As project leader at Front Lounge – an organisation established in 2001 to deliver activities for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds in Dundee – Chika Inatimi is no stranger to dealing with inequalities. However, as a black man, he is also no stranger to prejudice. Here, he shares his story with Michael Alexander.

My name is Chika Inatimi and I am a black man. The world is in a lot of pain at the moment.

Uncertainty prevails, apprehensive of the future persists. Why? A quirk of nature coupled to our own very human behaviours has produced a global pandemic which has challenged us in ways unimaginable. The virus has not respected creed, race, class, gender, age; it has been one of the most remarkable social levelling experiments ever encountered. Everyone is affected.

It is worth noting that despite the fact that everyone is affected we have not all been affected the same.

For some of us the resulting lockdown has been like an extended vacation, and for others a recurring nightmare from which they cannot wake.

There have been some extraordinary acts of community togetherness, braveness, kindness. There has also been a desperate spike in suicides, suicide attempts, and domestic violence.

No section of society has been immune from the Covid-19 disease.

It is striking that the greatest burden of excess deaths caused by the disease has been borne by the very poorest in our society. Significantly more so. Does that mean we do not care about the poor in this country?

And a picture is emerging in the UK of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) groups having significantly higher probability of developing and dying from COVID-19 compared with other ethnic groups.

Is this evidence of institutionalised racism? A kind of systemic default in everyday life and culture that leads to BAME groups getting the thin edge of the wedge? Again? And again? And again?

We were just beginning to wonder about all this then bam!

A black man was arrested by a white police officer – something that happens all too frequently in America – with the police officer’s actions resulting in the death of the black man. It was all caught on camera.

America saw and erupted. Now America burns. Again. This is truly shocking and whether you agree with the rioting that the death of George Floyd has sparked it is very hard to argue against the pent-up fury and rage they point to.

It’s burning over there, but that couldn’t happen over here. Could it? We don’t have a racism problem. Do we? And what about Scotland? We are alright, aren’t we?

I will respond to that question by recounting a personal story.

My parents left Nigeria in the early 1980’s and resettled in Merseyside with a brand-new life. In fact, they fled after being tipped off that a mob was coming to kill us.

It was particularly painful because my father, indeed my whole family, had spent much of our time in Nigeria looking after those less fortunate, doing good works and improving people’s lives.

We were the wrong ethnic group in the wrong place and had to go. We were also Christians in the Muslim north.

There I was a black child amongst those who I believed to be my own and I was not wanted. The memory of that emotion has stayed with me throughout my life.

The perfect contrast of this emotion was a prior experience. My mother became pregnant at university shortly after getting married. Her choices were to abandon her medical training and become a stay at home mum or send me back to Nigeria to be looked after by relatives. She did neither.

A kindly couple who had taken my parents in their hearts decided to look after me so my mother could continue with her studies. I should add that this kindly couple are white. The context? It was the 70’s, it was Dagenham, and for those of you who can recall it was a time when it was not easy to be BAME in the UK.I call this kindly couple mum and dad to this day. Their children are my brothers and sisters. We were a reconstituted family before reconstituted families were a thing. I grew up without any sense that I was different, even though it was glaringly obvious that I was.

This experience has formed my character, my world view, and it continues to prove to me what is possible. It stands in stark contrast to what I encountered some years later in Nigeria with my birth parents.

In my adult life I chose Scotland as my home. I count Dundonians as my people. I have worked tirelessly for social justice in this land. Strangely in the middle of last year, I experienced something similar to what I once felt in Nigeria. A dislocation. A sense of unbelonging. I felt like I really wanted to leave. Why? The growing clamour for Scottish

independence.

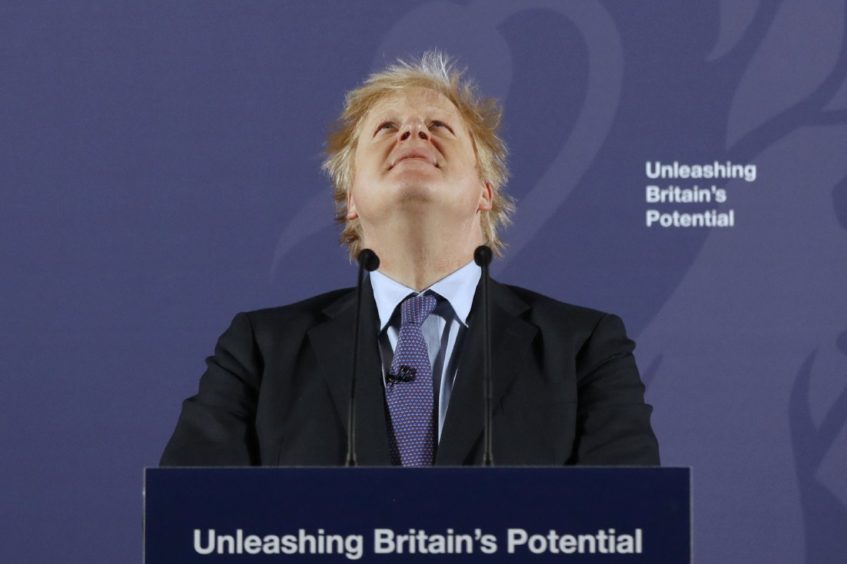

Again. Brexit. The Home Office hostile environment policy. The decimation of public services over the past decade. The rise of the food bank. The results of the last general election.

I think all these significant moments in the life of our society all keyed into a growing sense that my voice, my experience, my perspective was inconvenient, didn’t fit, wasn’t valued. I felt marginalised. The echo of a childhood memory that saw my family flee to make a new life in a new land.

The truth is that there are countless thousands who feel this alienation.

Race is a factor but this goes way beyond that. It is no accident that the suicide rate amongst young men in particular, has risen significantly of late. We are a society that is not at ease with itself. And Covid-19 has very much thrown another log on the pyre of our discontent.

I mourn the death of George Floyd. It is a human tragedy. As we watch Britain respond to what is happening in America, there is a clear message coming through: 50 years on from the 1970’s and it is still not easy to be BAME in the UK.

But my sense of alienation has nothing to do with America. We have seen just under 40,000 confirmed deaths of Covid-19 to date and this number continues to rise each day.

I am frustrated that I get no real sense that anything will fundamentally change in our society to transform the inequality underlying those 40,000 deaths.

I also wonder why we are not en masse marching on the streets demanding justice for these 40,000. They did nothing wrong. The horror show in our care homes. How can we have allowed that to happen in one of the richest nations on the planet?

There is latent rage, a building frustration. People are tired of not being heard or feeling like what they need or want is not important enough. It has been there for a long time now and Covid-19 has merely shone an uncompromising light on it. This frustration unchecked leads to that emotion I encountered in Nigeria as a boy: being amongst your people and somehow feeling not wanted.

Leaving this emotion to fester only leads to tragedy.