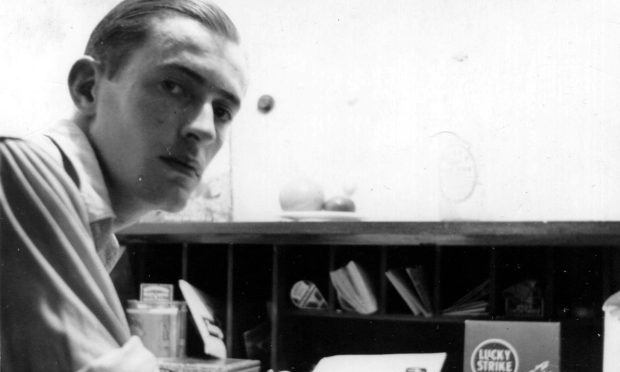

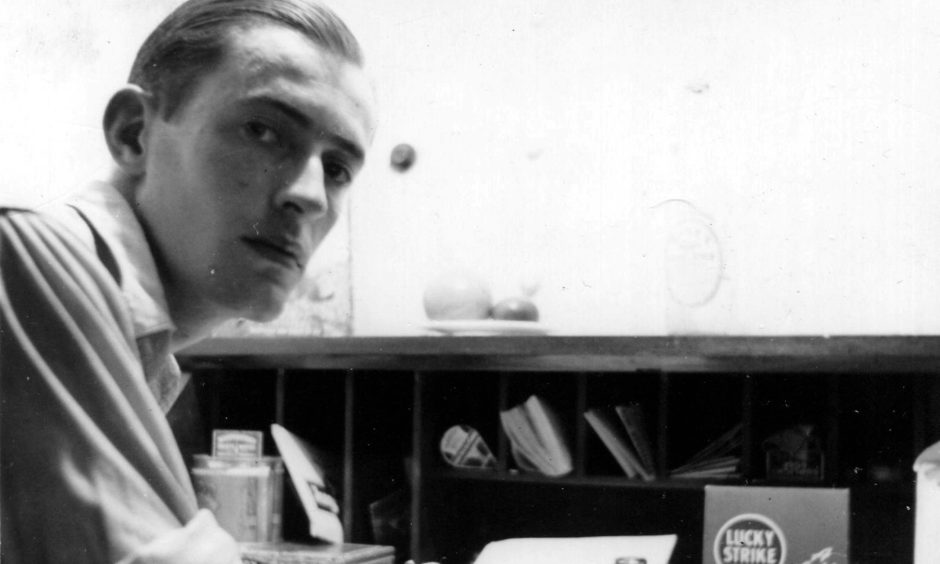

Alex Anderson was just 19-years-old and fresh out of Dundee’s Wireless College when he bade farewell to his rural Perthshire home and embarked upon a life-changing voyage of adventure and self-discovery.

The son of a local schoolmaster, his maiden voyage took him to the vast Antarctic Ocean as part of a six-month whaling expedition with Christian Salvesen of Leith.

However, the course of his journey took an unexpected twist on the return voyage.

Facing up to the outbreak of the Second World War on the high seas

With the Second World War engulfing Europe and beyond, Alex found himself caught in the crosshairs of Hitler’s U-boats as they prowled the Atlantic in packs, searching out allied merchant shipping.

Over the next five and a half years, he was thrust into the treacherous North Atlantic convoys – the UK and allied forces’ lifeline of essential supplies including oil, military vehicles and aircraft.

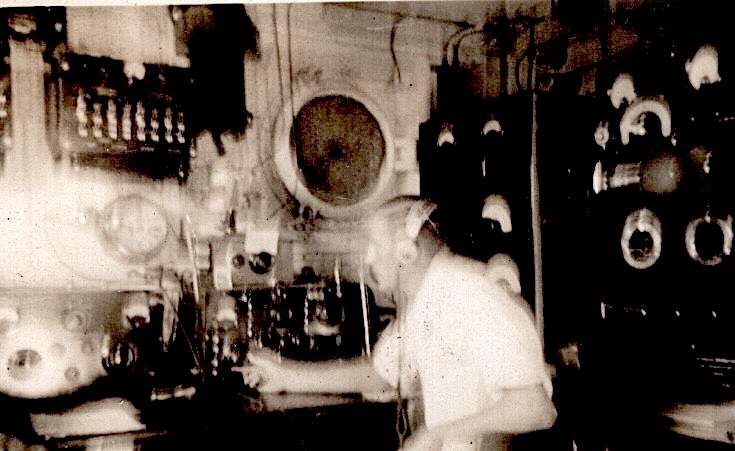

During ‘The Battle of the Atlantic’ – the Second World War’s longest-running campaign – Alex sent and received coded and sensitive communications as a de facto Royal Navy officer facing the daily perils of submarines, mines, and Luftwaffe bomber attacks.

Tragedies too, become all too commonplace with four of the seven ships he served on being lost to enemy action.

Yet, amid the chaos, he experienced moments of humour, hospitality abroad, and even unexpected romance albeit brief.

From the shores of the United States and Canada to the vibrant landscapes of the Caribbean, West Africa and the Mediterranean, before finally entering northern Europe, he experienced both the trials of life at sea along with brief but welcome respite on foreign shores.

Now, some 80-years after the loss of 30,248 merchant seamen during the Second World War – a death rate proportionately higher than any of the armed forces – Alex’s journey from Merchant Navy 3rd Radio Officer to a seasoned 1st (Chief ) Radio Officer is being told in a newly published book.

‘Hunter to Hunted, Surviving Hitler’s Wolf Packs’ (Diaries of a Merchant Navy Radio Officer, 1939-45) has been released in both paperback and e-book versions.

The first-hand account takes readers right onto the deck and into the radio room through six years of the treacherous war at sea.

When and why did Alex Anderson write his book?

Alex actually wrote the memoir 25 years ago.

He battered it out on an old typewriter at a time when he had been misdiagnosed with bowel cancer.

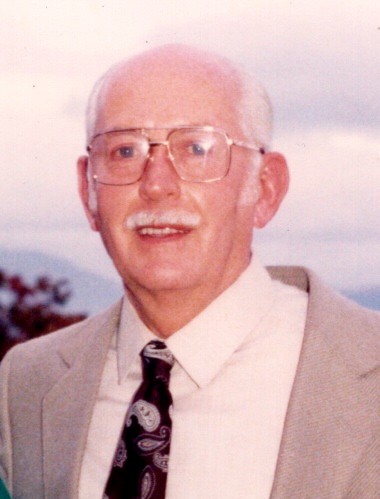

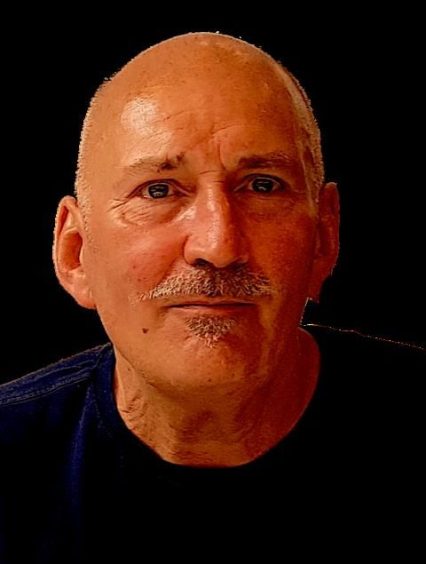

More than 20 years after his death in 2000 aged 80, however, Alex’ eldest son Bill has now edited the book and had it published in tribute to, not only his father, but to all the mariners whose courage and resilience shone through during the war years.

Father Alex didn’t talk much about the war, says son Bill

Speaking to The Courier from his home in St Madoes, Perthshire, Bill, 65, a retired DCI and special branch officer with Strathclyde Police, explained how it was his father’s dying wish that his experiences should be published.

“My father didn’t talk too much about the war,” said Bill, who grew up in Crieff.

“But he had a big box of notes, diaries and photographs and lots of memorabilia stuff as well which helped him remember.

“It had been his desire and wish to write down his stories for decades.

“He just never got round to it.

“Then when he was misdiagnosed with bowel cancer – which came on quite sudden – he typed it up.”

Bill explained how he tried to get a publisher interested at the time.

However, it “fell on deaf ears”.

Some publishers gave good advice about editing and layout, suggesting it should be written “less like a diary”.

Bill made a start on re-arranging it.

But he was working full time in Glasgow at the time, and didn’t manage to do it before his dad passed away.

“Ultimately my dad’s last wish was ‘will you continue to try and get it published’,” said Bill.

“I don’t actually know what the great desire was to have it published. But that was his only kind of wish.

“I’ve carried that for the last 25 years, and a bit like him – it was one of those things – ‘I’ll do it when I’ve got time’.

“It was basically Covid-19 and lockdown that got me into it because I had time on my hands.

“It’s still taken the last few years to take it to where it is now.”

What led Alex Anderson to go to sea in the first place?

Bill’s grandfather had been a schoolmaster and lay minister who moved around Perthshire.

They lived in Methven when his father was at Perth Academy.

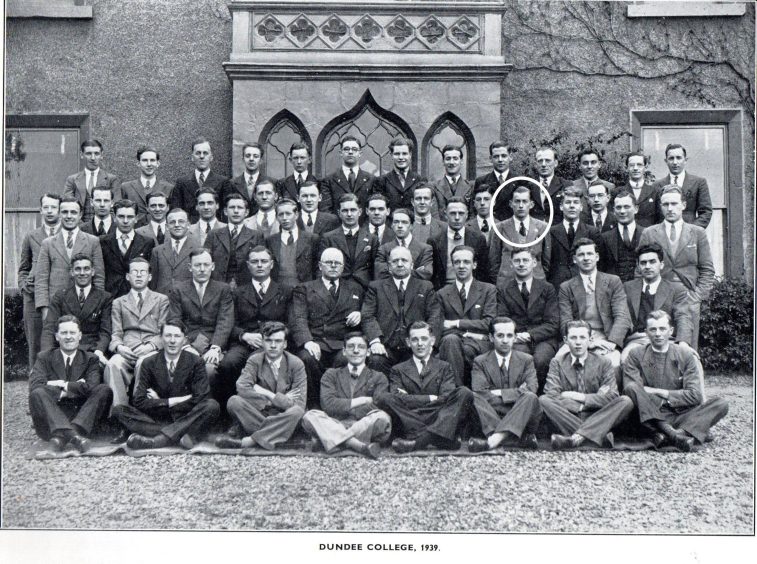

From there he went to Dundee Wireless College in 1939.

Bill explained that when his father was at school, and before he went to wireless college, he worked at a wee shop in Perth that sold and repaired radios.

He also had a “thing about seeing the world”, so going to see was perhaps a natural progression.

At wireless college, everyone who passed out in the class of 1939 did so with a first class diploma.

After graduation, and frustrated about delays in getting a role, he toyed with the idea of joining the RAF.

However, Christian Salvesen ultimately came along and offered him his first trip to the Antarctic.

By the time he returned, the war had really taken off.

As a radio operator, Alex became a de facto Royal Navy officer.

Bill Anderson learned more about his father after reading memoir draft

Bill said that when he was growing up, his father generally didn’t talk about the war but would occasionally mention it in passing if something came on TV.

He remembers watching a film once with his brother.

It featured a military unit trying to send a message to HQ using Morse Code.

As the character tapped out the message, their father, who was also watching, spoke out the message just seconds before the characters on TV said the same thing.

“We were like ‘where the bloody hell did that come from?’,” laughed Bill.

Bill said his father would mention ships being lost and losing colleagues.

But he never learned details until he first read the memoir.

“Basically what it was the level of detail in there,” he said.

“He was really expressing what it was like to be at the Battle of the Atlantic.

“I knew he was Merchant Navy and in the North Atlantic convoys.

“You’d think in the merchant navy – ‘well it’s not the same as the Royal Navy or the US or Canadian navy’.

“They had minimal defences on board.

“But what I realised after reading his memoir was they really were in the thick of it.

“It was the merchant shipping that was the target to cut the supply lines.

“Only occasionally did they have any armed escort, and they’d only have them for short periods of time.”

What else did Bill find as he looked through his father’s photographs and papers?

As he helped re-shape the copy, Bill started looking through his father’s old photographs.

He even found a People’s Journal article where he featured in 1940.

Amongst them he found his medal ribbons.

But his father had never bothered to get them, which he thought was a “shame”.

Bill wrote to the Merchant Navy and managed to get them for him.

When they arrived, he had them mounted.

He thinks it pleased his father.

What would Alex Anderson think of the book?

Bill thinks that if his father was still alive today, he would be “delighted” to see the book published – albeit “slightly annoyed” it had taken so long.

“I suppose in fairness he would say it took a long time for me to get it written,” he added.

“He never had the opportunity to show what he’d done to his own father who had basically handed him three school jotters when he set off in 1939 and told him ‘you must keep a diary.

“Make the most of it and keep a record of the things you see and do’.

“The Antarctic was a baptism of ice.

“But the Atlantic convoys was a whole new baptism of fire.

“He never did say why he was so keen to get it published.

“But the inkling I have is he wanted to get it published on behalf of those who didn’t make it. To say ‘this is what it was like’.

“There were cabin boys in their mid to late teens. He was 19.

But some of these boys looked really really young.”

Bill added that 80 years on, the stories today seem to “cross the generations”.

People he’s spoken to from a Merchant Navy background say there are few stories published about what really happened.

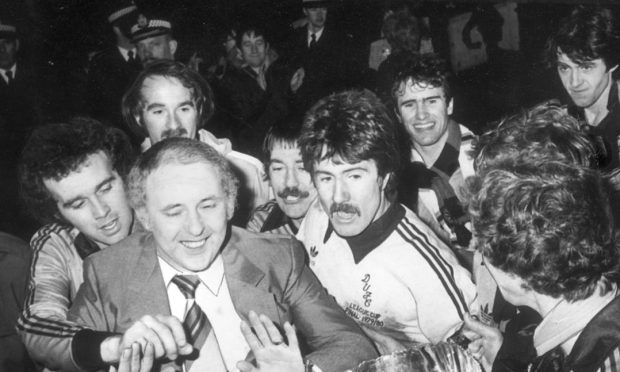

For lots of people Bill’s age and younger, however, his father is probably “mostly remembered” for running the shop where people spent money on records.

How to read Alex Anderson’s memoir

Hunter to Hunted, Surviving Hitler’s Wolf Packs’ (Diaries of a Merchant Navy Radio Officer, 1939-45) is available in paperback (£12.99) and e-book (£3.99) formats (https://amzn.eu/d/4jl9LtK)

Conversation