For Joanna Bowman, returning to the Dundee Rep is like stepping back in time.

“I used to come here as a student at St Andrews, back in 2013,” smiles Joanna, 30.

“It was before The Byre had reopened so Dundee Rep was my local theatre. I remember getting the 99 bus through all that beautiful countryside and across the bridge.

“We’d come to the theatre or to see films at the DCA. And have nights out in Klozet!”

Now, instead of the main entrance, London-born Joanna leads me through the stage door of Dundee Rep, where she’s been coming to work every day for the past few weeks as the director of John Patrick Shanley’s award-winning play, Doubt: A Parable.

“This is my first time back at the Rep as a director, so it’s really exciting,” she says.

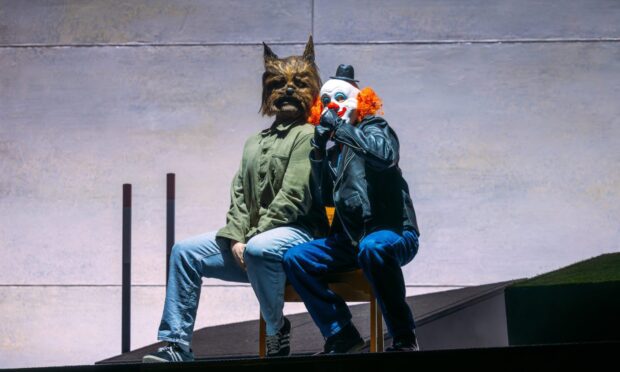

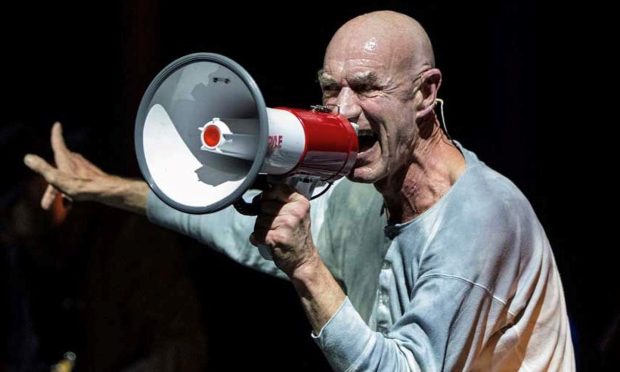

The play itself (which was also adapted into a 2008 film starring Meryl Streep and Philip Seymour Hoffman) unfolds against the backdrop of a Catholic school in the Bronx, in 1960s America.

Sister Aloysius, the formidable headteacher, levels a serious accusation of improper relationship with a pupil against charismatic priest Father Flynn. He denies this.

The rest of the play follows their battle of wills and asks the question, of its characters and its audience: “What do you do when you’re not sure?”

In our times of AI-generated images, “fake news” and cancel culture, the question is prescient.

So I sat down with Joanna to ask her 5 important questions about directing Doubt in 2025.

Did you draw from any real-life inspirations when directing this production?

It’s a good question, and hard to answer because I don’t have some big pronouncement to make with it.

This play is about complicated things; things that are really resonant and really essential now.

While it is absolutely about the question of child sexual abuse within the Catholic Church, it’s also a framework for us to consider uncertainty, and how we bear it in our day-to-day lives.

What kinds of day-to-day doubts spring to mind?

A particular thing about working in theatre is that every time you do a new show, you meet dozens of new people. And that’s one of the best things about the job.

But when you have a doubt about someone’s motivations, or whether you even like someone on a personal level, a personal distrust can become a political or material one.

I think there’s interesting stuff in the play about what we do when we don’t like people that everyone else likes. Because that’s a really weird feeling.

I’m sure everyone has experienced that at some point in their life.

You know, when you meet your best friend’s new partner, who everyone loves, and you’re like: ‘I don’t know if I do like you’ – that makes you distrust yourself. ‘Why don’t I? I’ve got no reason not to’.

Maybe dolphins feel like that too, but to me that feels uniquely human.

Do you think we live in a more suspicious culture now than in the 1960s, when the play is set?

The ’60s were sort of the birth of modern culture in terms of engaging with the institutions that had governed western life, and with authority becoming a less appealing concept.

The playwright talks about the world going through puberty in the ’60s. And I think that’s true. I think I think you can sort of trace back a lot of how we function today to that time.

One of our castmates (Ann Louise Ross as Sister Aloysius) remembers the ’60s.

And I think, after our conversations, there are more similarities between then and now, in terms of sort of turbulent times and changing times, than we might think.

The tagline for the play is “What do you do when you’re not sure?” – what’s your personal response to that question?

For me that is the thing that sums up this play, and it’s why the play is so interesting. I think uncertainty – doubt – is a really useful thing.

If you if you think that you know something, it means, to me at least, that there’s no space for curiosity.

Admitting to not knowing or being unsure about something creates space for you to work towards certainty or knowledge.

Certainty can make you lazy.

That isn’t saying that I don’t have morals or principles or beliefs that I absolutely would stand by. But I think certainty is easy.

And all you’re saying with the phrase “I don’t know” is “I don’t know yet”. You’re not saying “I will never know”.

I would much rather live in a world where people are able to admit what they don’t know, or that they don’t know, and that we can bear that.

In particular, social media benefits when people disagree. It doesn’t benefit when people say: “I don’t know”. We live in a world where where our thoughts are monetized, these are platforms thrive on engagement.

And engagement is much easier when when people are ‘knowing’ something – whether disagreeing or agreeing.

Whereas uncertainty can’t be distilled into 280 characters.

How do you persevere in the face of self-doubt?

I think you have to have faith that things are worth doing. And I really believe that theatre is the best thing we’ve ever come up with as a civilisation, and that’s why I spend my life doing it.

I also have faith that my actors are going to go out there and do a stonking good job.

I have faith that the creative team and a technical team, and people in the workshops and the people in the paint room and the people in the rehearsal room are all going to bring their best selves in this production.

And I know what I want to say. I believe this play is good. That’s how I get beyond any self-doubt.

Doubt: A Parable is at Dundee Rep from Saturday April 19 to Saturday May 10 2025.

Conversation