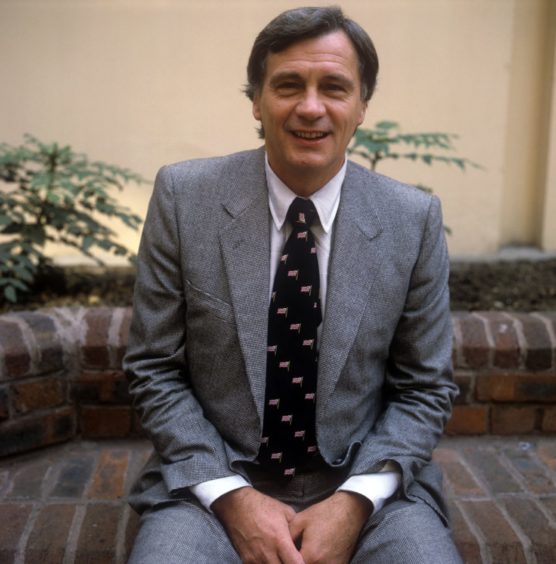

He wasn’t yet a knight on the Tyne. He wasn’t even a national treasure.

Bobby Robson was just a deeply unpopular manager of the England football team, whose players had been surgically undressed by the Soviet Union on their own Wembley pitch.

Football supporters south of the border had turned on a couple of head coaches before and they have turned on many more since but tens of thousands chanting ‘Robson out’ in unison (two different tunes, to not leave any room for doubt) at the end of a 1984 friendly won 2-0 by the visitors was peak 80s terrace disaffection.

Crude and cruel tabloid front pages with faces transposed on to root vegetables get talked about most when an era of Fleet Street self-righteous rage gets reflected upon but in Robson’s case, the fan reaction on the final whistle that day would have been far more impactive than anything the Murdoch and Maxwell red-tops could contrive.

That and the actual football he had just witnessed.

The John Motson BBC commentary of the match perfectly places it in its historic context.

The Iron Curtain was a few years away from corrosion setting in so eastern European professional footballers institutionally prevented from playing for clubs on the western side of the Cold War divide needed an introduction to armchair viewers.

“The defender is Baltacha,” said Motson early in the first half, albeit the pronunciation was more Latin American dance than elite Ukrainian athlete.

If the surnames were causing him a bit of a problem, the man with the microphone had no issue getting a handle on the glaring contrast in ability and strategy he had just put his voice to.

“It’s very difficult to make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear,” said Motson, giving England the mitigation of injury call-offs. “Especially when the Soviet Union bring players who were just too good for what England had available. England are still looking for shape and the way to the future.”

Beating Brazil in their next game bought Robson more time with the English public and his bosses at the Football Association. Then a respectable quarter-final World Cup exit in Mexico ’86, and the Hand of God what-might-have-beens, put enough credit in the bank to enable him to cling on to his job the other side of three games and three defeats at the Euro ’88 finals.

But in the build-up to Italia ’90 he knew there was a gulf needing to be bridged and the man who had made the USSR tick that uncomfortable summer afternoon at Wembley was the man he turned to for advice.

There have been plenty of compliments for Sergei Baltacha down the years but the great Sir Bobby Robson wanting to tap into his expertise would have to be pretty close to the top of the heap.

“We met in my home in Ipswich,” said Baltacha, who had not long before become the first Glasnost era Soviet player to sign for a club in Britain after transferring from Dynamo Kiev. “I just got a call from someone at the stadium to say: ‘Bobby Robson wants to meet you’.

“He wanted to know why we beat them all the time.

“He remembered the game at Wembley not long after he had been appointed England manager and then in 1988 we beat them easily at the European Championships again (Baltacha was a substitute on that occasion).

“He was preparing his team for the 1990 World Cup, his last tournament in charge, and wanted things to be different – he wanted to play with a sweeper. He asked if I could teach him about the position.

“I had to tell him that England was an easy game for us because of how they played, not because they had bad players, but because how they played.

“’Tell me more’, he said. ‘I’ll tell you how we played against you’, I said. ‘We knew the two weaknesses you would have. It didn’t matter who your central defenders were (it was Graham Roberts and Terry Fenwick at Wembley and Tony Adams and Dave Watson at the Euros). We knew they would be bigger than our ones but slower and not as good on the ball.

“They were no good with it. After five seconds the ball would be ours again. We knew it and we prepared for it.

They nearly won the World Cup so he would have been happy with my advice!

“Bobby wanted to change to a sweeper and asked me who I thought was suited to it. I said it should be the best player in your team – a player with brains, a guy who is a leader and can do a bit of everything, good at going forward when needed, good technically, good in the air and good tactically. He is the boss on the pitch. He dictates and does everything.

“I said: ‘It’s not for me to choose your player’ but he ended up picking Mark Wright. We didn’t speak afterwards but they nearly won the World Cup so he would have been happy with my advice!

“He was a great man. Not many managers at his level would say: ‘Look Sergei, I don’t really understand the sweeper position, can you help me?’

“I have met a lot of coaches afterwards but not many of them had his intelligence and humility – a quality man as a person and as a coach. It’s not easy to say to a player: ‘Can you teach me?’ Not many managers would do it. They think they know everything. That’s been my experience since then.

“I had problems with managers after that. They didn’t listen. All of the ones I fell out with was for that reason. I just wanted to help but none of them were like Bobby Robson and wanted to learn. You should always be willing to learn and admit you don’t know everything. Maybe they felt threatened. You have to listen and learn.”

Happily, Baltacha now finds himself getting the job satisfaction of elite young players seeking and absorbing the wisdom that some have inexplicably turned a deaf ear to. He is in his second spell working at Charlton Athletic’s youth academy, this time as technical coach.

“We have had some good players develop here in my nine years,” said the 62-year-old.

“I like to coach boys who have potential, the right attitude and desire. You can see if they have it straight away.”

Three players who have been guided by Baltacha stand out from the rest – Joe Gomez, Ademola Lookman and Ezri Konza.

As defenders, Liverpool’s Gomez and Aston Villa’s Konza will have picked up more from Baltacha in a positional sense than Lookman, a winger who has gone on to earn moves to Everton and RB Leipzig. But all had the common sense to realise that this was a man who should be listened to.

If it came to a game of ‘put your medals on the table’ or ‘so who did you play against?’ Baltacha would certainly earn instant respect. After winning the inaugural Under-20 World Cup in 1977, Baltacha was capped 45 times for the Soviet Union, had an Olympic bronze hung around his neck at the Moscow Games, clinched 11 domestic trophies and a European Cup Winners’ Cup in an outstanding Kiev team, played in the Spain ’82 World Cup and was part of the Soviet side defeated by the Netherlands in the ’88 Euro final.

“When I was the under-18 manager of Joe and Ademola they respected what I had achieved in my career for clubs and my country,” he said. “When I first saw Ademola I could see he was top class in everything – hard-working, willing to make sacrifices, strong character. It was the same with Joe and Ezri.

“When Joe and Ademola won the Under-20 World Cup, I was able to tell them I won the first one!

“Now I work with the younger age groups as well – seven, eight and nine-year-olds. They are interested in my career too. They’ll ask me: ‘Sergei, what was it like playing against Maradona?’ I say: ‘He was not bad but you can try to do better.’

“The older ones ask me about the van Basten goal. They ask me where I was when he scored it. I tell them not to mention it!”

Baltacha was still on the bench when one of the greatest goals of all time was scored, certainly the greatest goal in a major final. By the time he came on with just over 20 minutes to go, at 2-0 the game was all but over thanks to the back post volley that combined balletic agility, exquisite footballing technique and the fearless audacity of youth.

Maybe he tried to go for the middle of the goal and not the top corner!

“It was definitely one of the best goal I’ve ever seen,” he said. “There was a lot of luck as well but he deserved it because he tried it. Not many strikers would shoot from that angle. You can’t question the quality but maybe he tried to go for the middle of the goal and not the top corner!

“It changed the game. We had beaten them in the group stage 1-0. We had a couple of half-chances and missed a penalty but van Basten’s wasn’t even a half-chance, was it? Luck was on their side.

“It was a big disappointment. They were a young team, with stars coming through like van Basten, Gullit and Rijkard. Most of us were 30 or over. We had experience but they were fresher. We had beaten Italy in the semi-final and played really well. They still had a great team with Baresi and Maldini in it after winning the World Cup but against Holland it was not our day.”

That runners-up medal would turn out to be Baltacha’s last.

Ipswich Town were in no position to challenge for anything and you don’t sign for St Johnstone in the expectation of winning major trophies. But in striving to do that, raising standards around you, showing unparalleled defensive class and composure and immersing yourself in the local community, you can make sure you are never forgotten.

Legends are not always born out of longevity.

A recent Twitter fans’ poll saw Baltacha’s arm raised as Saints’ greatest ever foreign player. Social media might have passed him by but don’t think the vote escaped his attention – or that it didn’t fill him with immense pride.

After approaching 6,000 votes across the rounds, Sergei Baltacha crowned as the best foreign player to turn out for Saints. A deserved winner in a great contest. pic.twitter.com/7MmGfNFrCa

— St Johnstone 1884 (@stjohnstone1884) July 24, 2019

“I got a text message to tell me and it means a lot to me that the supporters think that way,” he said. “I love the club and the people.”

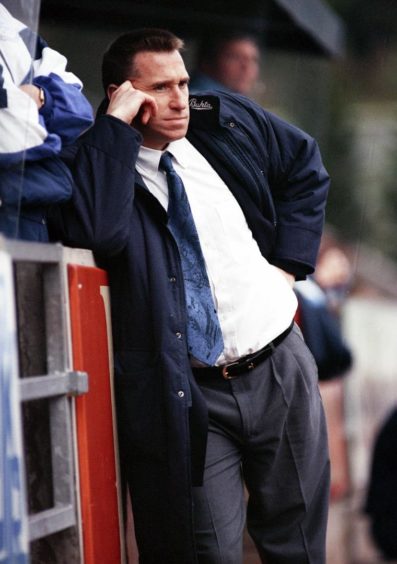

Legacy and folklore weren’t on Baltacha’s mind when he decided to cut short his stay in Suffolk. The targets was a good deal more modest – finding a club where he would get to play the style of football he had been reared on and in the position Bobby Robson had seen him excel in.

“I wasn’t happy at Ipswich,” he said. “My level had been playing at a World Cup, Olympic Games and European Championships. At Ipswich the manager John Duncan would say all the time: ‘Kick this bloody ball as far as you can’. He believed that playing passes was too risky. It was a different mentality.

“At Dynamo Kiev it was play, play, play. Ipswich was a good club and the people looked after me but I wasn’t happy at all from a football point of view.”

Saints manager Alex Totten was cut from a different cloth to Duncan. Perthshire boy Ian Redford, a team-mate of Baltacha’s at Portman Road, knew all about the cavalier adventure that had secured promotion to the Premier League and was happy to be the middle man who brought Baltacha and Geoff Brown together.

David Sheepshanks had stories of Russian vodka, the KGB, dimly-lit rooms and snow storms to tell after he secured Baltacha’s pioneering transfer to Ipswich a year and a bit earlier in Moscow. Brown’s task at the picture postcard edge of Highland Perthshire was somewhat less colourful and problematic.

Just play me as a sweeper was the long and the short of it.

Don’t worry, you will play sweeper, no question about this!

“Myself and Ian were friends as well as team-mates – our wives and our families,” Baltacha recalled.

“I told him that I was speaking to my agent about finding a club who played with a sweeper. I was playing right-back or central midfielder at Ipswich and I wasn’t enjoying it.

“He said there was a team had just been promoted to the Premier League in Scotland and that he knew the chairman and could talk to him.

“My agent was also looking at clubs in France. If I hadn’t found a club that wanted to play me in my position I would have gone back to Dynamo Kiev.

“I went to Perthshire and stayed in a hotel at Dunkeld and met Geoff. We talked and agreed the move. Alex wasn’t in the meeting and my first comment to Geoff was: ‘I have to play sweeper’. He said: ‘Don’t worry, you will play sweeper, no question about this!’”

The first season for Saints back in the top flight is cocooned in a golden glow of nostalgia alongside the one that preceded it. The core of the promotion team remained intact and got the upgrade it needed with the power and athleticism of John Inglis and the two-steps-ahead-of-the rest quality of his central defensive partner.

When you don’t score goals, don’t set them up, don’t beat a full-back with a drop of the shoulder, don’t fly into 40-60 tackles with reckless abandon and don’t play three stands of McDiarmid Park like a two-dollar fiddle at full-time, it really does take a special player to be elevated beyond others who did one or more of the above to great effect in the memories of supporters.

Positional excellence, unerring accuracy with diagonal passes that could never be mistaken for aimless punts and turning scalpel-sharp disruption of a threatening attack into an art form defined Baltacha.

From Gilhaus to Hateley, they all met their match. In the froth and the fury of the Scottish Premier League, Baltacha was invariably the man with the clearest head and the cleanest strip.

“I could see straight away there were good players at St Johnstone,” said Baltacha.

“Harry Curran, Mark Treanor, Roddy Grant, John Inglis and others. They were boys who wanted to play football and were allowed to. It was totally different to Ipswich.

“I tried to help the boys as well and they were happy to learn and listen. I really appreciated that, They would ask but I would tell them even if they didn’t!

“I was captain and a leader at Dynamo Kiev. They knew this. They were top class.

“After the first couple of games when we didn’t get good results we got better and better. We had good results against all the best teams.

“Before games I used to say to the boys: ‘Don’t worry about the result, worry about the performance’. If we’re playing well individually and collectively, we would win games. It was as simple as that.

“It’s what I still say now.

“Our under-13 team at Charlton lost 9-1 to Arsenal. They were down. I told them to forget about the result and just pass the ball and play football. Enjoy it. The coach was sick so I took the team for the next game against Crystal Palace. We performed well and beat Crystal Palace 5-2. It was fantastic. Everybody enjoyed it.

“That’s what it was like at St Johnstone in the first two seasons. We were a happy team – everybody was friends. It was a fantastic experience.”

“Fantastic” is not a description that could be applied to his third and last year at McDiarmid Park.

The passing of three decades hasn’t been as kind to John McClelland as it has to Baltacha. If the Northern Irishman is hoping for revisionist history of his time with Saints as player/coach then player/manager to be written, he’ll need to look for somebody else to pick up the pen.

He said at a supporters’ meeting that I wanted more money but that wasn’t true.

“After those first two years there were problems,” said Baltacha. “Alex didn’t listen. He brought John McClelland in and he didn’t even say hello to me on his first day at the club.

“I remembered him from the World Cup in Spain because he played for Northern Ireland but I didn’t know him. From that first meeting when he didn’t shake my hand I knew there would be a problem.

“After Alex was sacked John McClelland got his job. He said I was offered a new contract but the supporters didn’t know what was really going on. He said at a supporters’ meeting that I wanted more money but that wasn’t true.

“It was upsetting. I loved this club and could have played three or four more years there and maybe even taken a coaching or management job. It was sad for me to leave. I look back on my time with St Johnstone like I do with my time at Dynamo Kiev. I would have loved to have won a trophy for the supporters, who were fantastic.”

The closest that came to happening was a Scottish Cup run ended by Dundee United in a semi-final at East End Park.

“We could have won it that year,” said Baltacha. “We were the better team in that game and were unlucky.

”When St Johnstone beat Dundee United in the final in 2014 I was so glad they eventually did it. I watched it on the TV at home and I was so happy and proud for the club, the supporters and Geoff.

“A few of months ago I spoke to Geoff. I called him.

“With everything to do with my departure I didn’t feel right.

“He looked after me and my family. He is a good man and was a good chairman. He had good people working at the stadium.

“It was just that with all that happened with John McClelland, I felt there was a lot of confusion. I blame myself as well.

“I just felt like I needed to call Geoff. He was happy I phoned. We had a good talk about a lot of things. It’s better too late than never. Maybe it wasn’t the best end but I just wanted to say thank you.

“Our years in Perth were very happy times for all of us as family.”

That, of course, included watching daughter Elena develop as a tennis player. Sergei junior wasn’t too shabby with a racket in his hand either and it became a familiar sight from Viewlands Road to see brother and sister on opposite sides of the net on a hard court at Perth Academy.

Elena, who reached the heights of British number one before her tragic death six years ago, never lost her Scottish accent. Young Sergei still calls the country home and dad will do the same when he finishes with football.

“It’s like I have some Scottish blood,” he said. “My son still lives in Glasgow. He works in a bank and has two kids and a wife there.

“He has never wanted to leave. When he played for St Mirren there was a German club who wanted to sign him. I called him when he was over there to sign his contract. The weather was better and so was the money but he just wanted to come back to Scotland.

“I can understand why because it feels like I’m coming home when I go back there.

“When I retire I’ll definitely be going back to Scotland. But I’m not planning to retire yet.”

And there might even be one more Baltacha to find his way into professional sport.

“My youngest son Michael is now 16,” said Sergei. “He’s a good footballer. He’s six foot five. He could be a good central defender. We’ll see what happens.

“Michael wants to see the golf courses in Scotland more than anything. It’s not easy to play in London. He can hit the ball 250 metres but he’s never played proper golf.

“I want to show him Perth. I said to Geoff that we could come to a Saints game when we are up.

“I want to say thank you to the supporters.”

And they him, no doubt.