke, just 25 miles from the frontline.

It was here that David was shocked by the scale of the devastation.

Yet he was struck by the defiance of the Ukrainian people and their determination to rebuild.

Roadside mines and devastation

“The journey down itself was pretty hairy,” he said.

“It was mined on either side of the road.

“You are going through towns and cities like Izyum where a lot of mass graves were found after the Russians had left.

“It was hammered as a city. Really bad.

“But when we got to Dovhen’ke, that was just different scale.

“Every single part of the area was destroyed and devastated.

“There were burnt out tanks, armoured personnel carriers, munitions everywhere, shells lying in the street, rockets sticking out the ground, bullets.

“It’s just incredible. Every single house had been blown up or set on fire or damaged.

“There were Russian ration packs and uniforms just littered everywhere.

“Because when they took that area last June, and used it as a base to do their own operations from, they just wrecked the place.

“They stayed there for about three months before the Ukrainians finally drove them out.

“But it changed hands 18 times between the two different armies. It was absolutely trashed.”

Defiant Ukrainians determined to rebuild

When it came to Dovhen’ke itself, they couldn’t believe anyone could live there.

Yet when they arrived, they found 16 people determined to rebuild their lives.

“Your obvious question is ‘why are you doing this?’ said David.

“They basically say ‘because it’s home’. It’s all they know.

“It’s where their livelihood is. It’s their fields.

“They are trying to rebuild their houses and make them weather tight.

“But at the same time all the ground is mined.

“We just couldn’t stand on the grass, other than where they’d cleared it themselves.

“That was terrifying in itself that people were clearing mines out of fields but scooping them up with a spade and flinging them to the side!”

The wanton and wilful destruction reminded him of Bosnia during the 1990s.

But in Ukraine, the cruelty and “evil” was to a different degree.

“I think there’s a real malevolence in what I saw this time,” he said.

“Because this wasn’t just a case of planting mines to stop or slow down the advance of another army.

“These mines were booby trapped.

“So rather than just placing one mine, there would be one in the ground, one in the tree and one would be hanging off a branch.

“There were three different ways to maim and injure people.

“But this was agricultural land so clearly the mines were aimed at civilians to stop people from eating and to stop them making a living.

“You’ve literally got people ploughing fields around craters with rockets sticking out of the ground.”

At least 750 years to clear mines in Ukraine

Due to the prevalence of mines, David said it was essential to stick very closely to trodden paths.

At current rates, it’s estimated it’ll take over 750 years to clear the mines that are known about.

That’s before any counteroffensive which will add more to the tally as more land is reclaimed.

Yet on his way into the village, he got a massive fright while driving one of the vans.

“There was a massive explosion,” he said.

“I jumped out my skin.

“One of the tyres had blown out.

“I was relieved to find it was just a puncture.

Lucky boy. Think I must be the only person who has punctured a wheel on a Russian rocket. 😬 pic.twitter.com/yV9vhk8nGj

— David Hamilton 🏴🇺🇦 (@DvdHmltn) May 22, 2023

“But then when I went to see what I had punctured it on, it was a Russian rocket that was half in the ground and half out.

“Crazy stuff!

“You are literally driving up through the village and you see a front garden and a rocket sticking out.

“You see folk walking round it.

“Working on the basis it’s been there since last summer and probably isn’t going to go off. But it’s crazy.”

‘Incredible’ attitude of Ukrainian people

David said the attitude of the Ukrainian people has been “incredible”.

Working with a variety of organisations – including a resistance group – he’s been impressed by the Ukrainian efforts to engineer solutions to problems.

Amongst them are the young NGOs: young Ukrainian students who are running charities and people working in the arts who are going down to help villagers.

But there’s only so much they can do themselves.

That’s where they continue needing assistance from charities.

Edinburgh Direct Aid has delivered food, firewood and now building supplies.

Further projects being looked at include getting electronic tablets to children in Kharkiv, who haven’t been able to attend school since the 2022 invasion.

Having spoken to one of the MPs out there, David hopes to put together a programme encouraging people to donate their old tablet computers for Ukrainian children.

How to support Edinburgh Direct Aid

David and his brother Duncan are returning to Ukraine, driving a specialist vehicle where it will be used to support children traumatised by the war in their country.

Thousands of children are ‘internally displaced’ in Ukraine and many are traumatised by what they have experienced.

To support this campaign, go to www.edinburghdirectaid.co.uk/ukrainekids

Conversation