At Blackness Road Fire Station in the warm heart of Dundee, a ceremony full of deserved pomp is in full swing.

Standard bearers, men of the cloth, a provost resplendent in his shining collar, and around 40 pairs of polished rubber boots crowd the engine garage.

After the piper plays his stirring song, a respectful hush falls over the gathering. A man steps up to the lectern. And then?

Sirens.

Throughout the room, unaccustomed fright mixes with knowing glances. Half of the boots shuffle out as men quietly excuse themselves; no fuss.

Moments later, when the speeches have resumed, the engine goes screaming down the road full of men, just here, off now to some terror unknown to the rest of us.

Business as usual. Coffee and sausage rolls at the reception.

It’s a stark reminder to those gathered of why we we are here; to honour two dedicated Dundonians who left the very same way, and never made it back.

Heroes Buist and Carnegie never forgotten

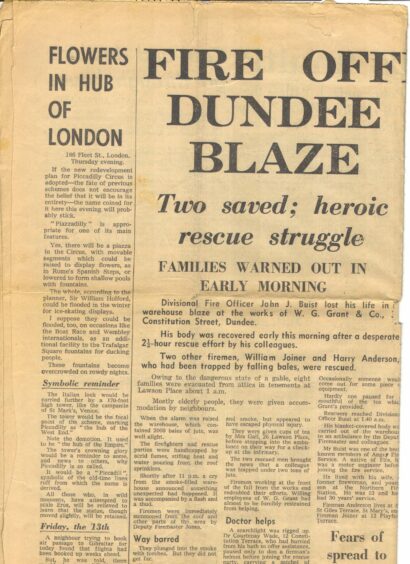

John Jamieson Buist and William Carnegie both gave their lives in the line of duty in separate Dundee fires in 1962.

John died aged 51 trying to aid his colleagues in a terrifying jute fire at Grants Jute Warehouse on April 13 1962.

Having first joined Dunfermline Fire Brigade as a driver in 1933, he worked all over Tayside and Fife during his 29-year career, and was survived by his wife and young son.

Fellow Dundonian William Carnegie died aged 44 after a 30ft fall from a faulty tenement window while fighting a house fire at 58 Mains Road.

Reports from the fire on June 14 1962 say he was climbing out of a dormer window to investigate damage to the roof when the frame gave way.

One witness, Robert Cunningham, told The Courier at the time: “His helmet came off as he fell. He didn’t even have time to shout.”

William, who spent time off-duty teaching disabled people in his community how to swim, died due to his severe head injuries on July 8. He left behind a wife and 17-year-old son.

And the Blackness Road station has now been marked with these men’s lasting memory, as two Red Plaques bearing the names of the heroes have been unveiled on the front of the building.

London’s Blue Plaques inspired scheme

“The Red Plaque scheme was born out of seeing the blue plaques in London, for famous people that have been born or lived in certain areas,” explains Simon Leroux, north area secretary for the Fire Brigade Union.

“We thought there should be a similar scheme for real heroes. Why not commemorate our brothers and sisters that have fallen in the line of duty, doing a job that we all could potentially give our lives for?”

Since 2017, the scheme – which is entirely funded by the FBU’s Firefighters 100 public lottery – has honoured more than 60 fallen heroes across the UK.

The latest two, William Carnegie and John Buist, passed away 61 years ago, but it’s clear their loss is still keenly felt by those left behind.

Bell Street station was home to Buist family

John’s son Ron Buist, who was still a young boy when his dad died, fondly recalls growing up in the heart of his father’s vocation.

“I have vague memories of Bell Street,” he reveals. “A bunker in the kitchen where I tried my Peter Pan flying impersonation. It was not a success, bloody nose, blood and snot all over the place!

“I remember the control room that had, to me, the best hand painted map of Dundee. With little red lights for the various stations, Bell Street, the North and Brown Street Broughty Ferry. These were illuminated when appliances were deployed.

“The cobbles outside the front of the station were wooden,” he adds, “from the days of horse drawn appliances.”

John’s wife (Ron’s mother) Williamina ‘Mina’ Buist also played a part in the fire service as a telephonist in the Angus Area Fire Brigade.

They were a family living in a flat above a control room, their whole lives defined by their dedication to the cause; and Ron and Mina’s lives were irrevocably changed the day their beloved John didn’t come back.

“The dangers they faced 60 years ago are different from the ones faced by today’s firefighters,” reflects Ron in a moving tribute. “But each and every time they are called to an incident they do not know what they will face.

“To some he was John, to others Jack, or Jock; to others he was ‘sir’. But to me he will always be Dad.”

‘Grants was my first jute fire’

The sacrifice made by firefighters who give their lives to save those of others can only be matched in generosity by that of their families, who watch their loved ones leave to face possible death with every single call-out.

For many ordinary folk, such a high risk job would be a source of anxiety; but for former firefighter John McRae, it’s a point of familial pride.

“Let me tell you something,” he begins, his eyes twinkling. “My son was in the brigade, my brother was in the brigade, and my son-in-law was in the brigade. And so was I, for 30 years.”

John was part of the team who attended the Grants Jute Warehouse fire which killed John Buist. It was the first “big” fire of his career, and despite its tragic consequences, he remained undeterred from his dangerous work.

Brave survivor tells story of ‘nightmare’ blaze

“This one at Grants was my first jute fire as a laddie, and it was quite hairy, I can assure you!” John recalls wryly. “I was only six months in the job!”

“Two of our fireman were wearing breathing apparatus (BA), and they went in to check the strength of the fire at the rear of the shed.

“The east side was a solid wall of corrugated iron, and we were detailed to go round that and take off the iron sheets and get a line of hose in to fight the fire at the rear.

“The two lads, Harry (Anderson) and Wullie (Joiner) that had been in checking it out lost their guideline, because the bales expanded and the bail ties burst, and the whole thing had come apart.

“That’s what killed John Buist, a half bale falling on top of him,” John says quietly. “We didn’t know.

“Harry and Wullie went to check the spread of the fire at the rear,” he continues. “We didn’t know these two lads were trapped.

“We took off the corrugated iron sheets and we heard the BA warning whistles, which go off when there’s ten minutes of oxygen left.

“When went into the shed, it was all smoke and flames, and got the two of them out. The first thing they said was: ‘Where have you been?!’

“We checked them to see if they were alright and they were, but they were bloomin’ lucky.

“It was a nightmare.”

Firefighters trained to keep ‘calm souch’

But in spite of the terrifying, traumatic conditions he witnessed in that fire, John reveals he “can’t ever remember feeling scared”.

“The training you get from the fire brigade doesn’t really allow you to be scared,” he muses. “It allows you to be damn careful!

“But I can’t recall any crew I was on ever being in a panic, and I think you’ve got to hand it to the training – it teaches you to keep a ‘calm souch’!”

It’s a sentiment echoed by current senior officer for Perth, Kinross, Angus and Dundee, Jason Sharp.

To him, education and training are the key to survival, and he is striving to keep standards high for the communities he serves.

“No matter if it’s now or 61 years ago, the fundamentals of fire remain the same,” he states matter-of-factly.

“The Red Plaques remind us of the real risks that our firefighters take on a daily basis when they’re protecting the communities of Dundee.

“We dedicate a lot of our time to practicing for events like that, so we’re rehearsing how to put fires out so that we can retain our safety.

“We also listen to experienced firefighters on our watches who tell us the stories of previous incidents, so we learn from other people’s attendance of fires as well.”

‘It’s a bit of a calling’

The drills may be pretend, but the risk – and the bravery needed to face it – is very real, something that the shining new Red Plaques on the side of Blackness Fire Station stand to remind each of those who leave on their bright engines.

So why do it? Why pick a profession so uniquely dangerous, with accidents, flames, and hidden carcinogens all but guaranteed?

“It sounds cliché but it’s a bit of a calling,” admits FBU’s Simon, who is also a crew commander in Aberdeen.

“I think you have to be the right kind of person to want to do this job. You want to help people, and what better way than in their most desperate hour? To have that ability to go and either save somebody’s life or property, or pets, and create a bond with that individual.

“Because they’ll never forget that. It’s probably the worst day of their life – and we can turn up and try to make a difference.”

To find out more about the Red Plaque scheme, enter the Firefighters 100 lottery, or share a memory of John or William alongside their plaque stories, please visit the Red Plaque website.

Conversation