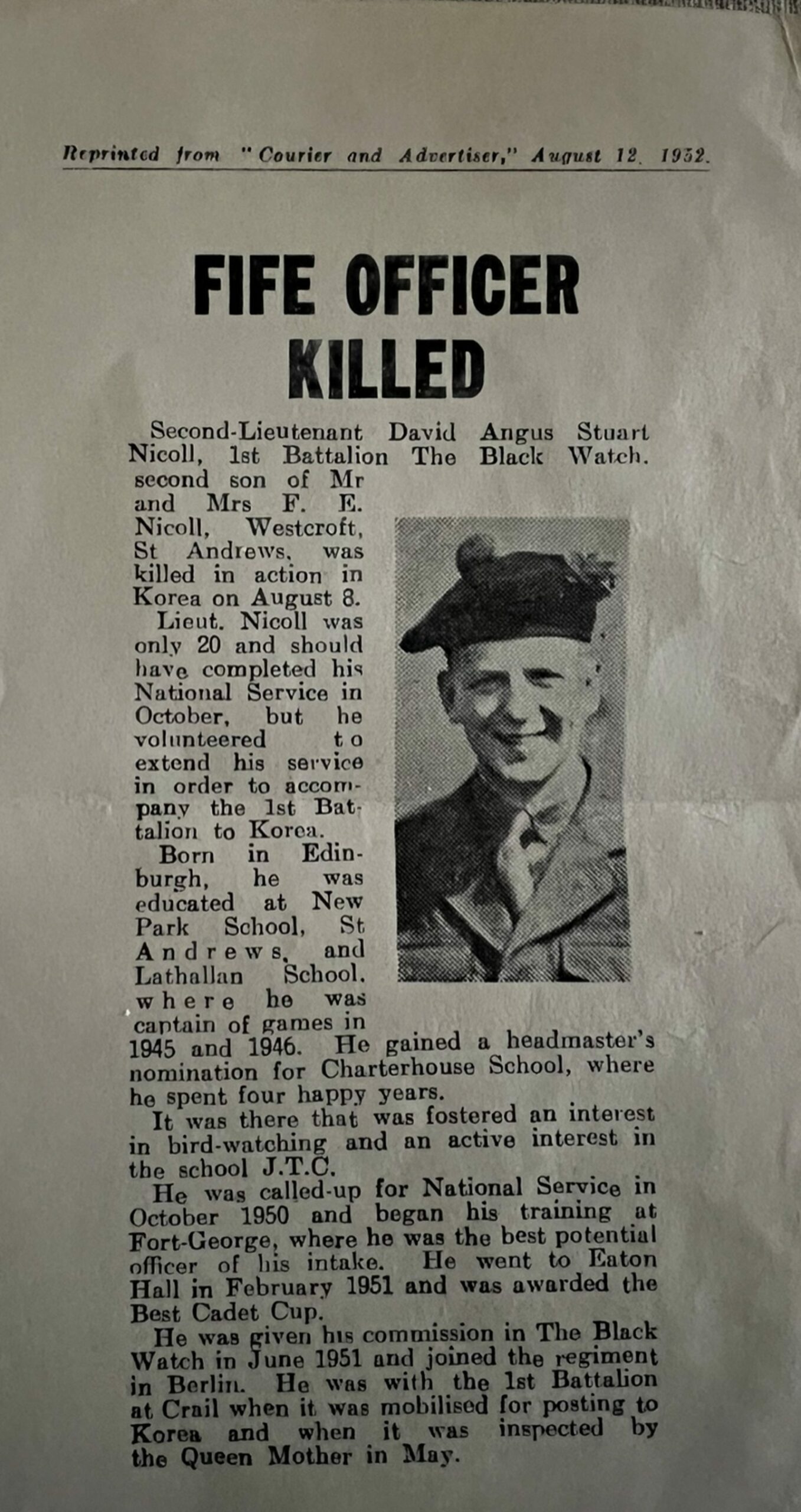

Meet my uncle: he died in a forgotten war that ended 70 years ago.

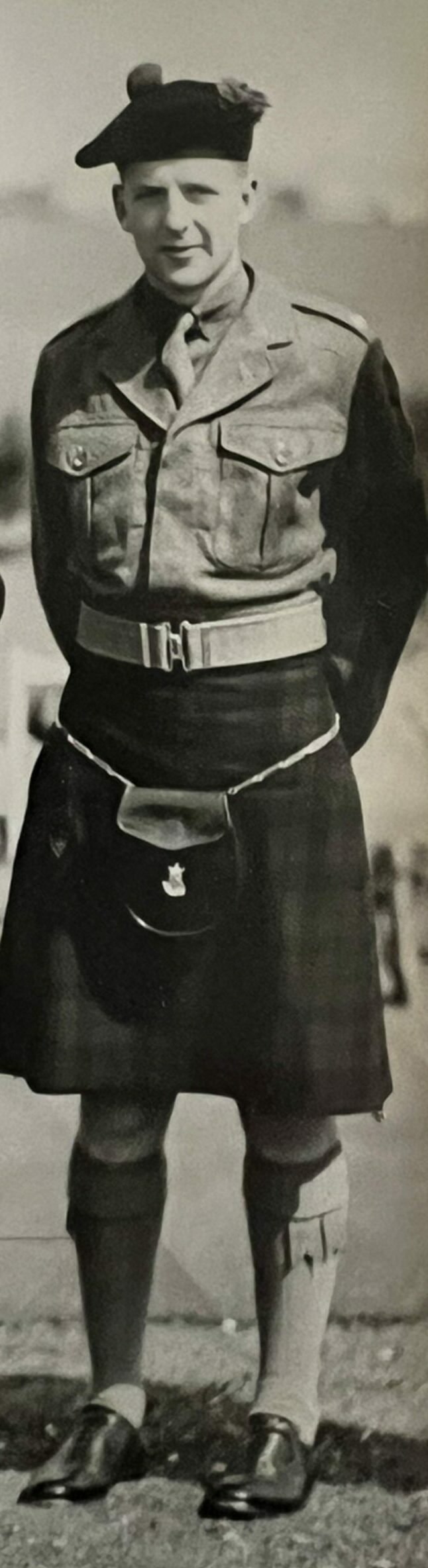

He was a young man, not just a name on a war memorial.

John Nicoll was home alone in Wardlaw Gardens, St Andrews on August 9 1952 when the telegram arrived.

“Deeply regret to inform you that your son was killed in action in Korea.”

For several hours John had to live with the knowledge that it would fall to him to tell his parents that his brother, their third child, would never be coming back to Scotland.

Second Lieutenant David Nicoll, who was 20, was one of 236 Scots killed in the Korean War which ended with an armistice on 27 July 1953.

He had nearly completed his National Service with The Black Watch 1st Battalion when, in March 1952, he volunteered for a five month extension to go with them to Korea, deferring his place at Cambridge.

Perth museum told St Andrews teen’s Korean War story

He was, effectively, on his gap year. He died exactly two weeks after turning 20, the day the platoon was due to leave the front.

The Korean conflict lasted three years and left the Korean peninsula much as it had been before it started: divided at the 38th parallel.

The Black Watch was one of three Scottish regiments sent out to join UN forces from over 20 countries in defending South Korea after its invasion by the North in 1950.

In that same year, National Service was increased from 18 months to two years.

More than half of Scots serving in Korea were, like David, on National Service, with no intention of becoming regular soldiers.

Last winter The Black Watch Museum in Perth put on a small display which told the story of the Korean war and David’s part in it.

Sent out with his platoon to mend the wire round a minefield, he had ordered his men to keep back while he made a solo reconnaissance.

The record shows he was killed by a wound to the head, presumably by a sniper.

The museum displayed his red hackle, his last letter to his parents, and that fatal telegram.

David Nicoll is named with the rest of the fallen in the pagoda that forms the Scottish Korean War Memorial at Torphichen in the Bathgate Hills near Linlithgow.

His name is also carved high up on the Armed Forces Memorial in Staffordshire, which records those killed whilst serving since 1948.

The military is very good at remembrances, but it means that those who have served are forever seen as soldiers.

Earlier this year I gained a greater insight into the real David through five letters he wrote to his older sister, my mother Elspeth.

Discovered while clearing out my late father’s house in the Borders, they are dated between March and August 1952, from embarkation on the troop ship HMT Empire Orwell to his last note from the front line.

Young man on brink of life

Along with a collection of watercolours of Argyll landscapes, and exquisite bird sketches made during a teenage trip to the Western Isles – he was a keen birder – they reveal much more about a young man on the brink of life.

Together they chart his unwitting progress from youthful life to early death.

On March 16 he writes about his decision to sign up: “You may have heard of my madness, but it is only five months which is just enough time to get out there and come back. There is absolutely no possibility of signing regular.

“Dad doesn’t approve of my decision. I didn’t really expect him to!”

In the letters that follow, he continues to be nonchalant about his service.

Although nominated by the NCOs as the best potential officer, he loves to give his sister the impression that it is all a bit of an adventure – perhaps to reassure her.

By June 27, he is five miles behind the line, but still being chipper for his sister, even though the big guns are on the other side of the hill.

He gives a description of a typical day, involving “bashing up and down hills in full kit” and “demonstrations on mines and booby traps – all rather tiring when the temperature reaches 100F.”

On July 6 there is a casual mention of taking a recce party “up the line tomorrow” and being there “until August sometime”.

“Of course this is all secret,” he confides, “but I am told letters are not censured.”

Even in his last letter, when they are “the furthest-forward platoon in the Commonwealth Division – right at the sharp end”; when it has rained for four days solid and everything is caked in mud; when the water is dripping into his dugout ruining the previous long letter he had written to Elspeth so he has to start one again on borrowed paper, he takes his military service lightly.

“All that happens,” he writes, “is that the company commander gives me a severe rocket every now and again for general inefficiency,” adding cheerfully, “that’s just one of the things that keeps life going.”

Four days later he was dead.

Along the way he charts both the surprising luxuries and the discomforts.

His longest, penultimate, nine-page letter to Elspeth was written sitting on a beer crate by candlelight as the heavy seasonal rains start again, turning everything to “two to three feet of mud”.

There are detailed descriptions of daily routine, which according to this Second Lieutenant includes a great deal of platoon inspection, particularly checking for blisters and whether socks need washing and darning.

Throughout the letters there are glimpses of everyday interest in getting back to a social life and meeting girls.

On the ship out he enjoys dancing with a secretary from the Hong Kong war office and always asks for news of girls back home.

His final thoughts in his last letter are for the girls in Edinburgh.

He concludes: “This has been an experience all right but I won’t be sad to board the ship again.”

David is buried in South Korea

He never embarked on that ship.

No part of David ever returned to Scotland.

He is buried in the United Nations Memorial Cemetery in South Korea.

We will never know how his life might have turned out had he made it home to Scotland.

David could even now be a sprightly 91-year old, still bird-watching and painting.

Of course, all sorts of life’s other disasters could have got to him.

But artistic talent is rarely lost and the qualities noted when he was posthumously awarded the Elizabeth Cross and scroll at a ceremony in Ayr in 2011 – his “charm and good manner” and “constant unselfishness which never lost him a friend he had made” – are also likely to have been consistent over a lifetime.

RIP David, and all the other young Scots who died in a futile, faraway war.