William Abrams grew up in New York but a fascination with bridges inspired him to write a novel about the darkest night in Dundee’s history.

The book took him a decade to write and he credits the adventures of Thomas the Tank Engine for helping him get it over the finish line.

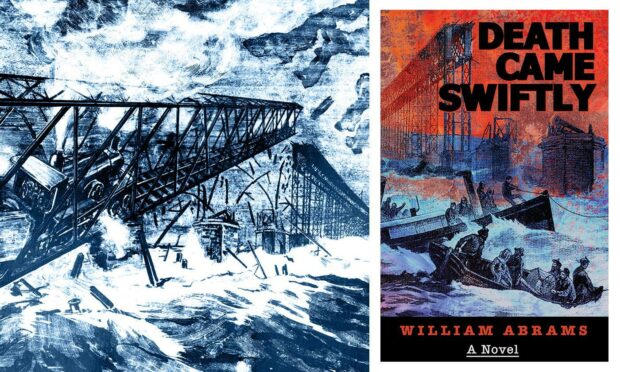

Death Came Swiftly is a fictional story inspired by the tragic history of the disaster and it has already won rave reviews after going on sale in the US.

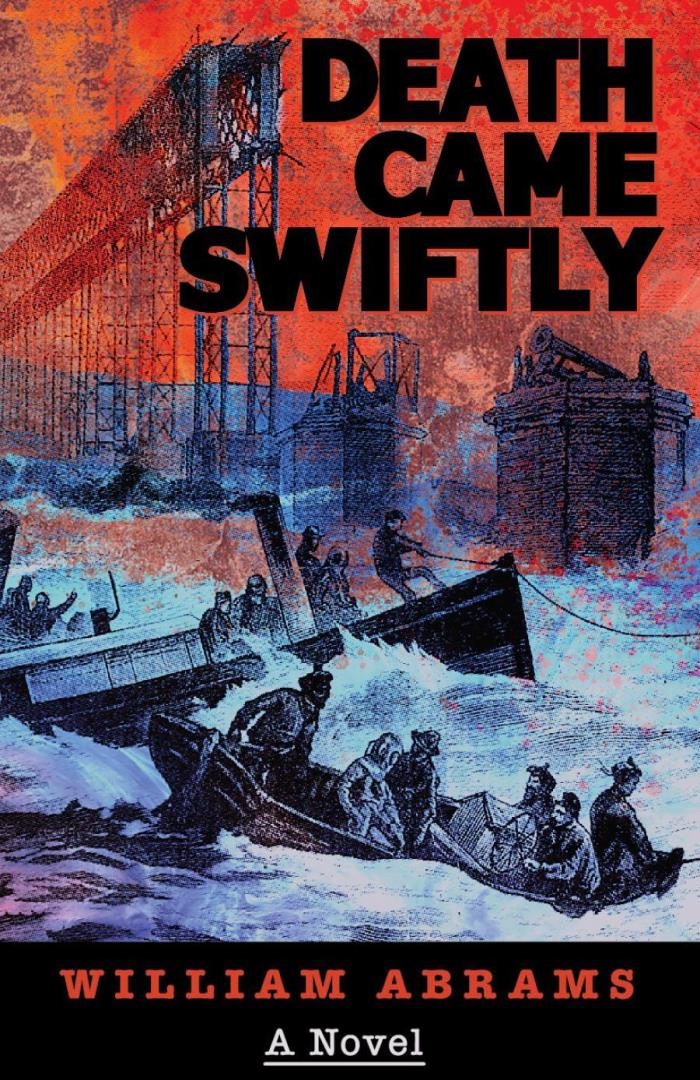

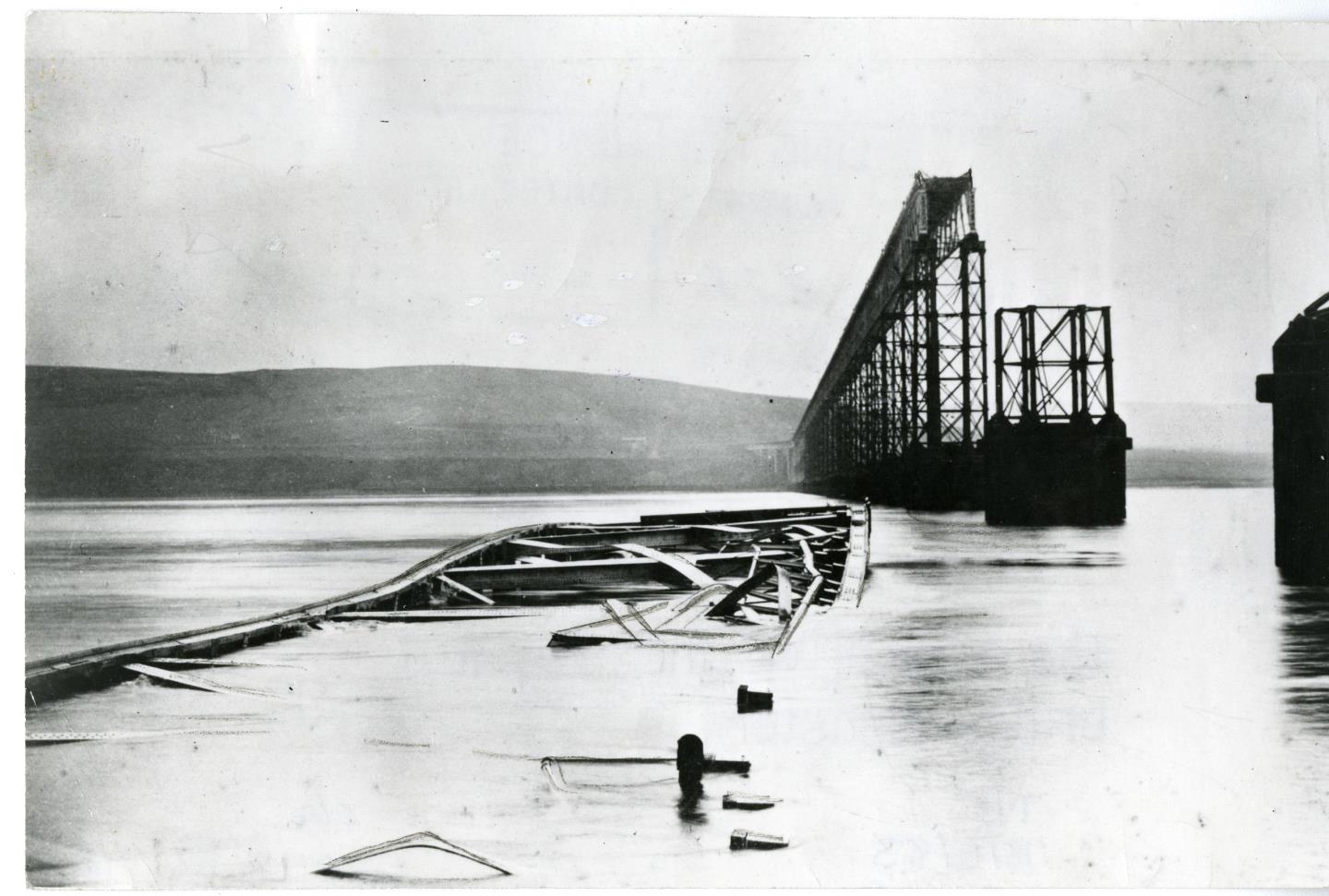

There were no survivors when the bridge collapsed during a violent storm in December 1879 with only 46 bodies recovered from the 74 known passengers and crew.

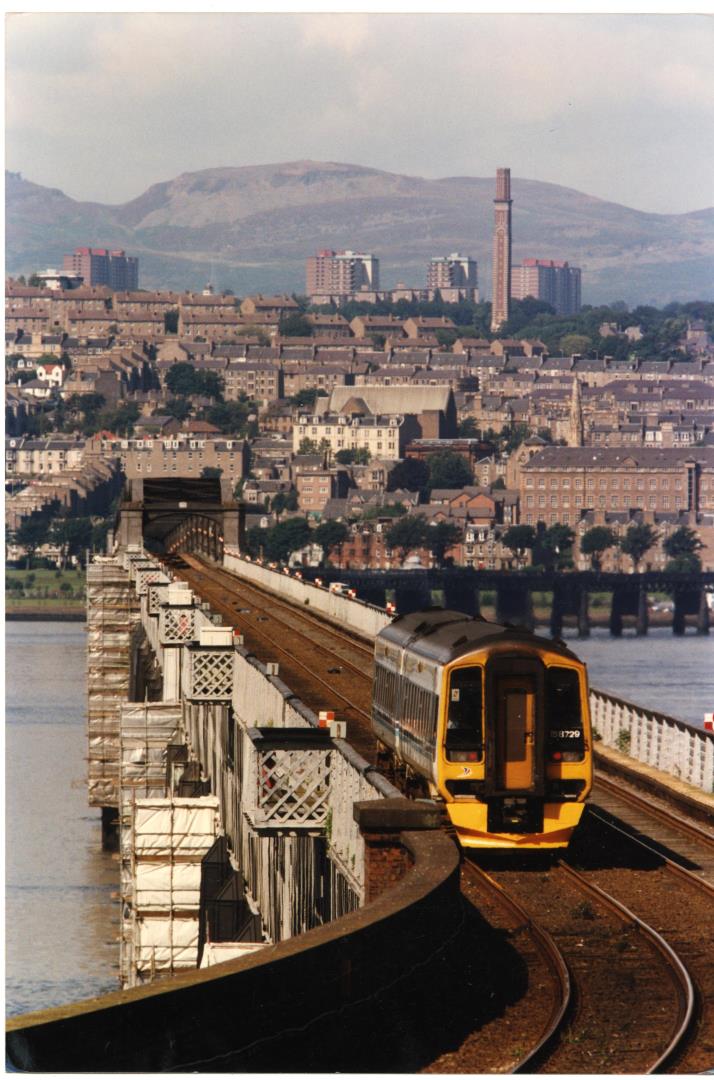

Crossing was a lifeline

Abrams is now the latest artist to be inspired by the tragedy.

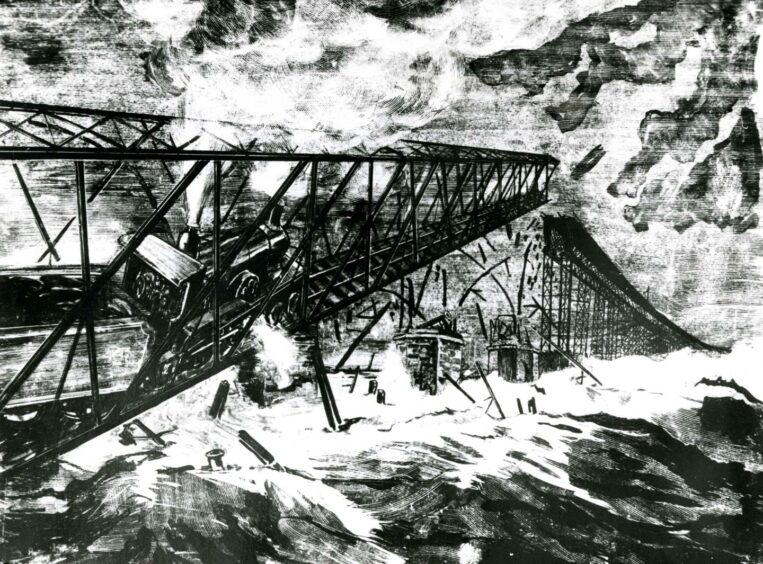

He said: “When the bridge fell, Dundee became a real focus of attention.

“People said it was the worst bridge ever built.

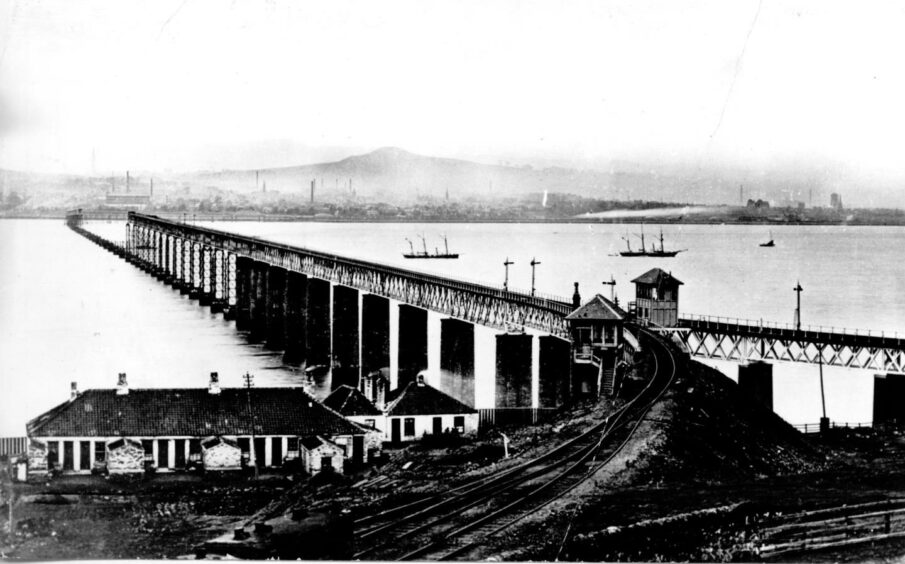

“But I tried to get it as close as possible to what was really going on at the time. The bridge is such a lifeline to the people of Dundee.

“I think it’s right that they know what really happened.”

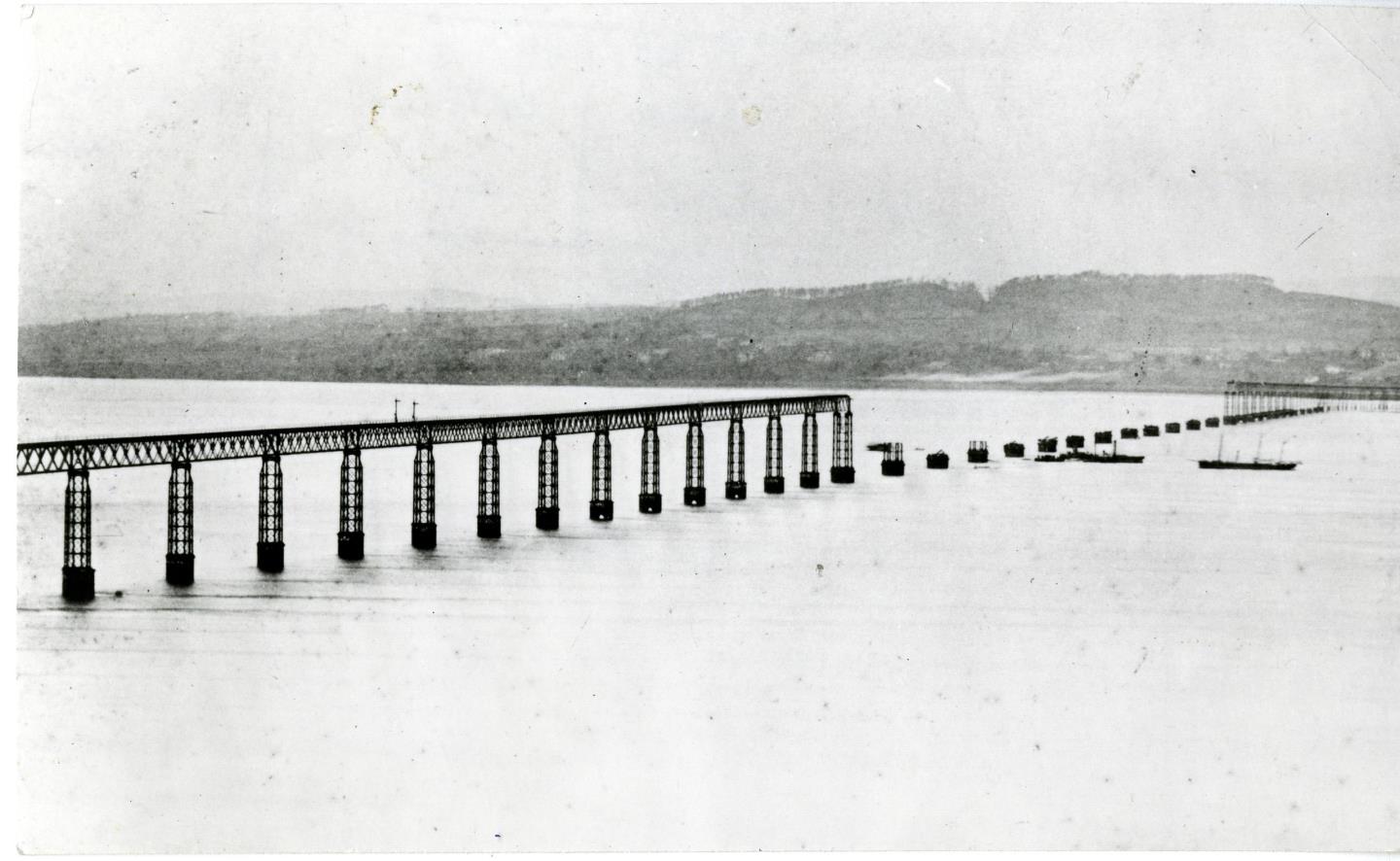

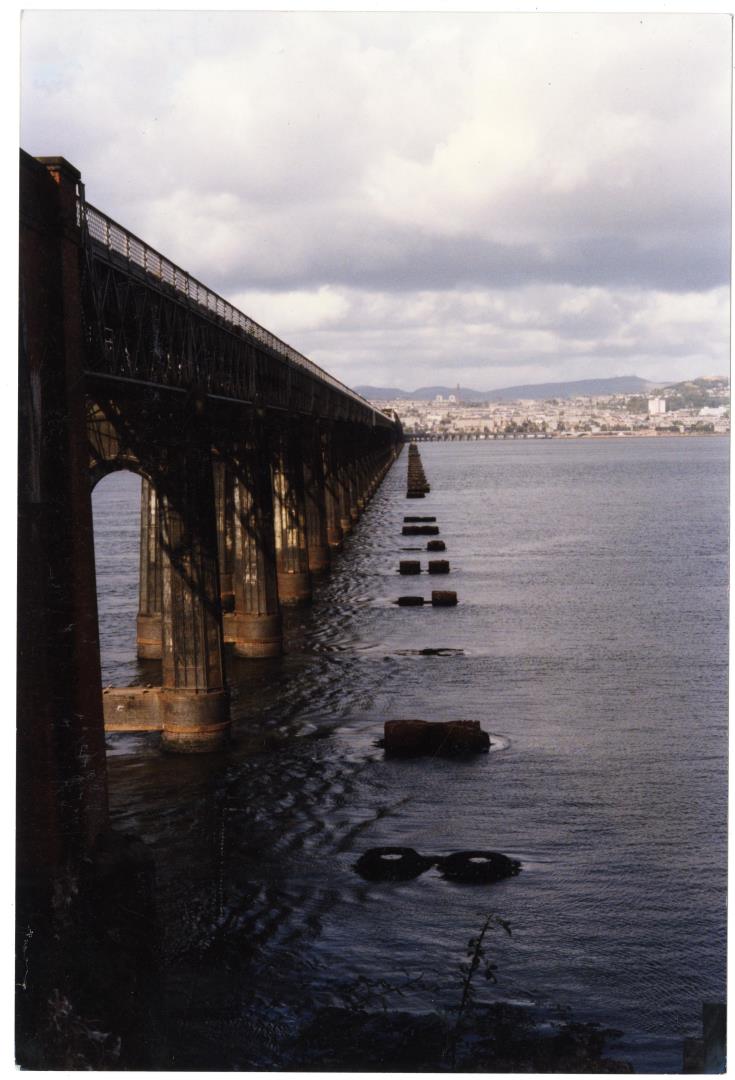

In time, a British Court of Inquiry would acknowledge that elements of the Tay Rail Bridge were not strong enough to withstand the force of the wind, leading to the failure of the supporting columns.

Along with the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, the collapse of the bridge only 14 months after its completion remains one of the biggest technological disasters of all time.

Tay Bridge disaster book focuses on two engineers

Abrams added: “There’s a lot that is tragic about the Tay Rail Bridge disaster.

“People have always said that the engineer made tragic mistakes and that was why it fell – but it was more that he was in over his head.

“These were the standards of the time. These engineers were encountering things they’d never seen before.”

Abrams referred to the use of cast iron to build the Tay Rail Bridge, a material that had already been outlawed in the US.

He said: “The weakest part of the Tay Rail Bridge was outlawed in another country. But not in Scotland. It was still common to use cast iron there.

“I don’t think we can blame the engineers when it was just what was done at the time.

“There’s always money to do it right the second time.”

Death Came Swiftly is set during the Victorian era, when railroads, bridges, and other feats of engineering were transforming everyday life.

Engineers were achieving a level of celebrity once reserved for poets and war heroes.

The story focuses on two engineers: one has committed his reputation to building bridges out of steel, a new material that has yet to be accepted by the British railroad establishment.

The other is a veteran engineer who has spent 30 years building railroads and iron bridges across Scotland and northern England.

Abrams was inspired to write his novel when he saw the pride that the people of Dundee have over the rail bridge.

He said: “Fifteen years ago I saw this programme on railroad history.

“They interviewed a man who had been working on the Tay Rail Bridge his whole life.

“He was so proud of his work, and to have been involved in a project like that.

“I hope the people in the area feel a similar pride for the bridge too.”

Other written representations of the Tay Rail Bridge disaster include Alanna Knight’s 1976 book A Drink for the Bridge, plus The Blood Doctor, by Barbara Vine, published in 2002, and a play by Kevin Dyer named The Bridge, staged at Dundee Rep in 2010.

Mr Abrams said his own novel took 10 years to write due to the extensive research he completed.

Mr Abrams love of bridges began during those early years in New York.

He said: “It was my childhood; growing up around some of the greatest bridges in the world.

“That then developed into an interest in trains – where I came across the story of the Tay Rail Bridge.

“How could I not have heard the story? It’s one of the greatest bridge disasters of all time.”

Abrams’ studied modern European history at university, which enabled him to follow his childhood dreams and learn more about the history of science and technology.

His stepfather was an engineer and worked on power supplies for the local subways.

He believes bridges are one of the greatest ways to study Scotland’s history.

He said: “In places like Fife, you can see three bridges across the same stretch of water, all built several years apart – and it’s the best way to see how technology has changed in that time.”

Mr Abrams is currently the contributing editor for Ranch and Coast, a local San Diego magazine, where he now lives with his wife, after eloping from New York.

Although now covering local events for San Diego’s prominent military population, he was previously employed as a technical writer.

He wrote user guides and manuals for different technology.

This is why he believes the technical side of the novel, which explains the workings of the bridge to the reader, is still accessible.

He said: “I think this novel is going to feel familiar to a lot of people in Dundee.

“Not just because of the bridge – a lot of people will have grown up with TV programmes like Thomas The Tank Engine.

“It’s a familiar concept to people – steam engines and bridges. This is the grown-up version of that show.”

Mr Abrams also credits the kids’ show for making sure his novel got completed.

“I watched that show with my kids, and I was really inspired by the line ‘thank you, Thomas, for being a useful engine’.

“It made me finish the novel.

“The last thing anyone wants to be is a useless engine.”

More like this

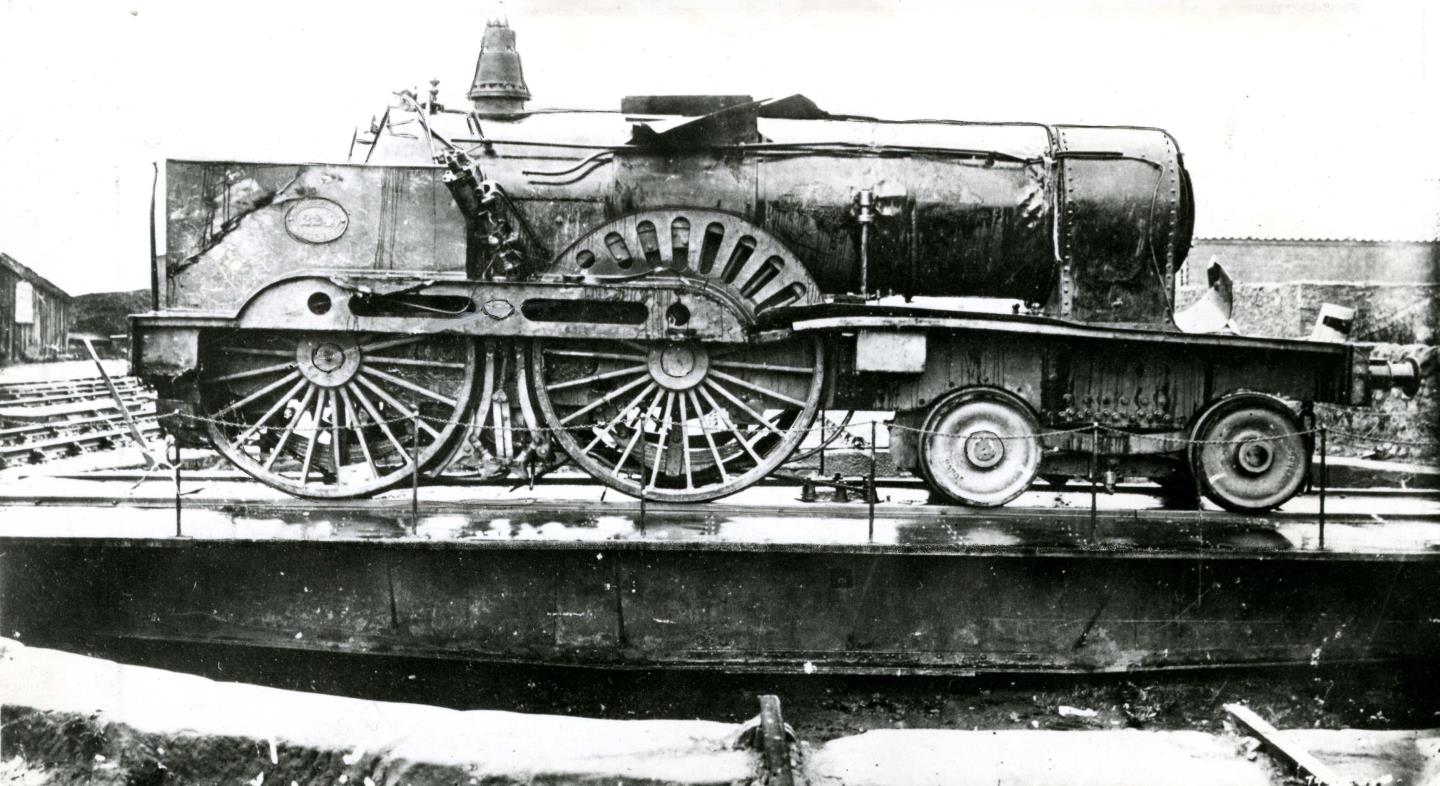

Remembering the ill-fated engine which plunged twice into the icy depths of the River Tay

India’s Golden Bridge will forever be linked with the Tay Rail Bridge Disaster