They were the automotive pioneers who almost took the car industry Back to the Future.

At the dawn of the motoring era a century and more ago, firms from Dunfermline, Dundee, Angus and the Mearns ventured into car making.

Marty McFly wouldn’t have looked out of place behind the wheel of the Dalhousie which was a four-cylinder roadster with steeply raked bonnet and cabriolet top.

Anderson-Grice started producing the Dalhousie between 1908 and 1910 at Taymouth Engineering Works in Carnoustie.

Anderson-Grice began life in 1875 at the Arbroath Foundry in Dickfield Street and quickly outgrew its original premises and moved in 1886 to the vacated Taymouth Linen Works at Carnoustie.

Founder George Anderson was an excellent engineer and familiar with the needs of the quarry industry.

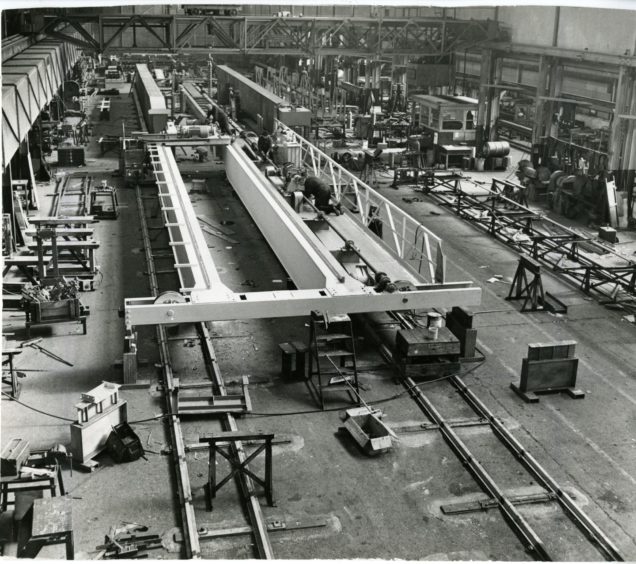

His foundry specialised in cranes, stone cutting and planing machinery.

He was joined by AG Grice around the turn of the century and he probably led the firm into its brief car-making foray.

He designed the Dalhousie and he later joined the car-maker GWK as chief designer.

Anderson-Grice built a small number of cars but the project was abandoned and sold to James Law in Arbroath after they were found to be too expensive for ready sale.

James Law also bought all the Dalhousie spare parts and it is thought he may have built a handful more cars, using the spares stock and adding whatever else was required.

Anderson-Grice continued for many decades, making quarrying machinery and various types of cranes and even made equipment used to help salvage the German fleet from Scapa Flow.

Then there was Douglas Fraser & Sons, from Arbroath, which made a few steam-powered cars in 1911.

The family firm was established in the early 1830s before expanding their business into Argentina after Mr Fraser’s youngest son, Norman, invented a machine for plaiting jute to make candlewick in 1881.

It was the invention that made the Fraser fortune.

The firm was looking for ways to diversify and identified an opportunity for mechanising the production of jute-soled shoes called alpargatas using this technology.

The Fraser family were prominent among the early car owners in Angus.

Simon Fraser from Dunkeld, whose grandfather was Norman Fraser, said there was never any commercial intent associated with the car-making venture.

He said: “The story, as related to me by my father, is that the Fraser family acquired the French 1903 Miese steam car but were not wholly satisfied with it.

“Norman thought he could do better, and set about constructing his own steam cars, both in his own workshop at Ogilvy Place and using the facilities at Douglas Fraser & Sons.

“These cars were for his own use and for the use of his brothers who were Dr Tom at Springfield Terrace, Patrick in Dalhousie Place, John at Monkbarns and Robert at Cairnie Hill.

“I am told that Tom Clark, bicycle salesman and engineer, whose shop was on the corner of the High Street and James Street I recall, was an accomplice of Norman’s in this car building, a friendship which doubtless originated when the Fraser brothers were designing their own bikes.

“I have never heard that there was ever any commercial intent associated with this car building enterprise.

“I understand that, while the cars took a wee while – 20 minutes rings a bell – to get going in the morning, and water had of course to be taken on from time to time, they gave a very comfortable ride and could do 60mph.

“The coachwork was purchased, as may have been the case with some other components such as wheels and steering.

“Hence they appeared not dissimilar to other vintage cars.

“The cars will have been a novel sight in the town prior to the First World War and quite an experience to ride in.

“My father related a tale of a Miss Salmond, who, having been taken for a spin in a steam car down the Lovers’ Loan to St Vigeans, took fright and leapt from the car when travelling at significant speed.

“Sadly, I don’t recall the outcome!

“Another story was of how, as a youngster, he was taken out for a drive by his father and, given a shot at the wheel, he succeeded in rolling the car.

“All was resolved when the local farmer, somewhere near Colliston, was asked to use his tractor to right the car.

“If a part required replacement, it was a simple matter of asking somebody at the works.”

The British Film Institute released a 14-minute clip of the Fraser family at their mansion in the town’s Cairnie Hill in 1928 which was believed to have been made by a professional photographer to be sent to relatives in Argentina.

It showcases the house, grounds and staff, as well as the fleet of luxurious cars including a Rolls-Royce Twenty complete with chauffeur.

Mr Fraser said: “As you will see, the brothers quite quickly accepted the advantages of petrol driven cars and some of these are unusual and interesting, especially those owned by Robert at Cairnie Hill.

“Numerous of the next generation are also listed among those who registered vehicles.

“I have managed to identify the cars in the 1920s archive film.

“All are petrol driven.

“Again, if spares were needed, a replacement would be made at the works, invariably superior to the original and more easily obtained than by order from Detroit!”

In 1959 Douglas Fraser & Sons was taken over by Giddings & Lewis from Wisconsin.

Dundee’s very first foray into the automobile world was the Dei-Donum in 1896 which was “a petroleum powered truck-like vehicle with rubber wheels”.

It was hailed as the first motor vehicle with “every part made in Dundee” but its maiden voyage revealed all sorts of defects and objections and it was towed away by horses and never seen again.

William Robertson and Sons, Bell Street, Dundee, then made motor tricycles, voiturettes and cars.

The brand name was Robertson.

The company began production in 1900 but fizzled quickly.

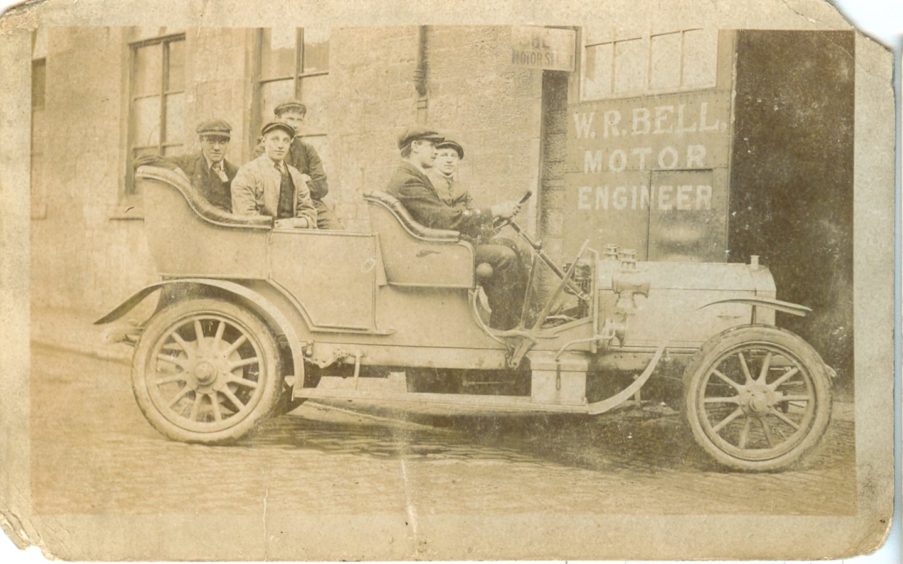

Elsewhere, from their plant in South Ward Road, Dundee, brothers William and Edward Raikes-Bell built eight Werbells from 1907 to 1909.

William and Edward drove their Werbell with a 4084cc water-cooled four-cylinder engine to the top of the Law — and there wasn’t even a road back then.

The brand was little known and soon disappeared from the market.

After the Werbells, the brothers moved to Forfar and began building charabancs — a sort of large open-top bus.

At the start of 1914 the business went bust and the next year William was badly injured when attempting to solder a petrol tank which suddenly exploded.

In Dunfermline the family firm of Michael Tod and Sons built one solitary prototype three-wheeler in 1897 in collaboration with local coachbuilders George Kay & Sons.

Local newspaper reports from the era said it was ahead of its time thanks to early Dunlop tyres and a capacity to reach 30mph, much faster than the law permitted.

For unknown reasons it never went into full-scale production.

In Laurencekirk, cyclemaker John Tavendale established the Mearns car firm in 1899 and changed the name to St Lawrence, but gave up in 1902.

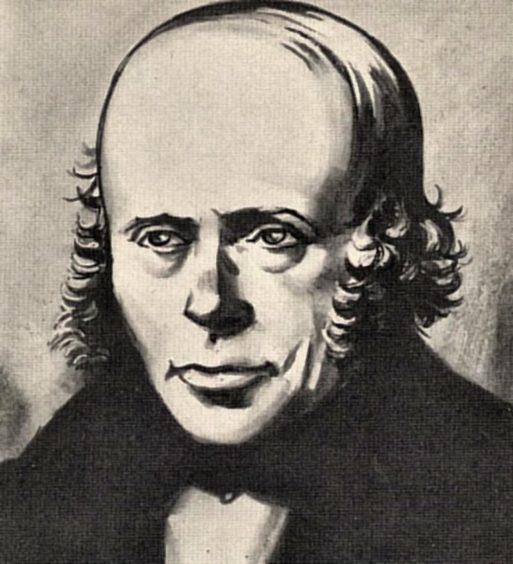

In Aberdeen, Robert Davidson pioneered the idea of electric transport back in the 19th century.

In an era before volts and watts had been dreamt up, Davidson found himself fascinated by the possibilities of electricity.

During this period, electricity could be generated, but not in a way that could be exploited as a practical electric motor.

Keen to try his hand at utilising electricity in a different way, Davidson set about constructing his own portable batteries and by 1837 had created his very first fully electric engine.

Two years later he held a public exhibition in Aberdeen where thousands travelled to see his invention.

Local historian Dr Kenneth Baxter from the University of Dundee said: “This was the east of Scotland’s chance to make a bid for a share of the car industry.

“It’s a shame that things did not take off or else a motor industry might have developed locally.

“I think there were quite a few people in Dundee and Angus who realised in the early 20th century that the motor manufacturing industry was about to take off and that motor vehicles would become increasingly important.

“Given the presence of several established and successful engineering firms in the area, it is no surprise that there were attempts to try to break into this new industry.

“Unfortunately these small scale efforts came to nothing.

“It is a pity, for had even one company’s efforts managed to take off then it is entirely possible that a car industry could have developed in the area.”

Nearly 60 Scottish firms ventured into car-making, and a handful survived for several decades.

The vast majority of car-makers were located in and around Glasgow, although Edinburgh, Ayrshire and rural Dumfries and Galloway also boasted several manufacturers.

Volume car-making did arrive in Scotland in 1963 when the Rootes group, spurred by the then government, opened the Linwood plant in Renfrewshire to make the famous rear-engined Hillman Imp to challenge the all-conquering Mini.

Rootes was taken over by US car-maker Chrysler, who later sold what was left of the Rootes empire to Peugeot.

Linwood was axed and its closure was a contributory factor to the eventual demise of the Ravenscraig steelworks at Motherwell.