I had very nearly given up.

I’d been wandering along random forest tracks for what seemed like hours in the hunt for an elusive folly.

Convinced I’d never locate the thing, I sat down on a tree trunk, and attempted to look up old maps on my phone.

I’d parked my car in a layby on an unclassified road near one of various entrances to Panmure estate, and began walking in what Google Maps told me was the right direction.

I’d heard a great deal about the country estate, a few miles from Carnoustie, and had seen various atmospheric photos of its monuments on social media.

What can you discover on Panmure estate?

There’s the aforementioned folly, a commemorative column, the Panmure ‘testimonial’, a carved stone urn and an impressive three-arched bridge for starters.

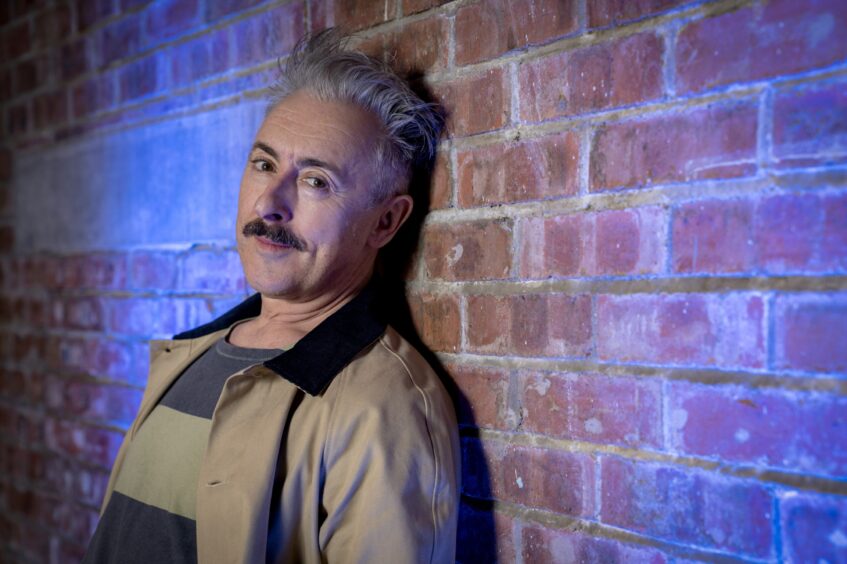

I was also aware that actor Alan Cumming grew up on the estate – his father was head forester, and the family lived at Nursery House, so called because it overlooked a tree nursery.

But the thing I was most excited about was this 18th Century folly.

I’d read that it was created to look like a ruined castle, and that it was now overgrown with trees and ivy. It looked to be the stuff of absolute fantasy.

Feeling defeated that I’d failed to find it, and feeling an uncomfortable rumble of hunger – I strolled forlornly down another tree-lined path.

And then, to my joy and wonder, it appeared out of nowhere!

How I found the folly

I practically hopped, skipped and jumped down the track towards it: I was so hungry I wanted to be sure I wasn’t hallucinating.

Assuming a ditch spanned by a drystane dyke had to be leaped across to reach the folly, I did just that.

But there’s actually a wee wooden bridge you can cross, and it’s safer to do so.

I then spent a happy half hour taking photos of the crumbling structure, gazing in awe at the intricate architecture, and imagining the estate’s families enjoying leisurely trips here of a Sunday.

There’s also a tower with a spiral staircase worthy of exploring right next to the castle.

Again, it was built as a folly, and never had a defensive role.

Both structures have been taken over by nature: ivy roots penetrate cracks and joints, and saplings sprout from walls.

The fact it’s not easy to find these hidden gems makes them all the more special. It was pure luck I pinned them down at at all.

What’s so special about Panmure estate?

Certainly, Panmure estate is an area of immense historic and archaeological importance.

No less than 13 of its monuments are listed with Historic Environment Scotland, and a number of archaeological areas of interest survive within the estate.

With none of them marked, it’s up to the explorer to use his or her wits to find them.

I was lucky to bump into a friendly local out walking his dog who was happy to share his insights and show me some of the estate’s treasures.

It’s thanks to this man – I’ll not mention his name – that I found myself in a magical wooded den, through which the Monikie Burn runs.

It’s a true walker’s paradise, and yet, we came across not another soul.

He also showed me cracking spots from which I could view the spectacular three-arched 19th Century Montague Bridge.

This feat of engineering allows the road to span an 80ft gully. I’d walked over it earlier and peered down into the abyss.

Another great find was one of two stone love seats, which boasts fantastic views down to the valley below.

What’s the story of Panmure House?

And then of course there’s the story of 17th Century Panmure House, the seat of the Earl of Panmure.

I knew vaguely of this already but my new friend pointed to the spot on which it once stood – now a modern home.

Regarded as one of the finest houses in Scotland, it was demolished in 1955 when it was considered to have deteriorated beyond repair.

The demolition was later described as “one of the greatest acts of officially-sanctioned vandalism of its type in Scotland”.

Why have gates been locked for 310 years?

Unlike the house, the impressive late 17th Century West Gates survive.

But the story goes that they have been locked since 1715, when James, the 4th Earl of Panmure, left to join the Jacobite uprising.

As he rode off, he gave orders that the gates were not to be opened until he returned, triumphant.

But he never did return. He was taken prisoner at the Battle of Sheriffmuir in 1715 before escaping to France and his estates were confiscated.

He died in exile in Paris in 1723.

What else is there to see?

There’s so much to discover around the estate – I’m well aware my evening of exploring was just the tip of the iceberg.

I did, however, also stumble upon the 18th Century Margaret’s Mount – an 8ft monument sitting on a raised artificial mound with a stone pedestal surmounted by a carved stone urn.

This is said to commemorate the parting of Earl James and Margaret following his escape after Sheriffmuir.

Also of interest is the 105ft high Panmure Testimonial, also known as the ‘Live and Let Live Memorial’.

This was erected in 1839 to commemorate the generosity of William Maule, the 2nd Earl of Panmure during the ‘year of short corn’ in 1826.

That was a year in which an unusually hot, dry summer led to severe food shortages.

In response, Lord Panmure suspended the collection of rent from his tenant farmers.

The 6ft tall red sandstone Camus Cross lies not too far away, sheltered in trees within the estate’s ground, and is thought to date from the 10th Century.

Also apparently worthy of exploration are the old gasworks that serviced Panmure House.

I’d run out of time so I’ll need to return soon to find this and other hidden pieces of history.

Conversation